Truant

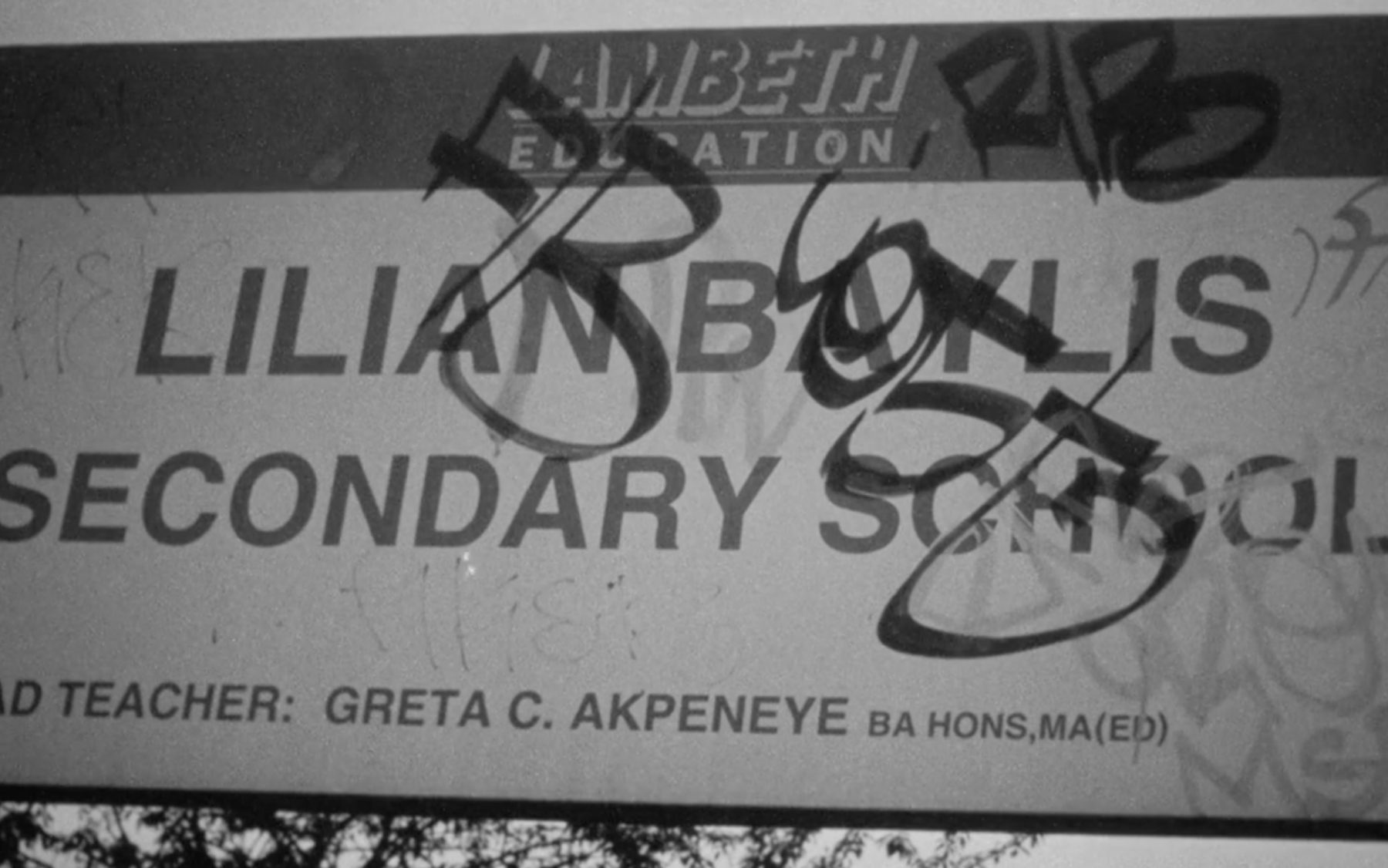

Surviving You, Always (Morgan Quantaince, 2020).

Today, a day that I’m off school because I have let myself back into the house after everyone has left, I’m going upstairs to my brother’s room, and I’m going because there’s nothing on England’s four terrestrial TV channels in the ‘daytime.’ Alongside one wall there are boxes and boxes of films in the VHS format stacked in neat rows to my waist. They are mostly official copies, but some are not. Some are in black boxes. They are pirated or banned.

I have seen many of these films before. They include such titles as: A Clockwork Orange, Killing Zoe, The Devils, Man Bites Dog, The Last Emperor, I Spit on Your Grave, Henry: Portrait of A Serial Killer, Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence, Cannibal Ferox, or Short Cuts. These days, I’ve been watching Hong Kong action films in his collection. I like a director called John Woo and an actor called Chow Yun Fat.

