Notes in Poetic Practice — March 2023 to December 2024

18 March 2023

As things are always easier to work out on location, I decide to do a site visit of the Hague for the film1. Research online had given some sense of the Neo-renaissance architecture of the ‘Peace Palace’, though as I arrive and step off the tram, the domineering effect of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in its surrounding was palpable.

The tall entrance gates gave way to a view of the ornate building, held at a distance inside the compound grounds. Walking the gated periphery of the granite, sandstone and red brick building produced an uneasy feeling of being watched. This came either from the sophisticated camera system following my steps, or by the many hidden figures in the architecture, meant to evoke a feeling of justice and peace.

That day I discover that my trip had coincided with the announced arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin at the International Criminal Court (ICC), for war crimes in the Ukraine. Thinking on this, I run to meet Syrian friends protesting at the ICC against 12 years of violence in Syria, and the lack of legal unacknowledgement by the international courts.

I leave the Hague with a sense of frustration, being sure that I’d be stuck filming the periphery of the ICJ, its architecture, a space of unparalleled opaque technology.

20 November 2023

I continue the process of making work that tries to bring light and accountability to colonial violence. A violence too historic to be registered now by the law. At this time, in these days, the stakes couldn’t feel higher. Watching a genocide take place in Gaza, from the contexts that have long normalised these modes of ‘intervention’, always happening in other lands. It feels that there’s never been a bigger will for the technology of law to serve its purpose, and to bring justice.

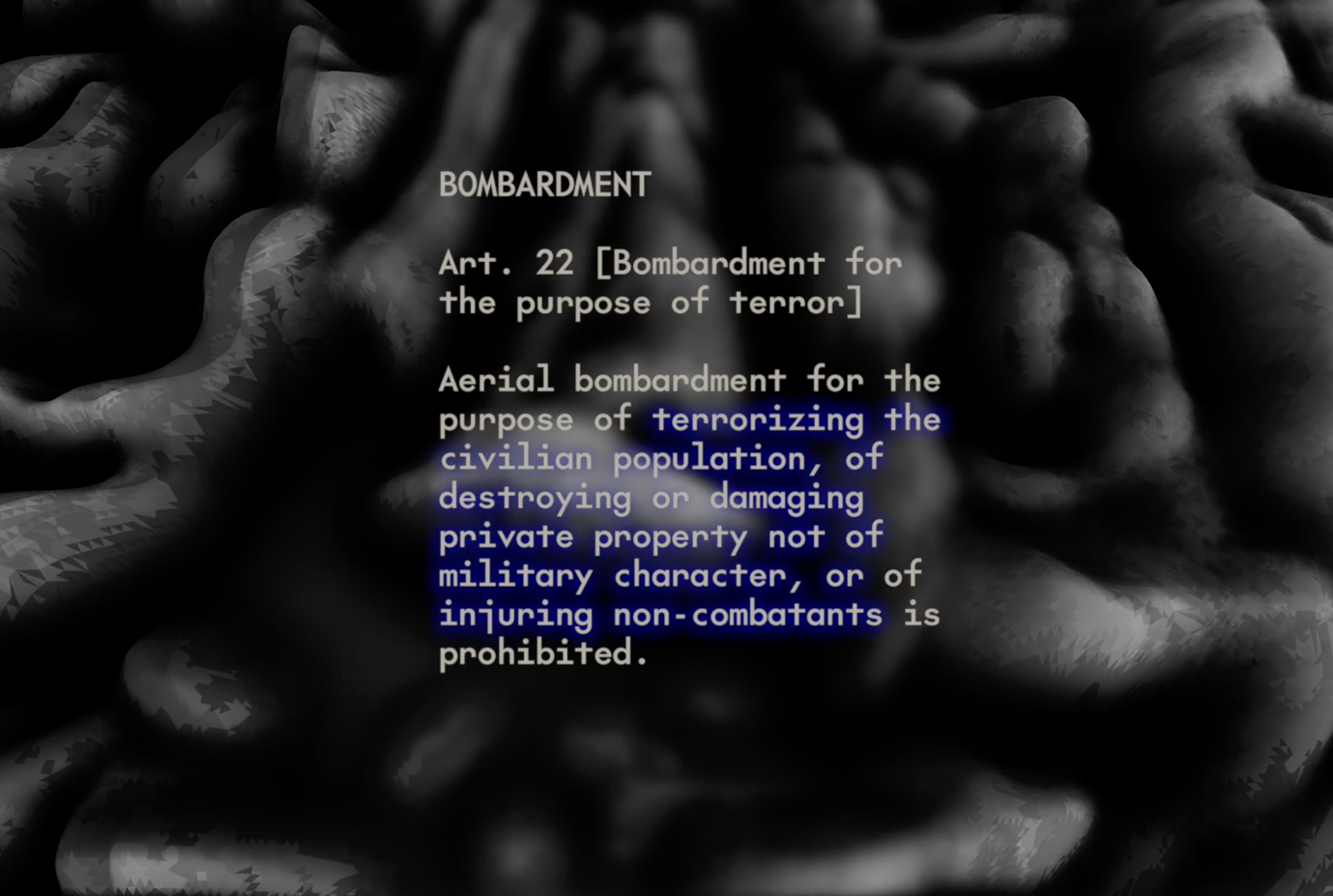

I continue to edit the film, which tells the story of the Hague Rules of Air Warfare written and negotiated in 1923 with the intention to control the use of aerial warfare as aviation becomes weaponised. A 100 years later, these as well as no other laws that strictly prohibit aerial warfare have ever been ratified.

