Sediment

Shoveling the earth is a symbolic and fundamental act. As opposites on a continuum, one can bury or unearth, forget or recover, obligate or excavate—all in tandem with life’s bittersweet cycle of growth and decay. The earth crust acts as the borderline between being and non-being for the living. Some time ago, a group of friends gathered at the gravesite in a fond farewell to our beloved compatriot. We took turns dumping a shovelful of dirt onto the casket and tossing personal objects into the deep hole to accompany our friend on her journey. We carry out these burial rituals in hopes of some closure and as I recall, our musings were really about ourselves. What the living desire is for the dead to stay buried and have an end to the narrative. But like the return of the repressed and the vampiric undead, themes and motifs resurface from the unconscious pool of history and memory and collectively it is what holds us all together.

Sometime in the early 1980s, I visited Ernest Dichter in Peekskill after reading the chapter on him in The Feminine Mystique and as it turned out, I worked for him for about a year. Active since the 1940’s, Dichter was a psychologist who developed the field of consumer motivation—that is, the technique of applying psychological principles to advertising to influence consumer choices. Forest Lawn hired Dichter in 1952 to do a study on the desires and fears of the living when faced with the dead. Dichter hid a microphone behind a coffin and recorded what mourners were saying when they came close and he determined that the living wanted to make sure the dead were comfortably still and would not rise, and relegate vampire lore to the confines of literature.

To bury the dead ‘6 feet under’ is a salve to the living and Dichter’s study led to an ad campaign for the comfortable, sleep inducing resting place that remains Forest Lawn. A mechanical waxworks at Madame Tussauds animates the dead. The striking automaton Sleeping Beauty is a dreamy figure, with a motor that makes her breast rise and fall subtly, as if she were alive and breathing. The soothing regularity of her breathing and the passivity of her pose—a classic woman to be gazed upon—but there are dangers in fetishizing this sleeper’s magnetic appeal.

K and I took a bus across Turkey in 1998 on our way to visit my Dad’s family in Syria. We made a stop at Çatalhöyük, an archeological site in the middle of nowhere and off the tourist map. I was excited to check out the bull head shrines and female deities that I had read about as I was always on the lookout for the elusive matriarchy. Having read Helen Diner’s Mothers and Amazons in my youth, it seemed likely that with enough digging the ancient matriarchy would eventually be found. But around the same age, I also read what was basically the counter argument in Engels’ Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State—a fairly grim assessment of women’s position in the patriarchy. The archeologist who ‘discovered’ Çatalhöyük decades earlier figured the society had a female centric or a female dominant social order because of the iconography he found. It sounded good to me even though I know the quest for a model past is doomed to disappoint. It is fraught with the violent history of conquest and colonialism but the material traces and inventions of lives once led offer an intricate puzzle for speculation.

Bent over the ground were a number of diggers toiling away the hot sun, silent and unfriendly, dusting short stacks of mud bricks and measuring small depressions in the earth. The question of the relationship between the bricks and historical truth was too big for that moment. And this was no place for the uninitiated—we were unable to make the landscape readable— or make the disparate images a system of ideas. We wandered around for a while, took some pictures and went on our way.

When I was a kid, my Dad was a traveling salesman in the carpet business. Euwer’s Truly was one of his regular stops. He specialized in what was, at the time, new—indoor/outdoor carpet and artificial grass. The end of my father’s life was a bit of a bungled affair, typical of my family. He had announced that he wanted to be cremated instead of being ripped off by the death merchants. But sometime in the early 1960’s my parents bought several plots in the cemetery and as a vet Dad had a free headstone. His kids wanted a public funeral so he was embalmed and on view for final farewells. Then his body was cremated and his ashes cast out in a small ceremony.

Today the cemetery plots remain empty even though we might have sold them— the funeral director explained to my sister and I that their location by the contemplation pond was the most sought after resting spot in the entire place. The magical journey of the dead as they abandon the flesh is poetically framed in the cataloging system of Aby Warburg’s great library. He worked for a lifetime to catalog human history and knowledge through an internal logic of how subject areas touch on and effect each other. The Afterlife section includes subcategories such as: 367 Hell, 370 Journey after Death, 375 Harrowing of Hell, 380 Judgement of the Dead, 385 Cult of the Dead and 390 Immortality. His subject areas track the customs of belief in the afterlife of the dead and also the afterlife of images that inspire and confirm those beliefs.

The emotional and intellectual power of classic, iconic imagery is reanimated and morphed through the ages. The toppled statue of a disgraced politician is preserved horizontally—he is laid to rest and contains, as an inverted and reformulated metaphor, the body of the dead christ.

My father’s ancestors converted to Christianity when the Crusaders cut through northern Syria on their way to Homs and on to Jerusalem. They built a massive castle complex, the Krak des Chevaliers in a strategic position overlooking the area. My father’s clan lived inside the confines of the Krak until the early 20th century when it was cleared out by the French. Many generations of my family settled in the nearby villages, and now most of the younger people have left because of the war and the ongoing misery. My cousin Samir grew up in the neighboring village of Habnemra and worked as a tour guide at the Krak until it became a conflict zone during the war, with rebel and government forces taking turns occupying the fortress or bombing it from above.

