Armand Yervant Tufenkian on In the Manner of Smoke

By Claire Mullen & Stephen Kuster

In the Manner of Smoke (2025), Armand Yervant Tufenkain’s feature debut, takes its title from Leonardo da Vinci’s definition of sfumato, a technique used in Renaissance painting that softens transitions between colours and tones. As described by da Vinci in a note on painting from 1490–92, sfumato, whose rough translation from the Italian is ‘smoked off’, blurs the boundaries of figures by painting ‘without lines or borders, in the manner of smoke’. The resulting atmospheric quality casts a hazy veil, not only between the painting’s subject and background, but also between the viewer and the painting itself, most notably exemplified by the Mona Lisa. In In the Manner of Smoke, Tufenkian explores the possibilities of translating this technique to film, of realising a cinematic form of sfumato.

Shortly after winning the International Award at Cinéma du Réel, the film enjoyed two sold out screenings at Open City Documentary Festival, though the film’s relationship to documentary is murky. Like the medium-length Accession (2018), which Tufenkian co-directed with Tamer Hassan, In the Manner of Smoke’s subject matter drives its form. While Accession accumulates letters exchanged between heirloom seed savers with an almost archival logic, In the Manner of Smoke sketches fires, forests, and forms of practice in dispersing, diffusive drifts.

In first person, our narrator, voiced by Tufenkian, tells us how he became a lookout at Sequoia National Park in California. We accompany his apprenticeship – a solitary experience hinged on constant and close observation of the landscape. Alongside daily logs that report on the situation, growing paranoia and conversations with apparitions constitute the interior terrain of our narrator. Tufenkian only appears before the camera in a series of photographs taken in the semi-fictionalised downtown of Fresno, his body always blurred and out of focus. Throughout the film, a forest fire approaches – at first distant, then imminent. As it nears the lookout station in the evacuated area, our narrator sits watch alone, descending into what might be described as madness.

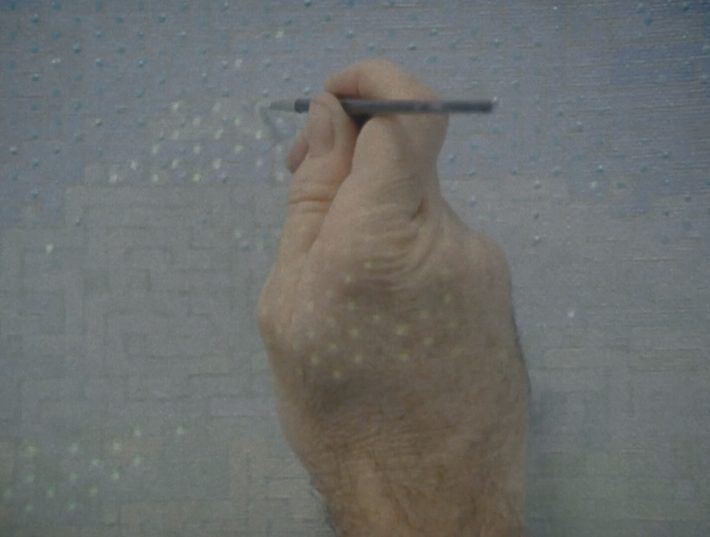

Tufenkian’s film approaches an observational mode of documentary with a particular interest in the process and duration of labour. A continuous, circular pan introduces us to the structure of the lookout. Its fenestrated walls oversee the landscape below, and its interior is populated by an electric stove, a twin bed, and an abundance of Smokey Bear paraphernalia. At the desk sits Mich Michigian, a veteran lookout. Throughout the film, Michigian performs the daily tasks required to keep watch over the fire-prone landscape. Instruments measure weather conditions, which get recorded in weather reports; radios transmit communications across the region. Meanwhile, Dan Hays, a London painter, is filmed producing a series of paintings from watchtower photographs of the Rough Fire that blazed through 151,623 acres of the National Park in 2015. We follow Hays’s artistic process from beginning to end, from the digital programs that help prepare the paintings’ pixel-based compositions, to the act of painting itself.

Shot in close-up, Hays’s working hands make us aware of the materiality of the image. The burning landscapes take form through the repetition of basic units, whether blocks, dots, or more labyrinthine shapes. Filming Hays and his paintings from various distances, Tufenkian shows both how these shapes come together to make an image and how these images become atomised upon closer inspection. As the camera nears the surface of these paintings, smoke escapes the confines of these units, their bounds and borders. Smoke remains intractable. The same holds true for the heterogenous images of smoke throughout the film, both digital and analogue. Whether pixel or grain, smoke always evades capture.

