Rooted in the social and political struggles of the women’s liberation movement in the 1970s, this programme of feminist films made between 1985-1991 journeys through the lives of women who challenged traditional patriarchal structures in India. The complexities of women’s invisible labour as reproductive machines, sexual objects, home makers, and keepers of tradition, morality and cultural history are made starkly visible. By highlighting the interconnectedness of the individual and social self, these films offer an encounter with diverse forms of feminisms. Personal liberation is embedded in collective liberation.

While Deepa Dhanraj’s Something Like A War and Nilita Vachani’s Eyes of Stone portray how a woman’s body is used as a site for both social control and resistance, Reena Mohan’s Kamlabai and Mira Nair’s India Cabaret construct intimate portraits of female subjectivity and transgression. As the filmmakers grapple with their own class and caste privileges, these powerful, moving, and often disturbing ethnographies are extraordinary documents of early feminist filmmaking practices in India.

The Invisible Self is curated by Shai Heredia, founding director of Experimenta India.

Age of Aquarius

By Arshia Sattar

I watched these films and others like them in India in the moment when they were made – I watched them in leaky college classrooms with windows that let in the grey monsoon light because the panes, grimy with dust and pigeon shit, had been papered over too quickly for the screening, where the sound system crackled and spat over the insistent whirr of the 16mm projector, where none of this mattered because simply being there was a political act of solidarity and revolution. Sometimes, we watched in trade union halls where there would be the luxury of folding chairs and tepid cups of tea. Or at a youth festival where the screening was outdoors and we had to brave mosquitoes and other things that bite in the night. Later, we watched on wretched, overplayed video tapes in the homes of friends of friends where we sat on the floor and made sure to tidy up the cushions and rugs and tumblers sticky with sweet, fruity drinks before we left. Not all the screenings were clandestine but we always heard about them through grapevines and via jungle drums, from each other, from hand drawn posters and hasty public announcements.

The 1970s were a decade of turbulence and change in India. Twenty-five years after Independence, the dreams and promises of a new nation were in tatters. Workers, peasants, students, women were all in the streets, protesting, calling for change, challenging the status quo. In 1975, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared the Emergency and suspended the Constitution, throwing thousands into jail and unleashing social policies (such as forced sterilisations for population control) that were positively demonic. I was an 18-year-old girl in Bombay (now Mumbai) at the end of that decade, at a college known by then for its radical student politics. Like so many others, I had become restless in my sheltered middle-class life, I was sure there was more in the world that I needed to know and be. Even in our homes, women’s conversations changed from recipes and sewing patterns to rights and justice. The Emergency had politicised everyone, it seemed, and the women’s movement, galvanised by the custodial rape of a teenage girl in 1972, had a name and a face – Mathura – at its centre. For so many of us, protesting with women for women was less intimidating, easier, somehow, closer to ourselves. But as the women’s movement rapidly grew larger and more inclusive of people and issues, these became our own first steps towards a wider and deeper political involvement.

I saw more documentary films in those days before theatrical releases and formal distribution than I see now when they are but one small subscription away from me. Back then, we were a tribe, we were part of a community of shared beliefs and hopes. Often, the films and the gatherings they generated functioned as sources of news and information – we learned about atrocities against women in villages far away from us, about peasant resistance, about the murders and assassinations of people’s leaders, about villages erased by development, about justice undone and injustice done. We saw what the media did not show us, we heard voices that had been silenced in a national conversation, we listened to songs in other languages that told us stories we had never known. Every film was immediate, every conversation that came out of it was urgent.

We gathered not just to watch a film, we came together to participate in a movement. In two movements, perhaps – one political and the other artistic. The growing demands for women’s rights and the flowering of documentary film happened almost simultaneously in India. Both uprisings, in art and in politics, were led by women. Each supported the other, both were dynamic, volatile, beautiful and profoundly significant. The women who led these parallel movements were shining and unafraid. They treated sisterhood as the most important value – across caste, class, religion, location, profession, habit, sexual preference. They made films about their politics, the ideologies we encountered in their words and pictures supplied the fuel for marches and sit-ins and slogans and posters.

Perhaps that was the Age of Aquarius, perhaps we were all stardust, then. But what does it mean, for someone of my generation and with my ideological positions to watch these films now, more than thirty years after they were made, three decades after I was the young woman who was roused to a feminist political consciousness by what I saw and heard at the time?

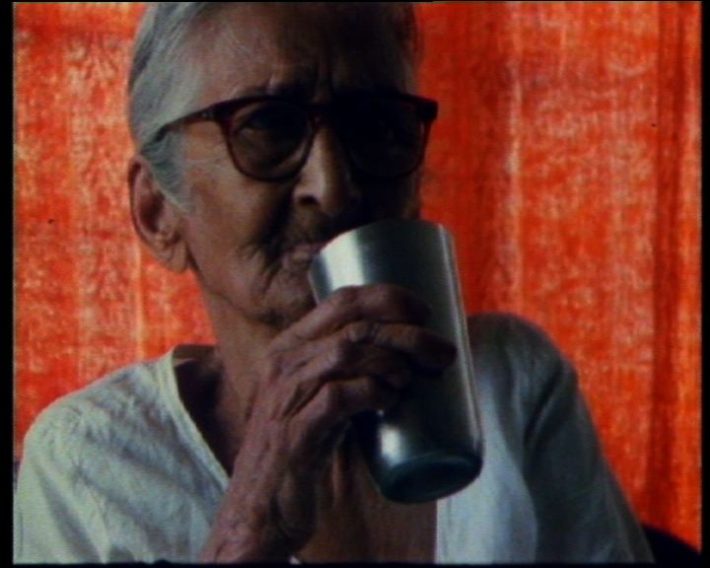

These films are testaments of their time and place, profoundly particular but also, powerfully universal. They are set against an active, vicious (but hardly unique or archaic) patriarchy and I remain stunned by the cruelty and systemic debasement of women that these four films bring to our attention – no matter that the saucy elderly female actor, Kamala, dances lithely and triumphantly at the end of Reena Mohan’s Kamlabai, no matter that one of the dancers in Mira Nair’s India Cabaret collects her earnings and goes off to marry a customer who has promised her dignity and self-respect. I remain sick to my stomach when Shanta is literally dis-possessed of the goddess in Nilita Vachani’s Eyes of Stone and returns to household drudgery for a man who plans to get another woman because he does not like Shanta’s cooking. Or when village women are introduced to a conversation about their bodies and sexual pleasure in Deepa Dhanraj’s Something Like a War while their sisters are lined up like cattle in an abattoir to feed a brutal Family Planning program. I am still shaken to the core of my being by the men in these films – the callous husband, the cavalier gynaecologist, the rapacious agent, the complacent family man.

I look around and I see that little has changed. But when I look around, I also know that we cannot watch these films as ethnographies from a distant and barbaric culture trapped in its own past. We cannot walk out of the screening saying “well, you know, that happens in India… or in Kenya, or in Iran.” We cannot let the extreme behaviours of that patriarchy blind us to what we live with, in our own here and now.

Watching these films in the present reminds us that the fight continues, for the battle has not been won. It may never be won. But every act of resistance, every finger raised in defiance, every film watched, every solidarity reached across gender, caste, class, race, religion and culture, every community formed, however tentative, will add to our strength. It will empower our daughters and in the best of times, it will persuade our sons that the world does not belong to them alone.

Arshia Sattar works with myth, epic and the classical story traditions of the Indian sub-continent. She writes and teaches about Indian literatures at home and abroad and has recently started retelling classical stories for younger readers. She is the co-Founder and co-Director of Sangam House, an international writers’ residency based in Bangalore, India.