Dry Ground Burning (Mato Seco em Chamas): A Conversation

Aily Nash: How did you come to collaborate with the actors in the film?

Joana Pimenta and Adirley Queirós: We searched for around six months to find Joana Darc, the actor who plays Chitara. We had constructed an archetypal character that we were departing from in our search: a woman in her mid thirties who would be the daughter of the single mothers who built Ceilândia, who worked at one of the gas stations in the city, and who smoked a lot. Because of the tension between the gasoline which adhered to her body after a day’s work at the gas station, and the lighter she kept using to light her cigarettes, she lived in the permanent tension that one day she would explode. We looked for Chitara in Ceilândia and in Sol Nascente for a long time, spending time in bars, in bakeries, in gas stations. It is obviously very difficult to convince someone to even talk to us about possibly making a film together in a place where there isn’t even a single movie theater, and there is no constructed imaginary of film production. When we encountered Chitara and finally managed to convince her to have a conversation with us, she said: “I know how to shoot a gun, I smoke a lot, and I’ve worked in a gas station, so let’s do it.” We knew we had found our protagonist.

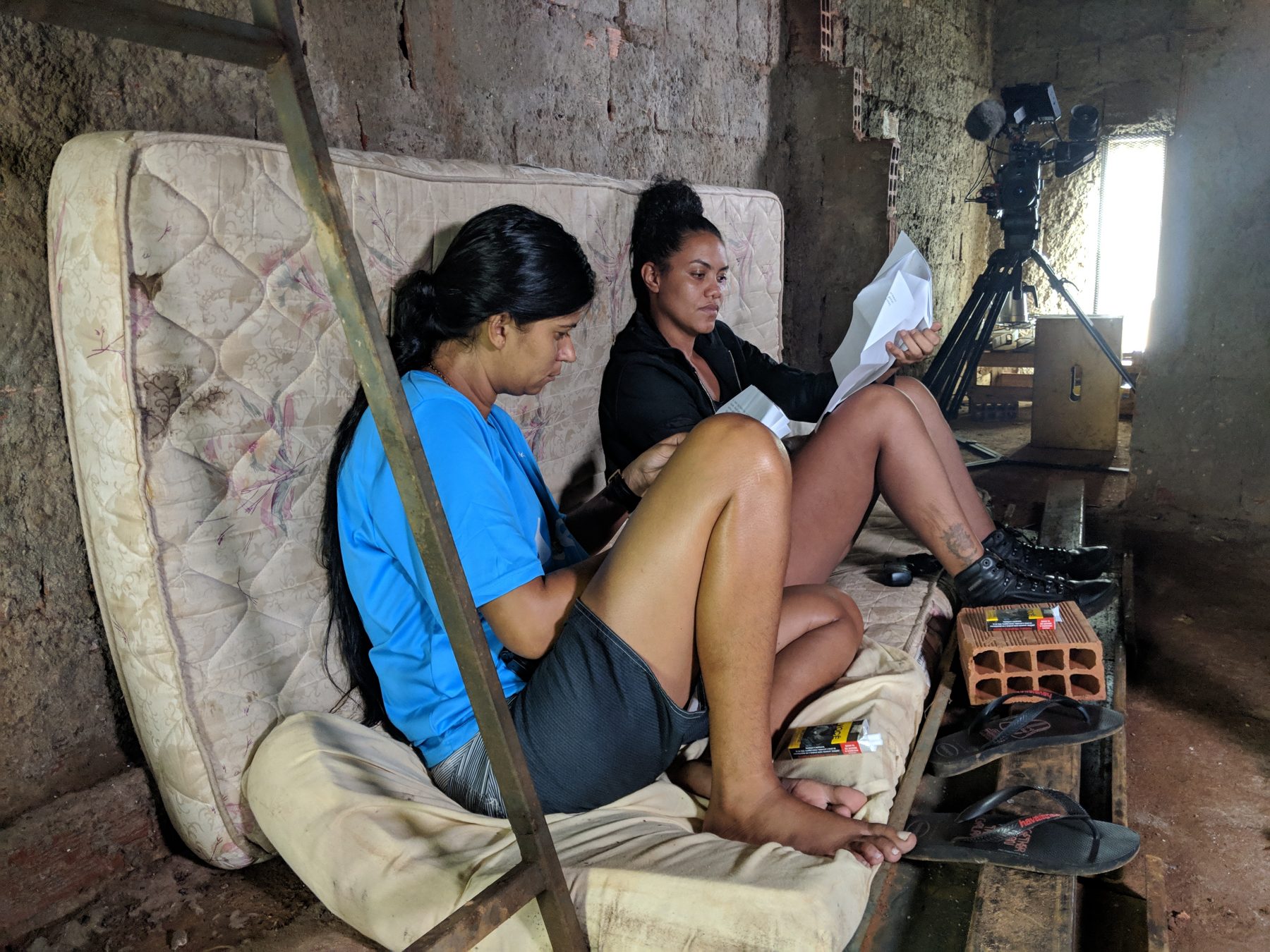

We initially had a twelve-month contract with her because the film is open-ended, we know the process is very long. We proposed locations, characters, and situations that we then experienced through shooting. We don’t write dialogue and we decide every night what we are going to film the following day. We don’t work with a closed script, but we propose situations that we often repeat. We work together almost every day, but often we don’t even film. We drink in the corner, we talk, we watch the afternoon go by, we drive around, we talk while walking through the city. We propose to the actors a narrative structure, a series of situations, an archetype for their characters, an imaginary. They reconfigure them by bringing their memory and their experience to the film. From those conversations emerge the situations we want to shoot. The film happens in the present, it reacts to the present, to what is happening to our lives, to the life of the city, to the politics of a country.