Despite their best efforts, the fire crew will not be able to contain the fire. It will blaze past the fire line that is meant to halt its movements and encroach upon the lookout. Drifting off to sleep with an image of his foretold death, our narrator does not speak of fear. Instead, he finds comfort in surrender. While this proposition feels at odds with an inherent fear of fire, and the loss of life and homes, the film’s speculative surrender suggests a different way of being in the world. It marks a departure from a colonial mode of mastery and a movement towards how we might live in places where fire has been part of the land’s rhythms long before the sprawl of suburbs and the arrival of settlers. That one might begin from a place of understanding rather than fear. Maybe such a being would not be human after all.

Claire Mullen: How and where did this project begin?

Armand Yervant Tufenkian: One of the threads began the last summer of filming for Accession. Tamer and I were in northern Idaho, and it was the first time I saw a forest fire with my own eyes. There’s a shot of that fire in Accession. There was this otherworldly presence that I had never experienced before, and it stuck with me.

That summer, I moved to Southern California and, along the way, I encountered multiple forest fires. I moved there to go to CalArts, and the second week of classes were cancelled because there was a fire in Laguna Canyon. Forest fires became a part of my everyday lived experience.

Many years before that, I was doing a writing workshop at Naropa University. In a workshop with Fred Moten, I was complaining to him about my dissertation project, which was on the poetics of community in cinema. He pointed me to this poem by Robert Duncan called ‘The Fire’. In that poem, Duncan references sfumato as a poetic device that both describes what’s happening in the poem and points to the poem’s content.

That idea of sfumato really struck me, because it dovetailed with this idea of the ‘ecotone’ that I’d been thinking about for a long time. In ecology, an ecotone is where two biological communities meet and overlap and, typically, it’s in the ecotone that you have the highest species diversity as well. So I was thinking: what would a poetics of smoke be in a film, and how would I go about achieving it, with the subject being forest fires?

Later, I was doing research to find information about practices around smoke communication in the Americas. I found some things here and there, but it isn’t really material that you encounter in archives. What I did find was this map of mounds that was developed by the Iroquois Nation and allied tribes. They were able to do long-distance communication with smoke. It was this system that made me realise that I would have to elevate myself physically in space in order to achieve the perspective I wanted for the film. That’s when the lookout idea presented itself to me, and I just got lucky. I had come to all this around February or March, and I reached out to the Buck Rock Foundation in the Northern Sequoia Forest. They happened to have an opening, so I started working and training that summer.

Stephen Kuster: I’m interested in how ‘The Fire’ provided an initial scaffolding for the film. Duncan’s writing moves through various elements, including word matrices, detailed descriptions of Renaissance paintings, and long block quotes. Notably, there is an extended ekphrasis of Piero di Cosimo’s painting ‘A Forest Fire,’ which we see in detail at the end of the film. In his description of Cosimo’s work, Duncan outlines sfumato as ‘a softening of outline’, a fusing of colour, and a ‘glow’ at the ‘old borders’. What did that evoke for you?

AYT: I think for me it was that Duncan doesn’t just state that there was a relation, but rather [through using sfumato as if it were a poetic device] shows us how it is related. Sfumato struck me as a way to think through what the poem is doing in the first place, which is taking all these heterogeneous forms of writing and piecing them together. That’s what I love about this poem. The poem tells us how it’s working very early on in the piece. Each part iterates a different form of writing, and the beginning and the ending of the poem have these word matrices. The word matrix was a guide throughout the making of the film, as this polyvalent montage approach best describes what happens intuitively in the editing process, when we have all these different valences that can connect with one another.

SK: You’ve already mentioned montage as a means of bringing together elements in the film that might otherwise be discrete. How else did you think about creating relationality through cinematic form? How did smoke help you conceptualise that?

AYT: I tried to create a cinematic form that resembled smoke in the way that it rises and disperses, as in the opening scene of the film. Smoke has this amazing relational capacity because it can disperse, it can blur, it can obfuscate, it can point. With sfumato, the idea is: what is the relationship between two things, between figure and ground? In the kind of films that I’m trying to make, I’m interested in what happens when we no longer look at the figure and instead look at what’s happening in the literal background. In Accession, it’s about saving seeds, right? Here, it’s about forest fires. Maybe that’s one iteration of the figure.

