No Master Territories: Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image is dedicated to works of nonfiction that invent new languages for the representation of gendered experience. Concentrating on the period of the 1970s to 1990s, a time when women’s liberation movements took hold internationally, it responds to the contemporary imperative to recover the breadth of women’s contributions to film history in a global context.

Drawing its title from the work of Trinh T. Minh-ha, the programme focuses on the areas of moving image practice that have been the most inhabited by women, yet which are frequently pushed to the sidelines of film histories, feminist ones included: the overlapping and diverging traditions of documentary and experimental film. Emanating from diverse geopolitical contexts, these works conform to no single aesthetic or political stance. Many were conceived in intimate relation to feminist activism, which has long recognised the importance of visual media as a means of domination and emancipation; others exist at a distance from any organized social movement. The programme celebrates the heterogeneity of feminist nonfiction, generating a fragmentary atlas that maps divergent positionalities.

Curated by Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg, No Master Territories originated as a gallery exhibition and film programme of over 100 works by 89 individuals and collectives, on view at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, in summer 2022.

No Master Territories

By Erika Balsom

No Master Territories: Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image is dedicated to works of non-fiction that seek to invent new audiovisual languages for the representation of gendered experience. Concentrating on the period of the 1970s to 1990s, a time when women’s liberation movements took hold internationally, it pays homage to the important work of the past and responds to the urgencies of today. At a time when feminism is enjoying a mainstream resurgence yet figures as a more contradictory and slippery signifier than perhaps ever before, the programme makes a strategic return, exploring how filmmakers of previous generations have confronted issues including work, the body, mass media, exile, family, racism, and settler colonialism. As the outcome of research conducted in dialogue with collaborators from around the world, the project aims to enlarge available histories by tracing multiple genealogies that circumvent the impasses of contemporary neoliberal feminisms.

The programme focuses on those areas of moving image practice that have been the most inhabited by women and the most engaged in an oppositional reformulation of all aspects of the cinematic institution, yet which are frequently pushed to the sidelines of film histories, feminist ones included: the overlapping and diverging traditions of documentary and experimental film and video. One might assume that women are relatively absent from film history because they were absent from filmmaking – when this is emphatically not the case, if one casts a wider net. Look only at Hollywood and the relative lack of women will be true; look at the international art cinema, or at 35mm production more generally, and it will still largely hold. But look at the domain of nonfiction – which necessarily entails revising criteria of what counts as “quality” and what makes a film important – and an abundance of compelling practices rush to the fore. As film scholar Teresa Castro has put it, “Uncredited, undocumented, and so often confronted with ‘failures’ that sent them to the ash heap of history, women – and, as a matter of course, very different women – were there all along.”

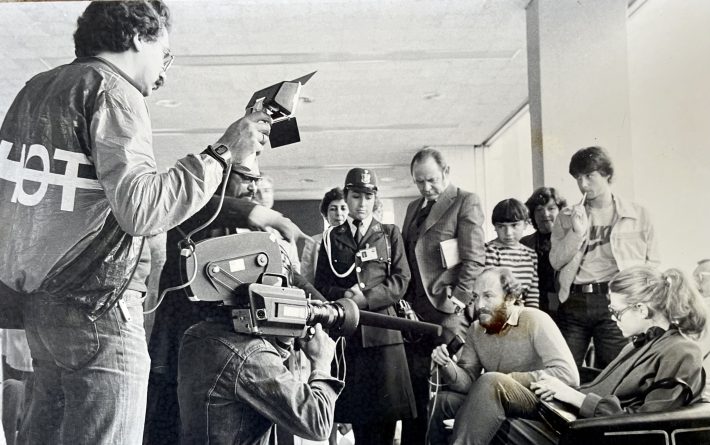

Women were there, their work was there, in non-professional formats, supported by alternative infrastructures. Produced in diverse geopolitical contexts, the films included in this programme emanate from such milieux, espousing working methods very different to those of the industry and historically circulating within non-commercial, sometimes nontheatrical, networks of exhibition. They adopt strategies that range from avant-garde experimentation to essay filmmaking, from docufiction to first-person reflection and on-the-ground interviews. Many are conceived in intimate relation to feminist activism, which has long recognized the importance of visual media as a means of domination and emancipation; others exist at a distance from any organized social movement; and some are made by women who do not self-identify as feminist but whose work nonetheless resonates with feminist concerns.

Just as the films adopt no single aesthetic style, so too do they conform to no single political stance. Rather than prescribing what feminist filmmaking or feminism itself is or should be, the programme seeks to create what the cultural theorist Ella Shohat has called a “plurilogue” between diverse resistant practices, one that “emphasizes not simply the range of culturally distinct gendered and sexualized subjects, but also the contradictions within this range, always in hope of forging alternative epistemologies and imaginative alliances.”

The title No Master Territories is itself an archival return, borrowed from a section heading in Trinh T. Minh-ha’s 1991 essay collection When the Moon Waxes Red: Representation, Gender and Cultural Politics. It is an abolitionist declaration, profoundly utopian, that speaks to the need for a bold reimagining of the world which would put an end to domination in all its forms, not only those related to gender. Gesturing to a feminist agenda that is irreducible to single-issue politics, the phrase deploys a geographical image, one freighted with the legacies of slavery and colonialism, to imagine a material and epistemological condition free from the tyranny of totalizing control and possession. It rejects the ideology of the artistic “masterpiece”, along with the romantic concept of the creative subject that accompanies it, and instead emphasizes cross-disciplinary pollinations. Unravelling the imperial partition of centre and periphery, ruler and ruled, it opens a fluid space in which non-hierarchical, transversal, and perhaps unexpected connections can occur.

A world with no master territories would look nothing like the one that exists at present. It is perhaps an impossibility. Nonetheless, this demand has a propulsive, generative force, registering a dissociation from punishing norms, sparking dreams of radical reinvention. These films take up this wager, rejecting the authority of received frameworks of intelligibility. They embrace the moving image as a wellspring of feminist imagination – a way of not only relating to the world but remaking it.

N.B.

On terminology: The term “woman” is employed here in a maximally inclusive sense, encompassing all those who identify as such, regardless of the gender to which they were assigned at birth. As feminist writer and organizer Lola Olufemi has put it, “woman” is “a strategic coalition, an umbrella under which we gather in order to make political demands… In a liberated future, it might not exist at all.”