11 December 2023

Many tensions exist across the field of law, divisions can be observed between those that believe in the function of a universal law for the good of all, versus areas of critical law that recognise its deep-held failings.

On my journey of interdisciplinary practice, I come to engage closely in conversation with the spaces of critical law. Because a law that doesn’t recognise its failings, rooted in colonial violence, is a technology not able to see violence or serve potential justice.

A central argument made in critical legal theory is that to understand its current failings, a historic turn is necessary in international law. This is outlined in legal scholar Anne Orford’s “International Law and the Limits of History” in The Law of International Lawyer. The proposition is that a crucial study of the colonial and imperial historic legacies ingrained in the law and its practice must be undertaken, to expose the coloniality of law’s authority. Legal scholars making this argument include but are not limited to R. P. Anand, Luis Eslava, Sundhya Pahuja, B. S. Chimni, Antony Anghie, Ratna Kapure, Vasuki Nesiah, Anne Orford and Rose Parfitt. Building further on this with feminist and intersectional thinking also from Emily Jones, Gina Heathcote, Sara Kendall and Yoriko Otomo.

By asserting the need to examine the historical processes responsible for inequalities produced through law’s enforcement, such ideas come to challenge law’s defining principles. Critical legal scholars argue that colonial biases and hierarchies remain deeply embedded in the institutions of international law. Efforts to ignore or suppress such legacies only serve to replicate and exacerbate the ongoing effects of colonial systems.

Building on this—I slowly shape a methodological framework of poetic testimony: the necessary engagement with radical forms of poetics in expressing and translating the experience of violence. In this, I draw on the etymological root of poiesis from the Greek term meaning to make. This alludes to processes building on and from an experience, both as a necessary development of its becoming, and as testimony.

The need and reason for giving testimony does not only reside in the spaces of law. The use of both poetic or forensic methods in response to tracing the effects of violence should neither exclude nor lessen the credibility or necessity of one or the other. This argument becomes particularly crucial in conditions where the perpetration and impact of violence is undeniable, yet scale and temporality make direct causation difficult to determine. Or when the corruption rooted in international legal systems doesn’t allow for the criminalisation of violence, as often seen in aerial warfare.

I make this argument partly in the knowledge that a law that accepts the importance of different evidentiary modes, is a law irrevocably changed.

But what if it is the hope in such a technology that is keeping us, now and always, in a cyclical state of violence?

26 January 2024

Today, judges at the ICJ ordered the state of Israel to take action to prevent committing acts of genocide in Gaza. This is following a case being brought forward by the South African state. Listening to the ruling brings waves of different emotions.

The ruling didn’t call for a permanent ceasefire. Though a promise of sorts is made to keep close observation on Israel’s actions. This not a strong enough ruling. Yet I do feel surprised and even slightly hopeful that such a clear argument was vocalised and televised in such an institution.

We will a law that works with all our hearts. Yet with all the will in the world, with all the evidence being televised and streamed daily, save for these small hard-fought moments of moral clarity, it seems to fall painfully short.

20 October 2024

In Recognising the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative, Isabella Hammad writes about how “fiction uniquely deals in subjectivities, in unstable narrative knowledge, in the limitations of perspective, and how different limited perspectives interact”. But goes onto reflect that she feels compelled to make this argument because she writes about Palestine.

In connecting law and poetics, an attempt is made to create a hospitable space of translation. Though not without its tensions. How to translate to be better understood? Or rather how to translate to communicate and build indescribable knowledge.

21 November 2024

An arrest warrant was issued today at the ICC for Benjamin Netanyahu and Yoav Gallant for crimes against humanity and war crimes, committed in Gaza between 8 October 2023 and 20 May 2024. Questions immediately arise about whether this means that international states have an obligation to carry out such an arrest if either of them enter their countries. The French government quickly makes an argument against needing to do so.

This legal gesture feels so small in response to what is taking place in Palestine, Lebanon, Syria and beyond.

8 December 2024

We woke up this morning to the news that the Assad regime had fallen in Syria. A moment of victory for those that have fought hard against this violent regime for so long.

Reports outline that Assad has left Syria and is taking refuge in Russia, but what of the war crimes and the decades of oppressive violence he’s led?

Law touches us all differently. Some feel its protection. Some feel its shadowy underbelly. Its intention of opacity is purposeful. We are meant to be kept in the dark, held at a distance, in a state of hopeful confusion. This holds a system in place, a status quo. A system that surely can’t remain as it is, or persist unchanged.

Endnote:

- The film I’m referring to is Frame of Accountability, 1 hour, Helene Kazan, 2023. For more information about this project:

http://www.helenekazan.co.uk/frame-of-accountability.html

Helene Kazan is an artist and writer. Drawing on feminist methods, Kazan’s work explores the use of poetics in expressing and translating the experience of violence. In investigating the colonial foundations of international law and its ongoing violent impact, her work privileges embodied knowledge in the form of poetic testimony. A process that looks towards expanded frameworks of reparative justice, in interaction and recognition by the law and beyond.

Kazan’s work has been exhibited and published across international institutions including: Sharjah Biennial 16 (2025); RADAR, Loughborough (2025); KARST, Plymouth (2024); Beirut Art Center (2023); e-flux (2022); maatEXT & Art Jameel, Lisbon (2022); Ashkal Alwan, Beirut (2019); Vera List Centre, New School, NYC (2018); Serpentine Gallery, London (2017); Tate, London (2015) and the House of World Cultures (HKW), Berlin (2014). Kazan is a Senior Lecturer in Fine Art at Oxford Brookes University and received her doctorate from the Centre for Research Architecture, Goldsmiths, University of London (2019).