We filmed for around eight months with Chitara – and also Andreia, who comes from the previous film – before Léa appeared. Léa had been in prison for around seven years when we started shooting, and there was no indication she’d get out anytime soon. Her sentence had initially been for five years, but it was aggravated for behaviour (she was one of the commanding figures inside the prison). In the scenes we filmed, Andreia and Chitara often talked about Léa. Andreia knew Léa from prison, they had done time together, and she would bring the stories from the inside to her sister, to Chitara. She would say that Léa was a legend, that she was a leader to the other incarcerated people, that the police fired seven rubber bullets at her during a mutiny and she didn’t bend her knees, she carried on standing up, while the others were down after just one. She said they performed surgery on Léa in the prison cafeteria, in front of everyone, with no anesthesia because it was too late for that, to remove those seven rubber bullets because the guards didn’t want it to cause a problem for the prison if it became known they had fired so many at her. According to Andreia, Léa never lowered her head. One day, out of nowhere, when we had even begun to desperately look for a professional actor to play Léa because she was so omnipresent in the conversations we had recorded, Chitara sent us a message: Léa was back in the city! Less than two weeks later, she was already filming with us. And, of course, she was more than what we could have ever dreamed of.

At the beginning, Léa saw the film as a job. So much so that every time one of us would say, “Cut” she would disappear very quickly. We would find her when we were ready for the next shot standing on the roof, she had climbed the wall of the house! Or she’d be outside, looking at the street, smoking a cigarette. Of course, she is an amazing actor and she very quickly learned the codes of performing for cinema: in terms of holding her look, of the direction of the shot, of framing, of repetition, etc. She’d say, “it’s the same as when you’re in prison, you tell the same story a million times, you make the same gestures a million times, you have to make sure you capture the attention of the other inmates, even as you are repeating yourself, otherwise you lose your power to command.” From the moment Léa started working with us, the film changed radically, even if we had already filmed for eight months before she appeared. Léa imposed herself as one of the main characters, and it is through her that comes that very direct relation to the imaginary of the prison. As we shoot a film that is always open, always reacting, always leaving open the possibility of transforming itself based on what happens during the shoot, that change of direction is always possible. As long as there is money left for gas and food and to pay people, we carry on shooting. We film with a small crew, which fits in a car, so that we can film over an extended period of time and leave the film open to what happens in the life it takes. Léa came in to take the film out of a place and pushed it in a different direction, and because of the production model we established we could follow her. The film is always open to taking chances.

AN: You’ve spoken about your approach to making this film as an “ethnography of fiction”. Can you elaborate?

JP and AQ: It is important to see that the encounter between us both also brings into collision two ideas of ethnography, one being the ethnography of fiction that Adirley has worked with for a very long time, the other an appropriation of sensory ethnography that Joana brings from her ongoing work with the Sensory Ethnography Lab for more than a decade now. Ethnography of fiction is a process we propose with the aim of arriving at a political fable which re-signifies a collective memory. We interfere in the historical present to imagine a possible future. We propose to the protagonists fictional histories, and archetypes of bodies ready for a confrontation with the real, with the space constructed by contemporary political narratives. We work mostly with non-professional actors, people who do not follow the classical codes of representation in cinema. Together with them, we depart from what we propose and the memories and directions that they bring into play to construct a character for the film. In parallel, we build for these characters “sets” or locations where their actions will take place. Those sets can be built from scratch, or they can be appropriated from structures already existent in the city. When the actors believe in the character we construct together, and when they take ownership of the locations we constructed for them – in sum, when both an image and imaginary are built for us all – we then propose an ethnographic approach. At that moment we begin to film as a documentary. We believe that creating a space such as this builds a directed and shared focus between actors and crew, an attentive form of looking, and opens a necessary space for the improvising, for invention, and for accidents to take place. In general terms, we propose fictional characters which we film as a documentary. We hope that through this process the lines between both become blurred, and hopefully erased. Fiction is the process through which we can get to the real: not the burden of a faithfulness to a lived reality, but the playful space of a reality as we may imagine it together.

For example, when Chitara agreed to embark on the film with us, we went to look for the lot where she would build the oil platforms, and she would often come along with us. We’d drive around together for hours, talking about her character, looking at the city, thinking about where her character would move, work, live. We don’t close anything down or impose cinema onto the space of the street. Especially as we are beginning the film, a lot of time is spent negotiating the locations with the neighbours, at the site, telling and re-telling the story, narrating to everyone what this thing of cinema that we will be doing there over the next year is. Chitara was often part of that process even before we had found the lot. Once we found it she was part of building the imaginary of the oil platforms that we would build. The lot was covered in corn, and one of the first scenes we filmed together (that is now at the end of the film, almost as a memory) is when she drives her car over the corn and enters the lot for the first time as a character. From then on, the art direction team (Denise Vieira and Franklin Ferreira – Franklin is also an actor in the film, he’s the one who drives Brutus, the militia car) started building the platforms alongside our shooting. We filmed the entire process of Chitara building her lot, as if she was commanding the construction. The art direction would work during the day, appropriating and reconstructing existing machines we would find in junkyards and making them ready for oil extraction; and we would film with Chitara often at night, as if she were assembling the machines herself. In that sense, the construction of the sets and the work of directing the actors advance side by side. Everything is functional in the film, there are no elements of “decoration”, if you press a button something will happen, and the actors need to know how to use the sets as if it were their own homes. Likewise, we don’t use any cinema lights, all the lights are embedded in the locations (we add old street lamps to the outside, fluorescent lights to the inside, etc.), so the actors are also able to control the lights when they are performing. In that sense, when everything is finally built and we are ready to shoot, Chitara knows exactly where everything is and how everything works. That lot is hers as much as it belongs to the film. The fiction we proposed at the beginning thus becomes an everyday reality and then we can truly film as an ethnography, as a documentary of a fiction that is, at that point, everything but fictional for us. We have worked long enough to believe it has become a reality, at least our reality for a moment. At one point, even the neighbours thought we had found oil for real and that the film was just a decoy! It started going around that we were saying we were shooting a film so we wouldn’t get caught for illegal oil digging.

