Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms: Restoring a Militant Cinema Network by Luna Hupperetz

Independent film producer, programmer and researcher Luna Hupperetz discusses restoring a militant cinema network with a focus on the film Women in Suriname (1978).

Women of Suriname screens at the Barbican on May 3rd as part of the Non-Aligned Film Archives screening series, curated by Annabelle Aventurin and Léa Morin in collaboration with Open City Documentary Festival.

This is a revised version of an article originally published in Non-Fiction Journal 02 in Autumn 2020.

“Cineclub in Amsterdam wanted to make a film about the way in which Surinamese women in their own country (and partly in the Netherlands) have to fight for their existence and that of their children. A praiseworthy effort, but the result was disappointing.” This review, written by a Dutch left-oriented liberal newspaper on September 23rd, 1978, discusses the film Women of Suriname (1978), a joint cinematic effort by two activist organisations: Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms and LOSON (‘The National Consultation of Surinamese Organisations in the Netherlands’) [1].[1] NRC Handelsblad, 23-09-1978. P 6.

The journalist critiqued the film for being overly political, as they wished for a film that “focused on the daily issues of the Surinamese Women.” Instead of living up to the ethnographic expectations of the Dutch viewers, Women of Suriname contains a bold voice-over that, in the style of militant cinema, directly addresses the viewer to reflect on how imperialism and Dutch colonialism impact the daily lives of the Surinamese people. Despite the fact that the film was widely screened throughout the Netherlands within the activist networks established by the Cineclub in the 1970s and 1980s, the film’s qualities were not recognized by film critics or media journalists. Now, more than forty years later, the film has been restored, digitized and screened in collaboration with those involved in the fight for an independent Suriname in the 1970s.

The history of the Cineclub

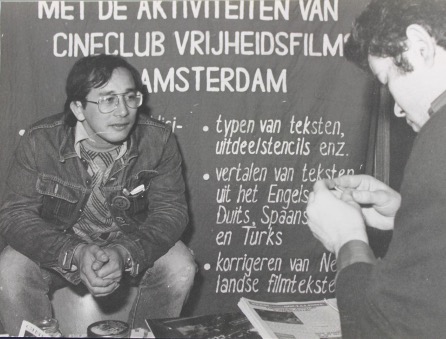

Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms was founded by filmmaker and political activist At van Praag (1940-1986), and ran from 1966 until 1986. The organisation was created as an activist film collective that could operate as a producer, distributor, and exhibitor of political and subversive film in the Netherlands. Cineclub’s screenings were initially an act of defiance against the dominant film circuit in the Netherlands, and against the power of national censors to withhold or withdraw films from circulation in the country’s cinemas of political film.[2][2] Subversive films did not reach the public theater due to either a lack of commercial interest by the NBB (Dutch Cinema Association), or due to political inappropriateness as decided by the CCFK … Continue reading Cineclub constructed a membership based ciné-club, which allowed them to show films in a semi-public screening format. Memberships could be purchased on the door, and the system served as an inventive way to bypass the censorship laws that were withholding or withdrawing political films from circulation in Dutch cinemas. Memberships were priced affordably, and the strategy proved successful.

In June 1968, the number of Cineclub memberships was estimated to be around 18,000.[3][3]”Cineclub Arnhem telt nu bijna 3000 leden, in het hele land tezamen tegen de 18.000.” Het Vrije Volk: democratisch-socialistisch dagblad. 18 June 1986. <“Advertentie”. … Continue reading In the beginning, Cineclub mainly programmed films in Amsterdam for politically engaged film audiences. After two years, due to an increasing interest from film clubs, cinephiles and activists situated in other Dutch cities, the “Cineclub Coordination Centre” (CCC) was established.[4][4] Molenaar 1968, pp. 150-151.The CCC wanted to improve the efficacy of what had become the three main activities of Cineclub: importing political films, and their translation, and national distribution. These efforts resulted in a collection of 135 film productions that included: material made by Latin American guerrilla movements in Cuba and Argentina; Western activist collectives such as ‘The Newsreel’ (USA) or ‘Cinegiornali liberi’ (Italy); the Black Panther Movement; communist propaganda from the People’s Army of Vietnam; as well as Cineclub’s own productions. Surveying the collection of both underground and classical third cinema films, shows that Cineclub played a vital role in the development of a Dutch non-commercial, activist film circuit, as they managed to sustain solidarity actions through the circulation of these films in the Netherlands.[5][5]https://search.iisg.amsterdam/Record/COLL00680#Ae49c501417 Nevertheless, the history of this collective and their collection has remained under-examined.