‘Quentin Tarantino ripped this off for Reservoir Dogs,’ my brother told me when we watched a film together called City on Fire, directed by Ringo Lam in 1987. He said the same thing again when we watched A Better Tomorrow II, directed by John Woo, also in 1987. He said the same thing to me again when we watched The Taking of the Pelham One Two Three, an American film, directed by Joseph Sargeant in 1974. He would explain in more detail. ‘This is where Tarantino got the thing with the suits,’ he’d say, or ‘Tarantino got the plot from this,’ or ‘see, this is where Tarantino got the idea for using colours for names,’ and I would say ‘yeah’ because I understood and I could see that he was right, and this must be how everybody does it, and it felt good because I was being taught something by my big brother and we, or rather he, rarely talked anymore.

‘A ballet of violence’ is how some article described John Woo’s fight choreography. I liked the phrase and thought I could use it if anyone asked me what I thought about his directorial style. ‘He makes a ballet of violence’ is what I would say if they asked, and I imagined that I’d sound both sophisticated and sensitive.

My favourite John Woo film was Hard Boiled, released in 1992. The opening sequence was extraordinary. In it, Chow Yun-Fat, who is playing a cop, kills many people by shooting them to death in a restaurant dive. For some reason the dive is filled with small bird cages hanging all over the place. They each contain a tiny tweeting bird. Chow’s character also has a bird cage, but he has two guns hidden inside. The guns are revealed when he stamps on the cage and they fall out of the shattered base, in slow motion.

In the final sequence, Chow shoots a triad at point blank range, but you don’t see the triad die. The camera remains in a tight close up on Chow’s face, which is powdered white because he is now in the basement of the restaurant, and the white powder is really flour used for making dumplings, and the flour has exploded all over the place due to stray bullets. The camera remains on Chow’s face after the bullet blasts the triad’s brains all over it, and there is a dramatic contrast between the red blood and the white powder.

Although I’m now scanning the column of VHS cassettes in which Woo’s films are stacked, I’ve seen them all. So, I pull out another tape and the title on the side of the box is ‘Farewell My Concubine’, directed by Chen Kaige in 1993.

Downstairs in the living room, I’m sitting on our sofa, about two and a half meters from the small, possibly 18-inch, colour television that we have in one corner. Farewell My Concubine is a dramatic historical epic about the tragic fate of two male friends. They are both orphans who have grown up in a brutal opera school and go on to become stars of the Peking opera in adulthood. The historic sweep of the film takes in the cultural revolution and its modern aftermath. Around the complicated lives of the two male leads swirl currents of betrayal, queer masculinity, gender confusion, abuse, jealousy, love, obsession and death. It is a world that is shockingly different to my own, but I am spellbound by it and by the trio of actors that make up its main cast: Leslie Cheung, Zhang Fengyi and Gong Li.

I identify with the beatings that the two male characters suffer as children in the opera school, because who among us has not suffered beatings, who among us has not also suffered through a tyrannical education system, who among us isn’t a thief, a liar, or a ‘disruptive element’ in school, who among us doesn’t wish he could do backflips or the splits or smash bricks against his forehead or command an audience.

This scene from the film haunts me: the ‘effeminate’ orphan boy who will grow into one of the film’s two main characters is brought to the opera school by his prostitute mother. He has six fingers on one hand and is rejected. His mother takes him to an alley. She blindfolds him. ‘Ma. My hands are freezing,’ he says ‘they feel like ice.’ She holds him still and chops off his extra finger. Throughout, the song of a local tradesman echoes between the houses. ‘Sharpen your knives,’ he calls out in Mandarin.

In the evening I sing the knife sharpener’s song under my breath as I walk to Clapham Common. It is a cold winter night, and my hands are freezing. On the bench in front of a small forest that is apparently a queer cruising spot, I hum the song. I am sitting with four ‘friends’, two of whom will, a year or so later, beat a man unconscious in the forest for being gay and laugh about how his nose was broken and how his face was bleeding and how they ‘knocked him out’, and I will feel sick and conflicted to hear this, because my uncle is gay and there is nothing wrong with homosexuality. I will feel sick and conflicted because beating people for who they sleep with is wrong, and because I will do nothing about it in that present and because I can do nothing to stop it in the past, and because I am something like a coward and ‘if there’s one thing a man should not be it is a coward.’

‘Sharpen your knives,’ it echoes in my head while we sit there in silence because we have smoked too much weed, and we are stoned mute. ‘Sharpen your knives,’ it’s there again when a boy, whose company we bear without protest or sarcasm because he is stronger, rides over to us on a mountain bike he stole from someone and asks if ‘Elizabeth sucks dick.’ ‘Sharpen your knives,’ Elizabeth is walking away from us later with the boy. ‘Sharpen your knives,’ I am walking home past houses I will never be able to afford, and it is late and quiet, and the streets are still and empty, and everything is dark or else yellow dark from the streetlights. ‘Sharpen your knives’ I am in my room, standing at the window which has a horizontal bar across it for some reason. ‘Sharpen your knives.’

Years after the first time I watched Farewell My Concubine, I’m in central London, in the Prince Charles cinema with my friend Heeyeon Park. We are watching the end credits roll for Days of Being Wild, directed by Wong Kar Wai in 1997. ‘What did you think?’, I ask, but she is looking at the screen. She says without turning to face me, ‘I’m going to watch to the end. You can wait for me outside, if you like.’ I’m confused by the coldness of her response. What have I done to make her think I would walk out? What previous ‘friend’ was too impatient and insensitive to wait?