AN: In working with those depicted in the film, you enacted a form of role play in which they would play the role of actors, and you would play the role of filmmakers. Please say more about this.

JP and AQ: This has a strong connection with that idea of an ethnography of fiction we were just discussing. The protagonists are actors, provoked by a script, believing in the fable of the film, and receiving a monthly salary to work over an extended period of time. In that sense, what we propose to them is a mixture between labour and imagination, something that is not very common in their daily lives; an extraordinary situation. They play the role of actors, they bring memories of their past, they modify that past with the elements of the archetypes we proposed for each character. In that process we wanted to create a space where they didn’t feel like they needed to respond to an imposed or expected form of behaviour, where their strength could also come from expurgating a guilt imposed by society to the attitudes they had when they were younger. What was previously framed as shameful becomes an element of their strength in the film. Their lived experiences are reified not just as elements of an insurmountable condition of cyclical oppression and suffering, but as an important history of fighting. And that is very powerful because it moves to the centre, not only their present struggle, but also the possibility of future confrontations. As you say, we also perform the role of filmmakers in this context. In a sense, we all play this game of cinema. We make the film believing in the possibilities created by their performances, of the capacity those performances have of inscribing themselves in the imaginary of the people who inhabit the city, more than we believe in the mastery of a certain cinematographic technique. Cinema empowers us — us and them — with a living material that is the power of our collective imagination. In that sense, in terms of the effective performance of our bodies in the political territory that we film, more important than the edited film, is the memory which remains in the city of the performances that constructed it.

AN: The turmoil of the Brazilian political landscape is reflected in the primary narrative of the film – Lea and Chitara literally making the oil theirs — a contemporary Robin Hood narrative of redirecting the natural resources of the land to those who are disenfranchised by the state. How did this become the core of the film?

JP and AQ: Oil has always been part of the political imaginary of Brazil. In many moments of its history, it was mobilized as a narrative for the construction of an idea of nation. The nationalist idea of Brazilian oil was one of the elements in an ideological amalgam used to unite a complex and heterogeneous people. Recently, during the entire cycle of the PT government (the Workers’ Party stayed in government for a total of thirteen years, composed by two mandates of President Lula, summing up eight years, one complete mandate of President Dilma, and one interrupted) that narrative grew stronger and materialized into what became known as the pre-salt. The pre-salt is a vast oil reserve deep under the salt layer in the Brazilian sea, where it is estimated that 80 billion barrels can be found, which would put Brazil as the sixth biggest oil producer, just behind Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, and UAE. Effectively, it was from the pre-salt that the Brazilian oil emerged abundantly. “The oil is ours” had been a slogan since the implantation of the Republic. When the oil was finally ours, a promise could have been fulfilled. But the possibility of the oil being appropriated by the popular classes never materialized, and any real movement towards it was rapidly halted. Oil could exist as a source of national pride, but never as a possibility of income distribution, the means of class mobility, and thus the possibility of a fairer country. We were interested precisely in appropriating that imaginary, in changing the grammar of the official discourse, in tainting the institutional slogan. We departed from the standpoint that oil should be nationalized, and if peripheral people could effectively appropriate that oil, the entire economic structure of the country would have to change. The political nomenclature would have to be rewritten, and the slogan “the oil is ours” would have to encompass the people that never entirely fit into the borders it defined. To appropriate a resource whose only owner at the time was the state (supported by the power of making the laws and the possibility of using state violence against those who eventually insubordinate against those laws) is a task which requires violence, insurgency, and disrespect towards the law. The actors of the film have always lived in that reality. They had experiences which led them to imprisonment (although it is important to also note that imprisonment in Brazil is a political project used to contain a form of social revolt, a violent process of removal to promote social and population control). In that sense, the atmosphere for the film was set up. We brought together the potent imaginary the actors were bringing to the film, as part of their memory and their experience, with the possibility of a discourse against the state.

At the moment when the pre-salt was about to afford dividends to the popular classes, generating a possibility of social mobility to those classes, the Brazilian elite, armed by its judicial body, created what became known as Operation Car Wash. That operation accused Petrobrás, the Brazilian national oil company, of being the most corrupt company in Latin America. Not that corruption is not intrinsic to the Brazilian elites. But what was behind this operation was an unprecedented dismantling of a state policy whose principal focus was to benefit the masses, since a large percentage of the royalties from oil would have reverted to education, health, and infrastructure. In fact, soon after the coup that deposed President Dilma, first with the Temer government and then with Bolsonaro, the oil reserves of pre-salt were sold at the price of bananas to international multinational companies. In that sense, we started filming in a pre-salt Brazil and ended in an anti-pre-salt Brazil. After Bolsonaro came to power, what we had been proposing for the film in terms of the imaginary of oil we wanted to deal with had rapidly, and radically, transformed. We had started writing this film in a past reality where oil royalties were about to be directed to education and health; shortly thereafter, the new government had reverted that law, and it was putting in the international market as many oil reserves as it could get its hands on. In that sense, soon after we had begun shooting, the political oil landscape of Brazil, the premise from which we had departed, was already anachronic. That brought a form of melancholy to what we were doing. The film now began with an anachronism, and it had to respond to its new landscape. It could no longer be about extracting and appropriating oil – we now had to steal the oil if we ever wanted to make it ours. There is an underground oil pipe that brings the oil from the deep sea reserve in Paulínia, in São Paulo, to Brasília. That pipe runs right under Sol Nascente. Since the land in Sol Nascente was mostly illegally occupied by its inhabitants, and the city grew at the revelry of territorial planning, no one could have predicted that a city would be erected right above that underground oil tubing. If we wanted to steal the oil from the government, we just had to choose the right lot, and dig right under our feet.

