The Elephant in the Karaoke Room

My father and I are well acquainted with the elephant from that phrase: the one that goes unacknowledged in a room, despite everyone being acutely aware of its presence. It sat in the backseat of the car on quiet drives to school. It jogged alongside us on frosty Sunday mornings through the Adelaide Hills. It joined us every Friday when we dined at our favourite restaurant.

象 [Zou]: Do you sometimes wish I spoke your language? Would we understand each other better if I did?

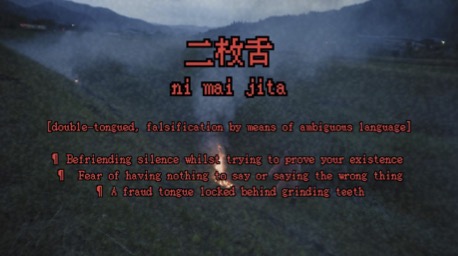

Last year I embarked on a film project titled Glossary of an Empty Orchestra (鏡花水月), filmed in and around my father’s hometown in Sōma, Fukushima and a karaoke room in Adelaide, Australia. In the film, the boundaries between reality, memories and dreams are temporarily dissolved in order to parallel my internal sense of liminality as a ‘hāfu’ (half-Japanese, half-Australian). My inability to speak Japanese is perhaps a symptom of growing up in Adelaide, where I was desperate to belong to my immediate surroundings. Ironically it is another quest for belonging that now has me learning Japanese as an adult. That is to say, I find myself at the age of 26 with the tongue of a Japanese toddler, taking awkward and ungainly steps into a language most expect me to already know. But like a toddler testing the boundaries of their new faculties, I play with these new words and sounds, putting them in my mouth, spitting them out, observing them again, all chewed up. I feel them grow inside me.

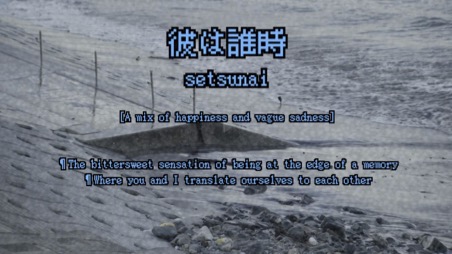

There is a Japanese phrase: 鏡花水月 (Kyouka Suigetsu), which translates to mirror flower, liquid moon. This yojijukugo (lexeme or idiom constructed from four Kanji characters) refers to seeing a flower in a mirror and the reflection of the moon on the water’s surface. These are entities that can be seen, but not touched. You can glean the beauty of the flower, you can admire the glistening of the moon on the water. However, the moment you reach out to grasp the thing, it’s gone. The flower is just cool glass on your fingers, the moon diffuses into the ripples of the water. Such moments, intangible and fleeting, can carry meaning from one thing to another. In other words, they translate. While 鏡花水月 became the Japanese title of my film, the English title became ‘Glossary of an Empty Orchestra’, which references the English translation of karaoke. In Japanese, kara means ‘empty’, while oke is a shortened version of the Japanese word okusutera, borrowed from the English word orchestra. In this way, the entangled etymology of the word karaoke helps disrupt any idea of fixed belonging and direct translation in language. This disruption is expanded on the screen- where I try to seek a sense of belonging amongst a fragmented sea of precarity. The vessel to communicate this uncertainty: narration spoken in my broken Japanese.

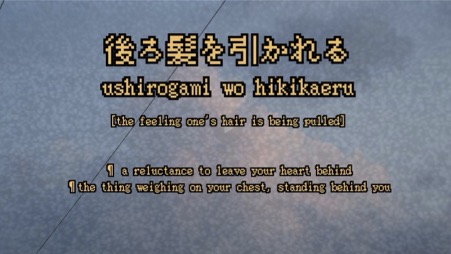

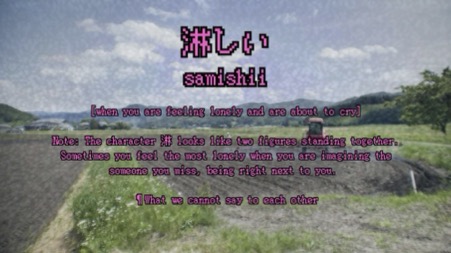

It is no coincidence that my film is filled with the same silence my father and I shared growing up. In many ways this silence becomes the sound of deep yearning, longing, what Polly Barton might name eros. In her novel Fifty Sounds (2021), Barton describes the distance between ourselves and the object of our desire as one of the defining features of eros. Distance becomes a necessary barrier, which gives form and direction to our desire. In my case and I suspect many others, “distance takes the stage dressed as language” (Barton, p.110). The Japanese language missing in me ensures I will return again and again to that space of distance: a hole. With me in the hole are the tools to build a ladder, symbols and sounds unfamiliar to my hands. If I learn to shape them into rungs and so build the ladder, the hole may disappear and potentially too, the eros.

