In Focus: Renate Sami

As Ute Aurand writes, “Since her first film in 1975, each and every one of her works has emerged from the same strong desire to make this particular film. Whether long or short films, shot on 16 mm, Mini DV or HD, without sound or without dialogue or music – what they all have in common is the special inner freedom with which Renate Sami gives every film its form.”

Sami was moved into becoming a filmmaker aged forty following the death of Holger Meins, the subject of her first film. Later subjects include the work of writers and painters, her films proposing an imaginary dialogue with those of fellow filmmakers such as Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Harun Farocki and Ute Aurand, with whom Sami co-founded “FilmSamstag” (Film Saturday), a monthly film programme at Kino Filmkunsthaus Babylon Mitte that ran from 1997 to 2007. This In Focus programme is the first survey of her work in the UK.

In collaboration with the Goethe-Institut and with thanks to the Deutsche Kinemathek

Renate Sami 1

Thu 9th September, 18.30

Goethe-Institut

From the Cloud to the Resistance

Friday 10th September, 18.15

Ciné Lumière – Institut français

Renate Sami 2

Fri 10th September, 20.30

Goethe-Institut

Renate Sami 3

Sat 11th September, 14.00

Goethe-Institut

Renate Sami 4

Sun 12th September, 13.30

Goethe-Institut

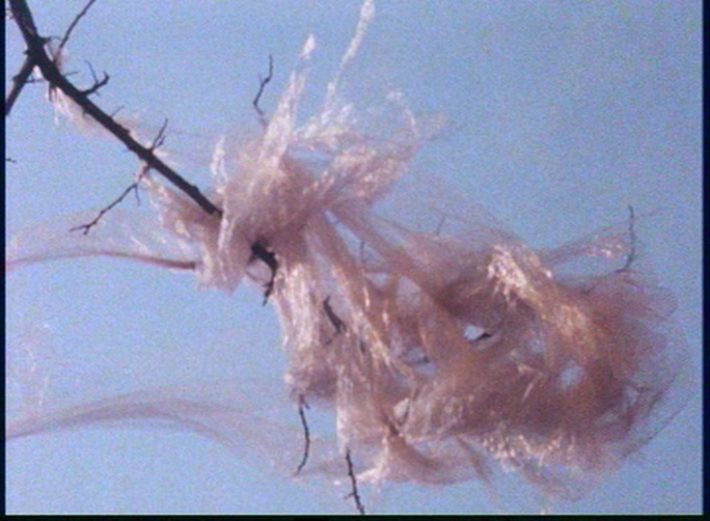

when you see a rose (wenn du eine rose siehst) – courtesy Renate Sami

A Beginning

by Renate Sami

I had my first direct contact with film in 1969 when I moved into a shared apartment with two film students: Ulrike Edschmid and Philip (Werner) Sauber. I was working as a teacher and translator. The student movement was in full swing and when I think back to that time today, it is a big clutter of people and experiences, demonstrations, teach-ins, and Kommune 1 happenings. I think of slogans, movie titles, sayings: “Create two, three, many Vietnams” from Che Guevara, who had been killed a year earlier, Mao Tse Tung’s “A revolution is not doing embroidery,” Bob Dylan’s “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows,” Godard’s Weekend, La Chinoise, and One Plus One with the Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil.”

Back then, the apartment on Grunewaldstrasse was always full of people constantly coming and going. Sometimes someone spent the night or came in the middle of the night and disappeared again the next morning, or stayed for weeks, like Holger Meins, who was particularly fond of the Straubs’ films. At the time, Holger had just finished Oskar Langenfeld, which the Straubs must have really liked because when he died, they added the dedication “For Holger Meins” to their film Moses and Aaron. Philip Sauber had also just completed his film Der einsame Wanderer (The Lonely Wanderer) and both he and Holger were expelled with a group of other students because they had occupied the offices of the film school’s director. The cause was that, on the instructions of the Senator of the Interior, Günter Peter Straschek’s film Ein Western für den SDS (A Western for the SDS) had not been approved. Our kitchen became a centre for discussions about how things should proceed. Harun Farocki lived two floors up, Hartmut Bitomsky was often around, and everyone was making small films that were shown at the teach-ins and student gatherings like anti-newsreels.

We would often go to the movies and talked a lot about films. Bresson, Godard, Rossellini, the Straubs, Renoir, and Buñuel, but also Sergio Corbucci’s Il Mercenario (The Mercenary), which deals with the resistance of Mexican miners, were studied and discussed. Films were supposed to be enlightening and the form was important too. New wine shouldn’t fill old wineskins. A big surprise was Straub and Huillet’s Chronik der Anna Magdalena Bach (Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach). A year after Nicht versöhnt oder Es hilft nur Gewalt, wo Gewalt herrscht (Not Reconciled or Only Violence Helps Where Violence Rules), at the end of which an old woman shoots at a Nazi, they were presenting a film in which the main thing to watch was musicians at work. Bach’s music, a few scenes from his life, places where he had been employed, some pieces of handwriting, notes, and people playing music again and again.

Holger had shot a small film showing how to make a Molotov cocktail. The police were looking for him and shortly thereafter he disappeared in the underground. Soon after that Philip said goodbye to me and disappeared too. One year later, Holger was arrested along with Andreas Baader and Jan Carl Raspe and died during a hunger strike in prison in 1974. Philip died a year later during a shoot-out with the police. There is a book about him by Ulrike Edschmid, Das Verschwinden des Philip S. (The Disappearance of Philip S.). And with the film Es stirbt allerdings ein jeder, Frage ist nur wie und wie du gelebt hast. Holger Meins (We All Die, The Main Thing However is How and How We Live our Lives. Holger Meins), I became a filmmaker.

(Translated by Ted Fendt)