AN: The urgency of this film feels tied to this specific moment during the Bolsonaro regime. Can you speak to how this moment necessitated the telling of these women’s experiences? Would you say that regardless of the political party in power, the community in Sol Nascente has historically been marginalized?

JP and AQ: The popular classes – in which we include not only the urban peripheries but also the indigenous communities, the migrants from the sertão, the quilombolas – have always been discriminated against and pragmatically incarcerated in Brazil. This project of incarceration is imbricated in the very idea of the construction of a Brazilian nation and it begins in the colonial process. What existed with the Bolsonaro regime was an exacerbation of this imaginary of what constitutes, and who qualifies, as a Brazilian citizen. Who is Brazilian? What is the social profile of a Brazilian? Bolsonaro is a populist, a fascist, and as such he needed to aggravate the territorial disputes. He used his discourse of imposing order to weaken the popular struggle against the owners of the power, the land, against the market, and all the implications it creates. So yes, the film proposes to create a confrontation with Bolsonaro’s aseptic discourse. Bolsonaro preaches order to reify class privileges, to exploit and ravage the Brazilian territory. Our film creates a sublayer of disorder to reestablish a struggle for more equal rights and the possibility to fight again for politics. If it is reified by an idea of “order”, politics remains unattainable. Disorder changes the game. Cinema can promote that imagetic disorder, that political dispute.

The film undoubtedly takes the side of the women we worked with, who were always discriminated against, despite the political party in power, progressive or conservative. The Bolsonaro government just intensified the discrimination against them. They are the anti-body to Bolsonarism, they are the body of disorder, the body ready to fight. The Bolsonaro government is patriarchal, it reestablishes the centrality of the powerful white man, where everything gravitates around the ethics and morals of the “good citizen” – a passive, pacific, and ordered man, who adheres to the commanding voice of the president. Everything in the bodies of Léa, Chitara, and Andreia is a threat to that order, a disrespect to that ethics and to those morals: the grammar of their language, the visuality of their clothing, their memories, and the inevitable disbelief in “order and progress” that the oppression they have experienced imposes. From all that comes a very powerful political force that they represent as the possibility of a future of a country.

Evidently the Bolsonaro government represents the highest degree of violence towards those bodies. So we can safely say that yes, that is our number one enemy. Nonetheless, as you suggest, it is important to reflect that what these protagonists represent, in terms of their radicality and their contradictions, also creates a discomfort for the progressive aisle in Brazilian politics since it can’t be contained by the progressive handbook. The progressive handbook defines a body who inhabits a geographical centre, someone who is intellectualized, an advocate of good taste, a believer in the separation between religion and power, and is inherently anti-violence. The periphery, by definition, is the opposite from that. Brazilian cinema has historically adhered to that progressive handbook and lost sight of the imagetic possibilities and the violence of the periphery as a political force. The representation of the periphery in cinema (and in politics) has always been dictated by a perspective belonging to the centre, appeasing the energy of the bodies, turning them into docile beings, conditioned just by their suffering.

AN: Will you speak about Sol Nascente, which has been described as the periphery of the periphery of the capital city Brasília. This is Adirley’s home and the setting of this film. What are the political implications of such a geography?

JP and AQ: When we started making this film, Sol Nascente was still a neighbourhood of the city of Ceilândia. When we finished, after the presidential election of 2018, Sol Nascente had become the largest “Administrative District” of the Federal District, the RA XXXIII, the most recent satellite-city of Brasília. Here in the Federal District, any periphery is named a “satellite” of Brasília. It’s a hallucination that always brings us back to the imaginary of science fiction. The city of Ceilândia was the first peripheral territory of the Federal District. Ceilândia was created in 1971 and it is known as RA IX. In the last 51 years, other 24 new satellite-cities have emerged, one on top of another, squeezing and turning the imaginary wings of Oscar Niemeyer’s airplane into vast peripheries (Brasília is a city that was designed and planned in the form of an airplane).

Ceilândia thus emerges eleven years after Brasília was constructed, determined by its own name: C-E-I is an abbreviation of Campaign for the Eradication of the Invaders. With the passing of time, everything that could be a stigma deriving from that name, which was meant to be shameful for the inhabitants of the city, becomes a shield for the people who live in Ceilândia. Generation after generation we have transformed that name in poetry, music, a football team, and a pride, a shield glazed by the memory and the feeling of fighting for everyone who was born here and everyone who lives here.

The process of construction of Ceilândia was dramatic. By 1971, Brasília was already completely built. The initial plan had given place to its modernist buildings and roads, a true postcard which was a source of pride for the state, the nation, and the academic and artistic elites of Brazil. But something stained that postcard: a large favela, home to around 100.000 people, which was placed right next to Brasilia’s international airport. People from all over the world who came to see, for the first time, the latest and greatest work of Brazilian modernism, the supposed example of the most equalitarian city, would have to face the favela first. This is a contradiction common in large urban centres in Latin America.

