Introduction

A few weeks ago, writer and translator Yasmine Seale suggested that I think about my translations as words overheard, as if a fleeting, serendipitous encounter. This felt refreshing, even liberating—the idea of translating between languages, of doing justice to a text is a heavy responsibility—even at times, a weight. But the lightness of the suggestion betrays its poise and perceptiveness. A reminder of sorts that there is no such thing as fixity, that certainty, too, is short-lived, passing.

When I was invited to guest edit this edition of Non-Fiction Journal, my thoughts immediately turned to the poetry that has long provided compass and solace for my work in the creative space—as a translator, as a poet, and as a film producer and curator. These hats might appear to be very different, but they are all facets of the same kind of quest, I feel—leaps of faith, questions posed to a world in constant flux. I understand documentary to be a process of translation in time, ideas, energies. Long before being a one of my ‘jobs’, translation was the prism through which I—like all migrant children—saw the world. It carries ambivalence and ambiguity close, a perpetual process opening and closing the possibility of holding several truths at once.

A fable that I often come back to when reflecting on the ways in which we tell the world is the story of the elephant in the dark room—a story recounted by Mawlana (Rumi) amongst others, in which a number of people find themselves in a dark room conscious of the presence of an elephant—something they cannot see, and yet sense and attempt to grasp. Each person touches the elephant to better understand what it is. For one, an elephant is something large and solid like a tree trunk. For another, an elephant is more like a pipe. And for another, an elephant is like a leathery flag. While they share their perceptions with each other, their understandings of ‘the elephant’ differ significantly and yet, they are all relaying facts and are all telling the truth. This fable has always represented to me the fact that reality is too large to make sense of, and that our individual stories give it form.

Last summer I reached out to a friend who was visiting his recently displaced family, six months after their home had been destroyed in Gaza. He wrote to me: “I am spending time with my parents… which is good but also strange… we try not to speak about the elephant in the room”. It was stirring to hear this reference to the ‘elephant’ that is the genocide, from him—from a perspective that understands the meaning of its violence more acutely than I can today, and yet cannot—for grief—grapple with its enormity. It underlined to me that my awareness doesn’t necessarily mean understanding or knowing. When I shared the fable with him, he thanked me for “the reminder that it is always our own realities that we investigate”. I come back to poetry for this foundational ability to interpret and to be re-interpreted. In his hands, the elephant had taken a new shape, yet it was also the same elephant, as ever imbued with a strong sense of memory and magnitude. I’ve known the elephant for decades, and yet from time to time, a door opens, and I understand it anew. It reminds me to resist the calcification of thought that comes with too much certainty.

In an interview with writer Linn Ullmann, the poet, essayist and translator Anne Carson shared a recent realisation: “I was just reading something about Descartes, and Descartes said this famous sentence “Cogito ergo sum,”—I think, therefore I am—which everybody knows and learns in school. But if you look at the sentence, really it says “Dubito, ergocogito, ergo sum.” I doubt, therefore I think, therefore I am”. She goes on to note, “Isn’t that surprising? I didn’t know it either because I never looked it up,” —suggesting, with wonderful humility, that it is one’s responsibility to do the work of learning. “Dubito has a bad press… that’s very provocative. Everything starts in doubt. Or it also could mean hesitation, it’s the same idea1”.

At an evening marking the 40-year anniversary re-publication of Edward Said’s seminal text The Question of Palestine, author Jacqueline Rose drew attention to the “question” in the book’s title: “As if to say there is always a knowledge to be pursued and we should never give up on that question, never close down the question of understanding, at the same time as the idea of the question of Palestine is a way of lamenting the invisible status of the Palestinians in Western thought. If the question is key, it is because for Said, language that tries to maintain its control over itself is part and parcel of the colonialist appropriation of the world, both word and world subject to false discriminatory imperialist mastery2”.

In documentary terms, this certainty, or veneer of control, is called “objectivity”. A variation of the fable suggests that the elephant finds itself in a dark room by design, specifically to disrupt and divide. Disagreements are inevitable if each person is so convinced of their truths that they can’t fathom anyone else’s… Who put it there?