LOSON choir in the Moses and Aronchurch in Amsterdam

A militant cinema

The film Women of Suriname is the first film production by Cineclub that has been digitally restored. This film functions as a milestone in the collection, as it was their last production shot on 16mm and behelded a strong collaboration with the LOSON. LOSON was founded in 1973 by a group of Surinamese students in the Netherlands who supported the workers’ movement in Suriname and advocated for the social progress of Surinamese migrants in the Netherlands.

The film is known as the first film in Sranantongo, the English-based Creole language that serves as a lingua franca in Suriname (together with Dutch). For centuries Dutch colonial rule stigmatised this language as a low-prestige language. By reclaiming Sranantongo and centralising four Surinamese women from various ethnic backgrounds, Women of Suriname serves as an important example of anti-colonial film. The exhibition of this film in the Netherlands provided insights on the socio-economic and political situation in Suriname, countering a general ignorance towards the Dutch colonial history and providing more insights into the reasons behind the large numbers of Surinamese migration.

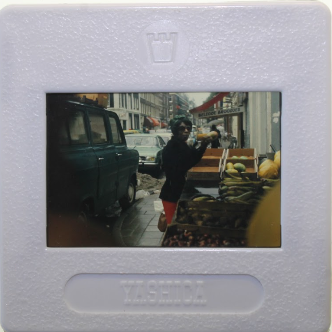

Apart from functioning as a pure indictment on Dutch colonial rule and imperialism, the film can retrospectively be understood as a monumental film that captures the spirit of leftist politics in Suriname. Shot in the lead up to Suriname’s independence from the Netherlands in 1975, it was released prior to the devastating military coup by former president Desi Bouterse in 1980. Since the declaration of independence, approximately 300.000 Surinamese—almost half of the Surinamese population—emigrated to the Netherlands, amongst which was Sonja Boekstaaf, whose experience is depicted in the film. Thus, in addition to documenting what the filmmakers called “The Unknown Suriname”, the film also sheds light on the hostile climate of racism in the Netherlands and the forms of resistance that were present through demonstrations and squatting.

Sonja Boekstaaf at the Albert Cuyp Market, Amsterdam

Film Act

As cineclub screenings would often be situated outside of the established cinemas, the diverging character of their cinematic practices in relation to the dominant theatrically centred film history, is exposed through their multiple positions as producer, distributor and exhibitor as well as through their understanding of film as a political tool. Cineclub’s involvement in political protests as documenters and programmers of the protests can be understood in the larger context of militant cinema, a global development defined by two cinematic movements from the 1960s: “Tercer Cine/Third Cinema”, in Argentina, and “Cinéma Militant”, in France. Militant cinema considered film as a tool for political intervention, with a new aesthetic form that was shaped by the available tools: lightweight film cameras and projectors, relatively cheap 16mm film gauge, and the emergence of sound-on-tape. Ideologically this new mode of filmmaking fulfilled a counter-informational role, raising themes such as serving the fight against social inequality, as seen in Misère au Borinage (Henri Storck and Joris Ivens, 1934) or Angela Davis: Portrait of a Revolutionary (Yolande DuLuart, 1972); neo-colonialism, as with La Hora de los Hornos (Grupo de Cine Liberación, 1968); environmental pollution, as in Lieber heute aktiv als morgen radioaktiv (Nina Gladitz, 1976); or capitalist exploitation of cities, like with Tolmers: Beginning or End (Philip Thompson, 1974), and natural resources, as in Dead Earth (Leonard M. Henny, 1970). In this regard Women of Suriname, which evolved out of a political solidarity between LOSON and Cineclub, fits into the characteristics of militant cinema.

Oema foe Sranan restored

In 2018 Floris Paalman, coordinator of the Preservation and Presentation of the Moving Image programme at the University of Amsterdam, initiated a collaboration with the International Institute of Social History to research the Cineclub film archive together with master students and curators of the Eye Filmmuseum. Upon discovering this film in the Cineclub collection, we looked—through both research and programming practices—to reconstruct the history of this film and its underlying contexts of the non-theatrical, non-commercial film circuit of the Netherlands from which it emerged.

During this research, we came into contact with former LOSON activists who worked on the production and distribution for Women of Suriname. When planning to screen Women of Suriname in 2020, we discovered that no high-resolution digital copy of this film existed, and that the most suitable print was degraded and discoloured.As such, we encountered various archival obstacles to our aim of presenting this film and its history to a wider audience. Some of these obstacles reveal how, in light of the Non-Aligned Film Archives proposition, a diverging practice such as militant cinema determines the future visibility of its efforts.