Later, as we are walking across Waterloo bridge towards the Southbank Heeyeon says, ‘I don’t think it’s easy to convey just how important the actors in that film were to people in Korea, my generation, culturally speaking.’

I say ‘Who, you mean Leslie Cheung?’

‘Him and everyone.’ says Heeyeon ‘I mean they were as important and as big for a younger audience as say Leonardo DiCaprio was here.’

‘I think Leslie Cheung is a brilliant actor,’ I say ‘I almost didn’t recognise him in this film at first. I know him best from Farewell My Concubine.’

Heeyeon says ‘I love that film.’

I say ‘me too.’

The song of the knife sharpener echoes in my mind and I am back walking home on that evening years ago, stoned and without prospects. I am back, hearing about the violence that I could not stop and I did not condemn, and I am thinking of being a coward again and I know it is a feeling that I will never escape and so I open my mouth to talk about something other than what I am.

I tell Heeyeon that I was fascinated by the sounds of Mandarin, and how I would try to mimic the way that the characters spoke in the film, how certain words and phrases stuck in my mind (‘sharpen your knives’) and how if I could have, I would have learned Mandarin when I was younger.

‘Still,’ I say ‘that film really expanded my horizons. I mean it introduced me to a place, a history, an aesthetic and a way of being that I never knew existed.’

Heeyeon says, ‘that’s so interesting to hear you say that about Mandarin. It’s exactly what I did with English.’

We are in the BFI bar, sitting and talking about films that have influenced us. I have been here before. Years ago, when it was the National Film Theatre. I worked in the bookshop and read all of the stock, and years before that, before I was born, my mum worked here as an usher too. ‘You know’ I say ‘I think one of the most important films that I have ever seen, one of the most influential anyway, was The Scent of Green Papaya.‘

Directed by Tran Anh Hung in 1993, The Scent of Green Papaya tells the story of Mui, a young servant girl who grows into a woman through the course of the film. The first time I saw it was late night on television. I had never seen anything like it. The colours, the stillness, I never knew or understood that beauty could be so austere and so mysterious.

Tran Anh Hung taught me so much about form, about how, beyond the territory of the familiar, lies a zone of sensory and psychological experiences that are challenging and entirely new. Everything seemed somehow changed after I saw The Scent of Green Papaya for the first time. I became interested in silence as much as I was interested in sound. Yes, the intimate interiority of the Vietnam depicted in the film was a world away from the concrete reality of my council estate, the noise of London, and the violence that seemed to be around every corner and behind every interaction, but still my gaze sought out elements within the metropolis that could satisfy my newfound appetite for an uncanny experience of beauty. I was a different person, and somehow this was linked to the fact that I now knew beauty could also be uncanny, and that beauty could also disturb.

I’m walking home alone after hugging Heeyeon goodbye. The evening is cool, but not cold and so I don’t mind taking the long route along the river Thames. I want to hear the soundtrack from The Scent of Green Papaya and so I take out my smartphone, type in the composer’s name, which is Thôn Thât Thiêt, and press play. I’m surprised that the first piece of music is a rendition of Debussy’s Claire de lune and I am suddenly shaken by the softness of this recording, and I am shaken by the force of this recording, and I am shaken by the emotions and memories that well up inside of me. I stop. I am by the water, which is black and blue and reflective because it is dark, and I remember how we spread the ashes of my friend here who committed suicide, and his mother was with us, and I still don’t know why he did it, but when we spoke about him after the ashes drifted away or sunk, waves appeared in the water, and we all looked at each other and said, ‘Ben is here’ and smiled. I am looking out into the black water and the tide is high, and the water is lapping at the edges of the Southbank, and I wonder if the current is strong enough to drag me under, and I can hear the sounds of skateboarders in the distance, and old couples are walking arm in arm, and young couples are walking arm in arm, and others are standing alone like me and staring into the water and thinking about things that they will always carry with them and never get away from because that is the human condition, and it is these memories that make us, and it is these images that make us, and I wouldn’t have it any other way, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Morgan Quaintance is a London-based artist and writer. His moving image work has been shown and exhibited widely at festivals and institutions including: MOMA, New York; McEvoy Foundation for the Arts, San Francisco; Konsthall C, Sweden; David Dale, Glasgow; European Media Art Festival, Germany; Alchemy Film and Arts Festival, Scotland; Images Festival, Toronto; International Film Festival Rotterdam; and Third Horizon Film Festival, Miami. He is the recipient of the 2021 Best Documentary Short Film Award at Tacoma Film Festival, USA; the Explora Award at Curtocircuito International Film Festival, Santiago de Compostela; UK Short Film Award at Open City Documentary Film Festival, London, the Jean Vigo Prize for Best Director at Punto de Vista, Spain, and the 2021 Best Experimental Film Award at Curtas Vila do Conde, Portugal, all for the film Surviving You, Always (2021); the 2020 New Vision Award at CPH:DOX, Denmark and the 2020 Best Experimental Film award at Curtas Vila Do Conde, Portugal, both for the film South (2020).