Then, how do you move and blur that relationship in this way? How do you create this figure-ground obfuscation, where it’s moving back and forth? How can you create a cinematic form that is moving along these different planes? And what happens? Is that a film? It is, I think.

In the Manner of Smoke (Armand Yervant Tufenkian, 2025)

SK: What struck us both was how you figure yourself into the film. This is the first time you’ve used first-person narration and it seems to be a blurring of the self. It’s not exactly autobiographical but you’re playing with that.

AYT: I was influenced by Fernando Pessoa’s writing, specifically The Book of Disquiet, which I read multiple times during the pandemic.

CM: Isn’t that in the film?

AYT: Yeah, nice catch. There’s a quote in The Book of Disquiet that ‘dreamed landscapes are merely the smoke from known landscapes’. Pessoa is all about heteronym and parafiction. Cinema has the privilege of being a visual medium, and I was so hesitant to include a voiceover in this film. That came towards the end of the process. I am aware of how words can steer the viewer, and I had to figure out how to write a text that wouldn’t do that, or that satisfied my interest in multiple valences and connection points. It was a big jump to include myself in any way, and I had to really challenge myself. That’s how I want to make work. I want to force myself to grow with each project.

There are also more practical matters when thinking about ‘big’ cinema and how fiction in cinema works. You need a script, you need actors, you need a crew. How could I work by myself to make a fiction film and not have to pay a lot of money? How does one go about doing that? It was a very practical decision: I had to include myself because I couldn’t afford to hire an actor.

CM: Would you call the film autobiographical?

AYT: No, because a lot of it didn’t actually happen. But it comes out of my experience. I don’t know what I would call it. Parafictional? I’m comfortable with that.

SK: Given its run at non-fiction festivals, what would you say about its relationship to documentary?

AYT: It’s interested in the real, the experience of living in the world and the actual experience of forest fires, or the actuality and presence of them. But I’m also interested in what the smoke of the real is. All these other quasi narratives, these potential digressions, these gestures to different directions that the narrative might take… I’ve been trying to call it a drama just to kind of see how people react to that… [Laughs] It is dramatic: there’s a fire approaching and I don’t know what to do.

CM: What have the reactions been?

AYT: So far people don’t really know what I’m talking about.

SK: I’m interested in what other work—whether that be the work of artists or thinkers or other filmmakers—you think of the film being in conversation with.

AYT: I had a great time delving into this filmic subgenre of ‘artists working’: from the Maysles brothers’ documentaries on the Christo and Jeanne-Claude projects, to Jem Cohen’s film about a sculptor, Anne Truitt Working. I was very drawn to the way that Ben Rivers shows Rose Wylie working in What Means Something.

I was trying to get at the question of how these films are made. Films about artists tend to feel promotional. You watch an artist at work, then you see the end product: a process-to-product relationship. It got me thinking about how artists are represented and about Salomé Skvirsky’s book The Process Genre.

For a long time, I was trying to make one part of the film be ‘How to Be a Lookout.’ I hoped that, through watching the film, you might learn a little bit about what it’s like to be a lookout. They showed us a lot of short instructional videos at the training, so I became interested in this how-to mode. What could cinema do as a pedagogical mode? Can you learn how to be a lookout through cinema? Maybe that’s the kind of film the people at the foundation thought I was making at first…

I also had this initial idea where the fictional aspect was going to include a network of guerilla fire lookouts all over California, potentially initiating a culture in which all of us would become lookouts.

CM: You’ve said the film took seven years to complete. It sounds like there were a number of iterations and changes.

AYT: Yes, a lot of shape-shifting. Partially it took so long because I wanted to spend a lot of time working as a lookout before I tried to represent it, so I worked for four fire seasons.

CM: In the film I think it was implied that you had worked there for two seasons?

AYT: Yeah, so that’s…

SK: Parafiction?

AYT: Yes. [Laughs] I didn’t start filming my own experience of being a lookout until the second or third year. In that sense, there’s an auto-ethnographic, or quasi-ethnographic element to it as well. I stepped into the world of these lookouts—many are retirees that live in the area—just being around them and learning about the culture of being a fire lookout. I was also spending time with Mich, becoming friends with her, and learning about how she got into it.