In 1971, Brazil was still governed by a military regime. Freedom of expression and free press were prohibited. That favela – which was multiple, which encompassed many situations and many worlds interacting in its space – was inhabited mostly by men and women who had come to work on the construction of Brasília. When the construction ended, the Brazilian state decided that those people were no longer useful, and they no longer had a right to be there. They had built the city, but obviously were no longer welcome in it. After all, Brasília was a city built for politicians, for public servants of the highest echelons, and for the Brazilian intellectuals. Those people who had built Brasília, and who lived in the favela near the airport, were under the cut line for those whose work made them qualified to live in the city. They were mostly migrants, people from the sertão in the interior of Brazil, a sort of lumpenproletariat. In March 1971, in a true war operation which took less than two weeks, the Brazilian army removed these people out of Brasília and threw them 40 kilometres into the cerrado, in an area that was an insalubrious desert, dry, where there was no water, no electricity, or any kind of infrastructure. It is estimated that 80.000 people were removed as part of that operation. It was the beginning of an apartheid. Big trucks were lined up in order to forcefully remove people and their belongings, including the wood which formed the walls of their shacks, so that they could use it to build new shacks in that new city far away. With this operation, Brasília affirms its aseptic policy and it constitutes its broken mirror, the dystopia to its utopia: Ceilândia. Those in power thought that the people who had been removed would not withstand the conditions of the desert they had been brought to. As such, they would voluntarily abandon their migratory condition and return to their places of origin. However, that idea of a place of origin was no longer a reality for them. That place had been frozen in a distant past, and a new Brazil had been presented to them and had taken its place. Those people did not give up, they did not abandon their land, and they built the largest territory of the Federal District, Ceilândia, which today is home to half a million people, with three generations of histories of fighting against the historical prejudice that was at the genesis of the formation of their territory.

The groups of people who came to Ceilândia in March 1971 were very heterogeneous. The neighbourhoods that had been removed had both informal workers and people employed in servicing Brasília: gardeners, guards, bakers, doormen, cleaners. There were also many people who came from nightly work at bars, restaurants, and clubs. A very curious fact, and also very violent, was that in the beginning of the construction of Brasília, the city was inhabited mostly by men who worked in the heavy realm of construction. At a certain moment, a tension had been established. These men had come to the city and had left their families in their places of origin. The government, trying to establish order in the workplace and assure the continuation of the construction that needed to be done, started bringing in women to work in the city at night, mostly in prostitution. One of these neighbourhoods, Morro do Urubú, was known as the home to a large number of brothels. The entirety of Morro do Urubú was also removed to Ceilândia, more specifically to Ceilândia Norte. Some of those women came pregnant, others carrying small children. Many of those children grew up without knowing who their father was. A big part of the first generation of young people in Ceilândia are thus the children of single mothers. This fact has also marked the second and third generations. In our film, we wanted to deal with that history and create a narrative that would be in dialogue with it, since despite it being very recent, it is also already forgotten. The protagonists in our film are part of a historical cycle of three generations of single mothers. The representations of this myth in the creation of Ceilândia, with its social and territorial characteristics, with its contradictions, interested us because it created an imaginary of fighting that we wanted to be very present in the film.

This city was under a continuous and intense form of oppression by the state, materialized by its police force. The CEI stereotype was easy material for criminal tabloids, and thus fueled a legitimization of police brutality and the aggressive actions they’d take against the people who live here. Here, the state has always acted in a pragmatic way, following a program of systematic incarceration. Myself, Adirley (as the question interpellates me directly), I have lived in this city since 1974. I was four years old when my parents, who were peasants by origin, arrived here. They arrived after being removed from the countryside, in a process that was very common at the beginning of landowner expansion, legitimized by the incipient idea of the landed property system which gave rise to the whole contemporary agribusiness policy in Brazil. I’ve lived in this city my whole life, I have met my friends here – many of them jailed or killed – and I have made all my films here (the three past features, and now this new film, co-directed with Joana Pimenta, who answers these questions with me.)

When urban planning arrives in Ceilândia, the centre expands, capitalizes, becomes inflated, and expels the poorest pioneers of the city. Sol Nascente first emerged as a neighbourhood of Ceilândia. It housed the poorest inhabitants of the city, who escaped the inflated cost of rent. So the expansion of the neighbourhood is initially made in its essence by people from Ceilândia who have lived the first removal from Brasília, and again live through a process of exodus to Sol Nascente. The removal process, a process of exclusion, is of a cyclical nature amongst the poorest and the peripheral, it always returns. This third generation of Ceilândia inhabitants, armed with their young children, many newborn, and with old parents and grandparents, repeat, almost as if in a reenactment, the expurgation done in 1971: they are thrown into a periphery of the periphery, and have to begin again the torment of building a new place to live. Rapidly, Sol Nascente grows to 200.000 inhabitants (besides the people who arrive from Ceilândia, many others come to the neighbourhood, impulsionated by the possibility of work that the imaginary of Brasília creates). With such a steep rise in population, politicians immediately become interested in turning the neighbourhood into a city. Many people, many votes. The political capital becomes open to those who campaign in that space. And that political capital is occupied mainly by groups connected to the evangelical church. That is determinant to understand what we may call “popular” in contemporary Brazil. We can no longer talk about public policy for the popular classes without taking into consideration the permanence of the evangelical church in the peripheries. The political left and the progressive groups, in my perspective, have taken a long time to understand that, if they have ever understood it at all. A large part of the people who live in Sol Nascente – which now with its official city status has been renamed RA XXXIII – have informal work (they are motorcycle delivery workers, street vendors, they work in market stalls, etc.), and many have been subjected to the carceral system, which takes a very quotidian presence in their lives.