The location of Sōma brings with it a particularly strong presence of yearn-filled silence where ghosts linger in spaces of inexorable feeling. It is located between two nightmares; the 2011 Tōhoku Tsunami and the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster. The film borders these events where ‘words don’t reach’. They meet in a gray zone defined by an absence that feels too large to name. Some may call it shock, stoicism, disbelief, pain, longing. They come to equal the same thing: a loss of words.

I recall a particularly silent car trip with my father from my childhood. He picked me up from my ballet lesson and we drove home. We are comfortable in silence, but on this day, the absence of words felt distinct, near tangible. When I got home I got a call from my mother telling me my Ojiichan (grandpa) had passed away. We were flying to Japan the next day for the funeral. I think about the silence in the car, and why my father could not find the words to tell me this news. Maybe he did have the words but they were too painful to say.

象 [Zou]: If only I could speak his language, would he have spoken to me in the tongue he shares with his father? Would it have eased some of the pain? Could I temporarily come out of the hole, to hold his hand?

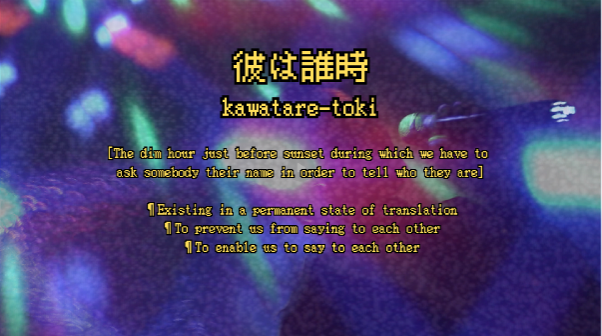

There are things that the Elephant grants us to say, precisely because it accompanies us. In the liminal waters of translation meaning can be drawn from infinite layers and creative frequencies can cross borders fluidly. To speak in my mother tongue can sometimes feel like a needle popping a balloon. In the abundant vocabulary that conjures itself in a second, thoughts and feelings express themselves too directly, too harshly with too much specificity. The mothertongue goes straight for the thing at the centre, when the thing itself lurks on the outskirts: soft, fragile, and frayed at the edges. Such feelings lend themselves well to the act of translation. Somewhere in between my slick mothertongue and my clumsy fathertongue there is an opportunity to capture the elusive cloud of existence, and experience. Perhaps this is because meaning opens up on the table, exposing itself as it undergoes translation. During the making of this film my father and I spent days translating the narration. ‘What does it mean though, to you?’ was the most common question. In order for my father and I to translate the script, I had to unpack the meaning I had tucked shyly away into the English subtitles. In this way, the act of translating forced me out of my hiding place. For every five minutes we spoke we grew one word, until we had a garden.

Because of this process the Japanese narration rarely translates the English subtitles. Instead we found new words and constructed parallel stories in order to approach the meaning from two directions. For example, in one scene we see the moving image of waves lapping up against a seawall. The subtitles read: “the waves trying to cling to the shore are my fingers gleaning for words”. Meanwhile, the Japanese narration says something like, “the sea salt lands on my tongue, eroding it.” The English subtitles embody the waves while the Japanese narration becomes the seawall. As we watch the waves slide over the seawall they meet for a brief moment, before separating again.

Words become absurd when you sit with them for too long. They lose meaning, become abstract, and separate themselves from the thing we are trying to name. In this way, words can erode memory in the same way time does. Perhaps then, we keep a memory alive by transforming and re-shaping it: by finding new words, new ways of communicating, new ways of encountering. Put another way, by engaging in the act of translation we are saying: I want to remember.

象 [Zou]: Here in the karaoke room there’s no silence, only singing. There are two microphones on the table, a jug of beer, a sad bowl of peanuts. There’s a phone on the wall should you wish to order more drinks- or peanuts for that matter. Above you is a swirling projector that shoots distorted colours around the room. There’s a TV on the wall where I’ve queued up your favourite songs. The space is rather small, so I’ll wait patiently at the door while you express yourselves through this act I cannot translate. When your voices grow tired I’ll escort you back out into the world. I’ll voice all your silences, and remember everything.

Mika Ogai is a Japanese-Australian filmmaker and writer currently residing in London. Graduating the University of Melbourne with a Bachelor of Arts in Screen Studies and Geography, Mika has always been drawn to the meeting point of complex human-nature relationships and storytelling practices. During her time at UCL studying the Masters of Ethnographic and Documentary Filmmaking, Mika turned her attention to language, identity and mythology, with a focus on small-town Japan and its unique folklore.