As my dad’s memory failed, he cycled through a shrinking set of stories and each time we heard one we tried our best to react enthusiastically. It seems that he and Perry Como, the famous crooner, were childhood buddies in the old neighborhood. Perry was from an Italian family of 13 kids and my dad a Syrian family of 9. When they were both around age 5, Perry was bitten by a dog and my dad watched from his kitchen window as the pet owner, an old Italian lady, rubbed a cutting of the fur of the dog into Perry’s wound as he howled in pain. “The hair of the dog that bit you” is an archaic expression—a cure for what ails you is a portion of that same thing—here acted out literally. In The Shining the bartender asked “What will you be drinking, Sir? Jack responds “Hair of the dog that bit me, Lloyd!” the Bartender confirms “Bourbon on the rocks.”

1 Maryanne’s Burial. Montrepose Cemetery, Kingston, NY

2 Kale from the Farmers Market. Kingston, NY

3 Sleeping Beauty. Madame Tussauds, London, England

4 Sleeping Gnomes. Catskill, NY

5 My Father. Sollon Funeral Home, Canonsburg, PA

6 Ernest Dichter’s Office. Peekskill, NY

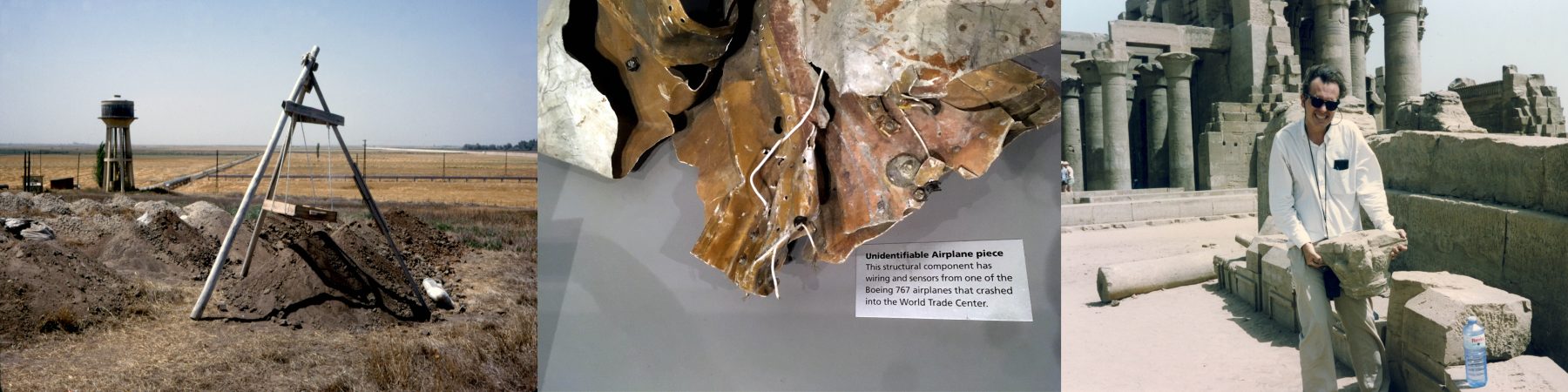

7 Archeological Dig. Çatalhöyük, Turkey

8 9/11 Plane Wreckage. The State Museum, Albany, NY

9 Stealing Ruins. Karnak, Egypt

10 Playground. Sabra & Shatila refugee camp, Lebanon

11 Trash. Brooklyn NY

12 Ethnographic Museum. Palmyra, Syria

13 Parking Lot. Zabriskie Point, Death Valley, CA

14 Krak des Chevaliers. Homs, Syria

15 Untitled (Ghardaïa) (2009) Kader Attia. Guggenheim Museum, NY

16 Girl Pointing. Garden of Eden, Lucas, KS

17 Edward Colston Statue on Display, M Shed, Bristol, England

18 Statue of Perry Como. Canonsburg, PA

19 Diorama of a Hungry Wolves. Zoology Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

20 Fortune Telling Cup. Museum of Witchcraft & Magic, Boscastle, England

21 Keith Standing In For Scale. Unité d’Habitation, Marseille, France

22 Soil from Five Boroughs. City Reliquary, Brooklyn, NY

23 Lion Foot of Carolee’s Table. Rosendale, NY

24 Sedlec Ossuary. Prague, Czech Republic

Peggy Ahwesh is a Brooklyn based media artist whose work has traversed a variety of technologies and styles in an inquiry into feminism, cultural identity and genre. She was featured in the Whitney Biennial (1991, 1995, 2002) and is represented by Microscope Gallery, New York. Vision Machines, a survey of media works, was presented at Spike Island (2021) and traveled to Kunsthall Stavanger (2022). Now Professor Emeritus, Ahwesh taught media production and history at Bard College, the Bard Prison Initiative and al-Quds Bard College, West Bank, Palestine.