The film, to a certain extent, tries to provoke a tension between what is idealized by the politics of these groups – them being either reactionary, conservative, or progressive – and the imaginary of peripheral people who have experienced very different trajectories. We are talking about a generation of people who were completely dispossessed and overlooked in terms of public policy by the state, who do not have an immediate connection with the identity groups and their often centre-based political slogans, who survive daily in a country polarized between the discourse of the right and that of the left, while both control the central narratives and forget the many nuances that fall in-between. We are talking about peripheral people who are not encompassed, and have never been, by the official discourse of what constitutes “Brazilianness.” In that sense, to make films in a place like this changes everything. It defies all expectations, it requires that the film changes constantly, that it is always open, many times fragile, but having the potential to be human and to be alive. To make films in a place like this doesn’t abide by the workbook of “correct cinema.” It is necessary to re-create a new model for production, and a new perspective towards technique and towards the idea of who qualifies as a professional in cinema. Joana and I have experienced and lived all these contradictions for more than three years, trying to understand what possible film could exist in this adventure we were living with Chitara, Léa, Andreia, China, Débora, Cocão, Franklin, and all the motoboys. We were all encompassed by this political and territorial trajectory of the imaginary of Brasília and Brazilianness. The corner is our agora. The corner is our ancestor.

AN: The carceral state and the relationship between life on the inside and the outside is palpable throughout the film. Can you speak about the ways in which their experiences on both sides shaped the film both narratively and how it was made? As Lea was in an out of prison during the film’s production.

JP and AQ: Sol Nascente is a territory where a large majority of the population has or had experiences with imprisonment. Either they are or were in prison, or they have a direct family member who is currently incarcerated. That led us to reflect what other imaginaries and narratives may be present in this place. To live with this carceral imaginary is a necessity, and to survive the material oppression that it brings, it is urgent to re-signify the intention of the reality that is imposed upon us. Cinema can do that. It can mobilize imagination and narratives which are often dismissed by the Brazilian progressive groups, who are only able to understand the political world through their intellectual and ethical filters which reflect an experience of living at the centre, in the urbanized centre, protected by the “state of well-being.” That state is completely absent in the peripheries.

To a certain extent, the prison is the most omnipresent public institution in this territory. The prison constructs the imaginary of the city, and reflects itself both in the larger narratives about the place and in the quotidian conversations. The stories begin on the street, continue being told in prison, and circle back onto the street. We wanted to reflect that temporal structure in the editing of the film. We wanted the film to have a circular structure, where past and present were confused, where a story that begins on the corner has its echo in the halls of Colmeia, Brasilia’s Women’s Prison, gets resignified, and comes back to the space of the street corner. That is why the film begins with Léa in the most recent present, after she is released from prison a second time and is under house arrest, narrating to us the legend of the gasolineiras. It was the idea of reimagining the history of her sister, the history of the stealing of oil, through Léa as a narrator, as someone who, in her own words, became a legend in Sol Nascente.

Léa heard about the film for the first time while she was still in prison. Another inmate with whom we were shooting for Andreia’s political campaign at the time (her name is Kárita and she was in the semi-open regime, and so she had the privilege to come home to Sol Nascente most weekends, but went back to sleep in prison during the weekdays) was the one who narrated to Léa the entire process of shooting. Two weeks after she was released, Léa was already filming with us. Léa was an apparition, a being from another planet, in more ways than one. Not only because she was immediately an amazing actor, with an unprecedented capacity for work and collaboration, but because she had been taken out of a very different world and just thrown back onto the world we live in. She didn’t know what a cell phone was, what social media was, and she would still, in those early days, out of instinct, lower her head and put her arms behind her back to walk down the street. She was as generous and giving as she was an imposing force on set. The first shot that we filmed with her (that is in the film!) is mostly out of focus because we as a crew, and Joana as the DP, were so intimidated by her larger-than-life nature as she walked into the frame.

When Léa finally got out, she brought with her the entire imaginary of the prison into the film. As we started shooting with her so soon after she was released, she still lived half on the inside, and she was eager to tell everyone in the film (Andreia, who had done time with her, and Chitara, who has never been arrested) about all the million adventures she had lived on the inside. As one of the leaders of many prisoner rebellions, Léa of course was very oppressed in prison, and was subject to a lot of brutal aggressions on the part of the carceral system. However, she resignified those stories for the other protagonists, she always told them as big adventures, proof not of the suffering they were subject to on the inside, but of the fact that they were winning. We as filmmakers never ask for “the truth,” the truth is for the police. We create fictional frames for them to tell us the stories they want to tell, the way they want to tell them. If they believe in the story they are telling, if it becomes true in cinema, it becomes an essential part of the reality of the film.

There is also the inverse path to that; Léa believes so much in the film that the story of the oil becomes a reality inside the prison. As she says in the letter she writes to her sister after she gets arrested a second time, it’s the story she tells the other inmates every night, after the lights go out, the story that echoes through the walls of Colmeia. We wanted Léa to become a legend both in prison and in Sol Nascente. One day we had the stupid idea that we needed to shoot her exiting the prison (we were worried we wouldn’t be able to make sense in editing of her “landing” in the film), so we took her back to the prison gate, on a Saturday morning, when all the inmates were being released. As soon as we realized the stupidity of what we were doing we wanted to cancel everything and go back home. We went to look for her to get her back into the car, but Léa was already hugging and chatting with all the other inmates whom she was so happy to see. They would ask her, “Léa, what the hell are you doing back here?”, and she would say, as Chitara recounts in the film, “I make cinema now, I’m an actor. We’re here shooting a film, we find oil in Sol Nascente, the oil belongs to my sister, but I help her.” That is the place between reality and imagination that we strive to construct altogether.