A Bunch of Questions With No Answers is an ongoing project devised by Alex Reynolds and Robert M Ochshorn in May 2024 to filter out the answers in the US State Department daily news briefings, so that you only see/hear journalists’ questions—these becoming an insightful overview of the daily news3. The project underlines that for those of us who work with images, who dedicate our time to creating image-based work and curating conversations between images, the reality of the live-streamed genocide in Gaza brings everything into question. Have we done enough to underline the construct and choice inherent in all images? Is it finally time to let go of the ‘empathy machine’ analogy? What are our responsibilities as film workers now and for the future, of the form and of ‘humanity’? While there are pockets of defiance within the film ecosystem (the multi-faceted work of Film Workers for Palestine, for instance), the film industry at large has continued to evade (even, troublingly, to endorse) the vastness of the horror it is failing to name. Further, how is any image of Sudan still so far from mainstream screens? In October 2024, poet Momtaza Mehri reflected, incisive as always, “I would argue that the reluctance to name a thing a thing, to see what is happening in Palestine for what it is, begins with the disappearing of Africa from our imaginaries4”.

Our ways of seeing have been irrevocably altered. Perhaps, then, the questions we ask are more telling than the answers we currently have.

Non-Fiction Journal #7 was imagined from this space. A space of questions. Of in betweens. Of translation, alternative readings, what is said and what is gleaned. A space that understands ambivalence as a richness, as vantage point. That considers translation a form of communing, solidarity. Translation as hospitality, as Dhakar’s School of Mutants suggest. Hesitation as humility.

It has been a gift to have the opportunity to reach out to writers and artists whose work I deeply admire, and to reflect with and through them. While each contribution feels like a different part of the elephant, it has been wonderful to see the ways the pieces are in far reaching conversation with one another.

The journal’s cover image, designed by Golrokh Nafisi, offers a counterpoint reading to the way I have recounted the fable of the elephant above—it suggests that the elephant is in fact made up of people’s actions. We create our truths through our actions – some create with their hands, others with images, words, voices. Some create together, others building on the imaginaries of energies past and future. If the dark room is a space of division, the way out of it is through communal action, with intention and shared agency… recalling the words of luminous Ahdaf Soueif who, closing the Palestine Festival of Literature event in honour of Edward Said (referenced above), gently reminded the packed audience that being present in the room was merely a ‘prelude to action’ rather than ‘action’ in itself; she went on to share a phrase that Said was particularly fond of, by poet Grace Paley: “the only recognisable feature of hope is action5”. 2024 ended with a sharp reminder of this – when, on the 8th of December, Syrians ousted the tyrannical Assad regime, sending an electric ripple of hope and possibility across the world6.

With hope in the heart and action in mind, artist Barby Asante contributed a grounding ritual to the journal. I particularly love this for its centring of breath, and its invitation to pause before delving in. Poetry is an age-old practice of mapping breath with words. I have long carried the knowledge that my name means inspiration, but I only recently realised that inspiration is not only an aspect of the mind but also a function of the body—of breath. It is a reminder that the radical imaginaries we might bring into being move from the body to the mind and back… What is spoken and what is contained in the liminality between languages is at the heart of Mika Ogai’s beautiful film Glossary of an Empty Orchestra (鏡花水月); microphone in hand, the safe space of a karaoke room might just provide a portal… Struck by the wide use of translation in the June 24 protests in Kenya, poet JC Niala conjures a scene from a protest meeting, contrasting the breadth of language/s with the limited optics these protests are understood through globally. Poet Momtaza Mehri reflects on legibility, opacity and the thorniness of translation through the prism of South African photographer Ernest Cole’s work, recently the subject of several exhibitions and a film. Artist Helene Kazan shares a field diary of notes from March 2023 to December 2024, reflecting on the law as a flawed framework of accountability against the compass of feeling. Curator Abiba Coulibaly considers the limits, deceit and sharp edges of language in colonial contexts, as observed in Ousmane Sembène and Thierno Faty Sow’s seminal and recently restored Le Camp de Thiaroye, which recounts the mass killing of West African tirailleurs (who had fought for the French against Nazi Germany) by French forces in November 1944.