SK: What I really love about your film is that nothing is ever really pinned down. Elements arise but then dissipate. One strand that the film picks up is indigeneity. The Sequoia, for example, are described as the ‘Ancient Ones’, the ‘Wawona.’ How do you see the film engaging with indigeneity and colonialism?

AYT: There’s something about names that I’m working through in the film, the way that names have this indexical function of pointing. When we’re looking at the photos [from the aftermath of the Rough Fire] and Mich is listing the names of the areas—well, if you were to take it a step further in researching the names of those locations, it would point to colonial history in pretty much every case. Even if you spend a long time looking out at the landscape, there’s no way to know that history. You get to it through language and knowledge production, through texts.

In the case of the Wawona tree, it’s interesting to research where the name ‘sequoia’ comes from. There are two alternate explanations: one is that it references an indigenous person from the Eastern Americas, named Sequoia, then there’s another line of thought that they just made up the name at the moment.

In any case, I think using the name Wawona—which is what the Yokuts and the Mona, the people from that specific area where I was at in the National Park, now called Delilah, would call it—is part of the larger project of recognising Indigenous history. [Using the word Wawona] already does a lot of work in pointing to the fact that this is a native tree that thrived in this area, much more so than today. In the Northern Sequoia Forest there are still groves, but there are not many of them. Before, the whole forest was made up of these massive groves, cathedrals of sequoia trees. So even just introducing that name, for me, is trying to point to this pre-modern existence and to the epistemological frameworks that modernity imposes on us.

SK: As the film nears its end, the concept of surrender emerges. What might it mean to surrender to smoke or to fire?

AYT: There’s something about how the modern human has been trained to be afraid of fire, and to come up with ways to control it. As a result, this has exacerbated the ways we receive images of forest fires via various media, which show it to be purely destructive. It’s terrible. I’ve found there is space in renegotiating the way we relate to fires, to break away from these modern modes of being. Perhaps in surrendering ourselves to the power of fire, there is a certain kind of humility. An environmental humility and a humility as a person in the world. We might be able to live in a more balanced relationship with natural forces or things that we can’t or don’t know how to control.

We also hear about surrender in Buddhist studies, and there’s a way that relinquishing control is political. Becoming comfortable with relinquishing control is definitely not policy, but it’s deeply critical of the systems that are in place and the way that we are expected to work within them. This also relates to a subtext in the film. I’m okay with dying at the lookout, or my character is okay with dying and the lookout burning down. There’s something about trying to engage with ideas of impermanence. The Sequoia trees can’t control how long they live and how they live. They’re witnesses to what is happening around them, and the film is trying to connect that idea to how we live in the world.

CM: Speaking to this idea of surrender—as someone who grew up in California and has had to evacuate from fires—I was wondering how you think the film deals with fear and the very material reality of loss from fires?

AYT: In my research, I found the collection of emergency calls that were made during the Paradise fire, and you can hear people in burning houses, calling for help. It’s just about the realest you could get. So, in no way am I trying to aestheticise or diminish that experience, because it’s obviously very real.

I feel like there’s something about the way that California—or wherever humans have integrated themselves, or attempted to integrate themselves, into fire ecology landscapes—has not accounted for the reality of fire. It points to a larger cultural misunderstanding of what it means to live in a place where fire is endemic. Humans have chosen to integrate themselves on a massive scale without coming to terms with the reality of what fire is doing, and we’re seeing the results of that. I hope that the discourse on forest fires in California will progress to a point where we don’t have to resort to building houses in a certain way that is fireproof, but also where we understand that these are areas that we might not be able to inhabit. Or maybe we shouldn’t be inhabiting these areas unless we’re ready for the chance of fire.

So many people I know just lost their homes in Los Angeles, and I think about them watching this film. What will they feel about it? I don’t think the film necessarily has anything to say about the LA fires directly. I think the film is more about forest fires and less about these cataclysmic events in cities. It’s more me trying to process my own experience of living in California and being around fire prevention people.

That came up in the Q&A today. Someone was like ‘Your film is described as being about forest fires.’ I think that’s a larger conversation about how we describe films, what they’re doing and what they’re about. Sure, the film’s about forest fires, but it’s also not about forest fires. In a sense, it’s about what happens when you spend a long period of time by yourself.

This interview was conducted during Open City Documentary Festival 2025 in the framework of the Critics Workshop with Another Gaze.