As it pertains to the prison, there is also, of course, the whole construction of the PPP, the Prison People Party. As the film was open-ended and reacts to the present we are living in, as soon as the 2018 political campaign began, we realized we needed to have a candidate, since there would be signs of political campaigns on the streets during the entirety of the shoot. As Lula was in prison at the time, we thought he could become our biggest electoral support on the inside. Andreia spent her life coming and going from prison, so we proposed to her to be the founder of a new party, the PPP, the Prison People Party. We enlisted Débora Glamourosa, a funk star in Sol Nascente, to work with Andreia on the jingle and on the communication aspect of the campaign. We rented a headquarters, worked with Andreia and Débora towards writing a campaign statement, and even collected the signatures to officially list it as a real campaign. Then we went out into the street. A lot of this material didn’t make it into the film, but we went door to door, we held rallies, we held meetings with the community. Our premise was the following: the preventive prisoners (people who are in jail awaiting trial but have not yet been convicted) have not lost their right to vote. There are around 16.000 of them in the Federal District. If we require the state to put a ballot box in every prison during the election period (which they never do, even though it’s in the law) and we get a large number of votes from the people on the inside, plus a couple from their families, that would be enough, in reality, to elect Andreia as a district deputy. We set out to campaign based on that premise. Once she was elected, she could enact real change in the district chambers. (Of course, the candidate who won the election was the police delegate, one of Bolsonaro’s men whose campaign we see a snippet of in the film.)

Then there is the more immediate, direct relation, with the carceral system. The process we see at the end of the film is Léa’s real process, even though the images look fabricated (it is hard to see what is going on in every picture, and we only see her face once). Some of the film’s viewers have told us in q&as they were certain it was fictional! When Léa was arrested the second time, during the shoot, she said she was an actor working with us, and we asked to go testify at her trial. While I (Joana) was in the waiting room, I struck up a conversation with the woman right next to me, who ended up being the policewoman who arrested Léa. I told her I was worried the trial was running late because I had come from the U.S., where I was working, to be a character witness, and I would have to miss more teaching if I had to stay for longer. She asked who I was here for, I said Léa’s name, and she said it couldn’t be, that she was sure I had the wrong person and had taken a trip for nothing! After much convincing of the judge that Léa could be an actor anywhere in the world (which we truly believe), we got their reluctant permission to move her to house arrest. She received three days out, 9am to 5pm, with her electronic bracelet activated, in order to finish the scenes we needed to finish the film. Since the film had gotten public funding, we could use the argument that the state would be working against itself if it didn’t allow us to finish the film. It is a small victory for her, for her amazing work as an actor, that recently, Léa has been invited to give a workshop on acting at the Colmeia prison, and a small victory for us that after Cinéma du Réel the film was invited to be distributed for a week in the internal open channel of three French prisons, streaming directly into the inmates’ cells at noon and at 9pm. We wonder if the people in charge of the prisons have seen the film, but that is a different story. There is something really beautiful in the fact that Léa’s legend can now enter the walls of an equally problematic carceral system, a world away from Sol Nascente.

The film sort of ends when Léa is arrested during the shoot, as it is very hard to come back from that violence into any kind of fiction. But we refused to let the film end with them losing, with the perpetual violence of the carceral system taking over. That’s why after her arrest, they all take over the vigilante’s truck and burn it. No one would know this besides a handful of people, but that truck that they burn is a Gurgel, a Brazilian-made car that is very hard to find, a symbol of nationalist pride. Any right-wing military man who sees that scene in the film is going to have a heart attack, for them it is a sacrilege that we would burn something so rare. We had so much fun tearing it apart, selling its pieces to chop shops, and burning the carcass. Léa emerges from that as a legend, to the sound of a rap song, DF Faroeste, that she used to listen to during the whole shoot and that we borrowed for the final scene of the film.

AN: There are playful flirtatious with genre throughout the film. At various moments, the film takes on the feeling of a western, a heist film, or an ethnographic documentary. It swiftly moves through the durational modes of each genre— the long takes of labour, extended domestic conversations, to wide shots of deep-rolling motorcycle crews, conflagration of vigilante vehicles etc. Can you speak to this?

JP and AQ: We tried to watch many films together, and we watched some of them with the actors. During that process, we searched for common references, films we could all share and make sense of in terms of what we were looking for in this film: the attempt to talk about a generation who lived on the corners, who experienced a Brazil which was very different from what it is today, a country very influenced by American films of the 1980s, 1990s, 2000s. Those are the only films that this generation watched. There were no theatres in the city and the films were seen on the public channel very late at night. They were bang bang (western films), futuristic science fictions, romantic comedies. Rarely would they screen a documentary, even one of the most classical television documentaries. It is funny to remember that when we approached the actors and said we wanted to make Mato Seco they would often ask, “but is it a documentary, or is it a film?”

Nonetheless, we are not exactly cinephiles, we didn’t really want to work with direct references, and perhaps we are actually both much more provoked and moved by literature when we are working on a film than by cinema. We wanted to try to take on genre, or different genres, in a meaningful way, not to approach them in some kind of pastiche or collage. So in our discussions it became important to really interrogate the form, aesthetics, and temporality, of all the different ideas we were bringing to the table. Above all, we were open to the way of shooting that each of the situations demanded. We filmed over a very extended period of time. That opened the film to the world, and to the many cinematographic genres that filming that world called for.