This first requires an explanation on the history of the Cineclub collection. In 1986, some of Cineclub production’s original negatives were found in a dump belonging to the now bankrupt Dutch Film Laboratory and stored at the International Institute of Social History. Years later, these found prints were merged with the previously mentioned distribution collection, unedited film tapes, photos, sound-tapes, and a paper archive of nearly 11 metres in length. Then, in 2003, this archive was acquired by one of the largest labour and social history archives in the world: the International Institute of Social History (IISH). In the Netherlands, the expertise and equipment necessary for the study of analogue film is now concentrated within just a few institutions such as the Eye Film Museum or the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision, where the IISH tends to transfer its 16 and 35mm stock due to a lack of in-house capability. As a result, even after its acquisition, the Cineclub film collection had remained unstudied for more than thirty years.

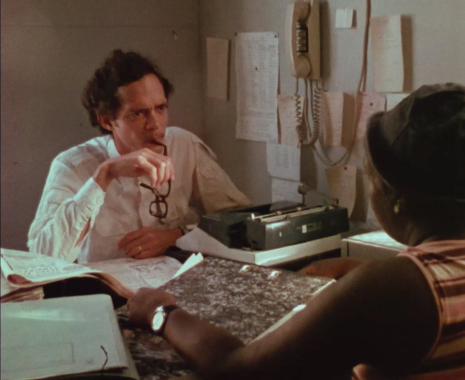

In order to tackle this accessibility issue, the University of Amsterdam, Eye Filmmuseum, and the IISH initiated the collaborative project of disclosing the Cineclub collection. In checking the physical state of the films, we looked not just for physical issues (such as mould, scratches, colour degradation, splices), but for material specificities that provide insights in the local appropriation practices of Cineclub (eg. inter-titles, Dutch translations in subtitles, or local action groups involved in the exhibiting of this film). For example, there was one distribution copy of the film Oema foe Sranan that had one specific scene cut out. Presumably this was a result of a screening hosted by feminist organisation that demanded to cut out a scene where a male government official misbehaved towards Miss Ferdinand. Such discoveries show how the films were constantly re-adapted for different screening contexts and based on audience response.

Still from Women of Suriname, Sylvie Fernand in conversation with a clerk from the custody board (performed by filmmaker Bram Behr).

Studying the accompanying paper archive also provided with insights on the production process of the film. Initially, Cineclub and LOSON had planned to produce a triptych of short films titled Unknown Surinam, comprising Oema foe Sranan, Mariënburg (about a sugar plantation), and Life under the smoke of Biliton (bauxite industry). These three films were intended to raise funds for a feature-length work entitled Djai Djai Sarnaam (meaning ‘long live Suriname’, as in the song featured throughout Oema foe Sranan) but their funding requests were denied and, deeming this to be an act of political censorship, they instead produced the mid-length film, Oema foe Sranan. Although the other two films were never made, audiovisual documents were recorded with workers from Mariënburg and Biliton between 1973 and 1976. In 2022, the first efforts were made to identify several 16mm materials related to the project but there remains numerous unseen film prints and audio tapes related to the Surinamese production in the Cineclub collection at the International Institute for Social History (IISH).

Eye curator Simona Monizza and ex-LOSON member Henk Lalji identifying rushes from the Women of Suriname production.

Archival strategy

The intention to reconnect with Cineclub’s practices through the programming of (what have over time become) archival films from its collection requires us not just the restoration of the film itself, but also a restitution of the network of actors that were involved in producing, distributing, and exhibiting these films across the 1970s and ‘80s. Organising a panel discussion with former LOSON members after the screening offers new insights into the cultural and historical value of this film that cannot be found in any archival documents. Vice versa, the presence of new audiences (often from younger generations) emphasized a new relevance for a film shot forty years ago. As the film has never before been screened in Suriname, the projectgroup Oema foe Sranan set up a collaboration with the National Archive of Suriname in order to realize sustainable storage and accessibility of the film in Suriname.

Conclusion

Presenting the film in context of the group’s historical activism, but also in light of the current preservation politics, this project brings together networks of activists and a new generation of cultural programmers, curators, archivists and other interested attendees. The historical militant network disrupts the institutional network, demanding the preservation and restoration of a cinematic monument that contributes to the shared history of Suriname and the Netherlands. In these times of digitalisation, curatorial programmes do not just reactivate the archive, but expand upon it, resurfacing and continuing the longstanding conversations surrounding a film’s preservation and contemporary value.