In terms of language, we knew we wanted a film that was spoken the same way we talk to each other on the street, that used a lot of slang, that believed in the poetics of the everyday use of a language that uses a number of invented words, or re-signifies entire expressions. The film in its original version is hard to understand even for native Brazilians, the protagonists talk very fast, and they speak the way they want to, there is a linguistic territory that is untranslatable outside of Sol Nascente. We like that form of owning the grammar and its possibility for miscomprehension. We would never subtitle the film, other than for a different language, and we always told the actors they should speak exactly as fast as they normally would, they shouldn’t make an effort to make themselves understandable for the camera, it’s the camera that needs to run after them and not the opposite. The structure of language appropriation was also important when we were thinking through the appropriation of different genres. The film starts as a western, we wanted to think about the possibilities and the limitations of the western within the context of Sol Nascente. The atmosphere of the city was already, of course, reminiscent of that genre, it begged for wide shots that showed the street corners, the houses, the dust, the sun hitting the walls, the relation between the bodies and space. The western became a reference also in terms of thinking through scale, as the film has mostly very wide shots and close ups, we rarely filmed medium shots. It also became a reference in regards to a way of editing within the shot. We would often compose the relation between the bodies and the site within the shot, paying particular attention to the way their bodies interacted with the space they were in. The wide shots allowed for that, as it allowed for the freedom for them to act and perform. But as the final rap song we use in the film goes (“DF Wild West scraping between gangs, and kids growing up in the middle of the Bang-Bang”), the western is also a very violent genre to be working with in terms of its history, and a very violent stereotype people already associate with Sol Nascente. So we wanted to break it apart, to open it up to contradiction, to turn it into a fictional-ethnographic-sci-fi-western that allowed us to work with different forms while also appropriating them, not adhering to one or the other, but rather work in a very free space between them.

In terms of observation, we had worked with sci-fi before, and that continues to be an important reference for us in order to play with an idea of ethnography. How can you even set a documentary in the future? Or in the case of Mato Seco, what kind of fidelity to observation exists in a film that keeps moving forward in a cyclical structure, where you are never sure what temporality you are living in, where past, present and future are thrown into collision? In the case of this film, the more observational work is often also the most fictional. For instance, in the scene you mention, Léa with her mother, that is her real mother and it’s the reenactment of a conversation they had had a couple of days before. But by that point we had been filming Léa in her house (she was under house arrest) for a month or more, so her mother was already very used to hearing about what could work for the film, she had seen it happen everyday for a long time: start with a premise, then repeat it, transform it, get somewhere else entirely, somewhere different even from what we had idealized… So while we derive forms and aesthetics from different genres, we are not at all intentional or purist in the way we do so, quite the contrary. Another example is Andreia and Chitara at work in the brick factory. Neither of them had ever worked there, but as soon as we knew where we wanted to film, they took it on as a job. They learned all the stages of the process, and so did we, and we worked alongside the other workers. However, it is also not just an ethnography of work, because obviously there is the influence that our presence in that space has, but there is also our way of filming the site as an ethnography of fiction, as something already between the real and the fictional. And that ethnography of fiction can morph into many genres. It is often the conditions of the filmed space, the negotiations we have to go through to film in a space, that define a path between the desire of the film and what reality offers it.

The genres are there if they serve our freedom to work playfully with reality, not if they are going to serve as another way to imprison people into an image. The film adapts to the present and to the sentiment of the protagonists. Naturally, during the process, they learned all the codes of cinema: the time to look, the silence, the language. Many times, they would see the images we were shooting while we were shooting or just after. They understood perfectly what we were after, what we were projecting as our desire for the film.

Joana Pimenta is a filmmaker from Portugal. Her short films The Figures Carved and An Aviation Field screened in Locarno, TIFF, NYFF, Rotterdam, Mar del Plata, among others, and received awards at Zinebi, Indielisboa, and Ann Arbor. She was also awarded the Best Cinematography Award at the 50th Festival of Brasília for Once it was Brasília. Her feature Dry Ground Burning, co-directed with Adirley Queirós, premiered at the 72nd Berlinale Forum and received the Grand Prix at Cinéma du Réel and the national and international competition awards at Indielisboa. Joana is a Lecturer in the department of Art, Film, and Visual Studies at Harvard University, Director of Graduate Studies for Critical Media Practice and Interim Director of the Film Study Center at Harvard. She is an affiliated member of the Sensory Ethnography Lab.

Adirley Queirós is a filmmaker from Ceilândia, a periphery of Brasília. After ten years as a professional soccer player, he started working in cinema and has since directed four features and a series of shorts. His previous film Once it was Brasilia (2017) premiered at the 70th Locarno Film Festival where it received the Special Mention Signs of Life. White Out Black In from 2014 was widely screened and won more than 20 awards in Brazil and abroad. His work has been shown at the Lincoln Center, Museum of the Moving image, the ICA London, Pacific Film Archive, and featured in publications such as Artforum, Cinemascope, and Cahiers du Cinéma. Adirley’s films have had theatrical releases in Brazil, the U.S., the UK, Argentina, and Portugal, among other countries, and are currently screening in the Criterion Collection channel. His latest feature, Dry Ground Burning, co-directed with Joana Pimenta, premiered at the 72nd Berlinale Forum in 2022 and received the Grand Prix at Cinéma du Réel and the national and international competition awards at Indiel