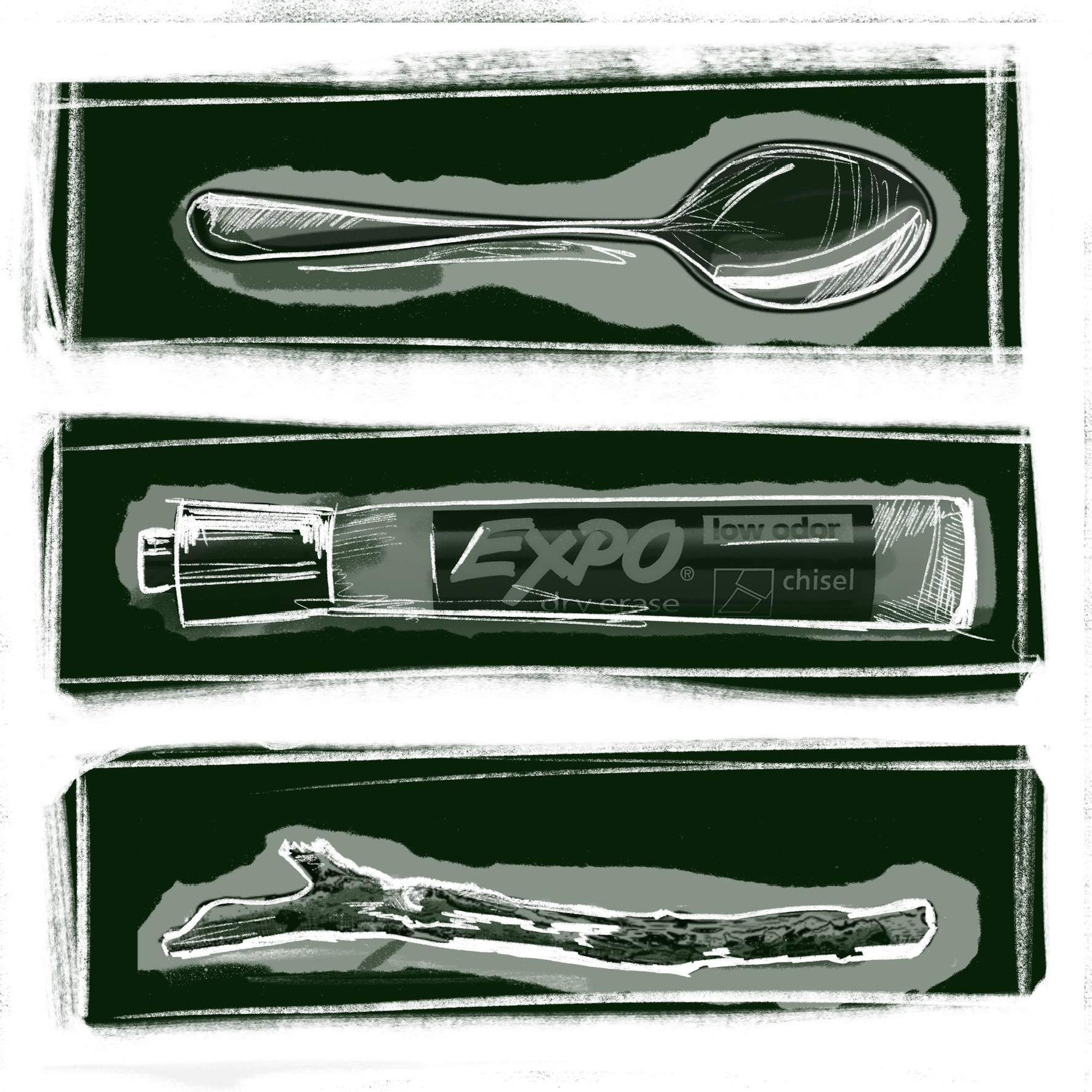

I am grateful to artist Mouna Kasa for allowing us to reproduce her brilliant illustration ‘By Any Means’, an homage to the steadfastness of Palestinians surviving occupation and ongoing genocide, fighting daily for the mere dignity of living – from the Palestinian children who defy drones with sticks, to the six Palestinian prisoners who dug their way out of Gilboa prison in September 2021 using a ‘rusty spoon’. Shortly before he was killed by Israel on 6th December 2023, much loved poet Refaat Alareer stated in an interview: “There is no way out of Gaza. What should we do… drown? Commit mass suicide? Is this what Israel wants? And we’re not going to do that… I am an academic, probably the toughest thing I have at home is an Expo Marker. But if the Israelis invade us, if they barge at us, open door to door to massacre us, I am going to use that Marker. Throw it at the Israeli soldiers, even if it’s the last thing that I will be able to do.”

I am grateful also to Carol Mansour and Muna Khalidi for the use of an image of therapist Leila Atshan’s hands, filmed in Beirut, as she explores the “window” Tatreez embroidery through touch, from their film Stitching Palestine on the Non-Fiction homepage. Tactility felt central to all contributions; while the journal exists primarily online, and the internet acts as a crucial connecting space, it felt important to recognise that we must also gather and build agency in the tangible world, and so there are two translations of the journal into physical form. Artist Emma Cheung has designed a riso-print-ready version of the journal that we hope will activate alternative distribution networks through the possibility of printing the journal cheaply anywhere (that has a riso printer) and by anyone who is keen to further disseminate our collective words. In its ability to print at scale cheaply, riso is a form of printing often used in collective spaces – community centres, schools, movement building spaces; it is concerned less with the means available than the message that needs to be conveyed. Similarly frugal but expansive, and responding to poet So Mayer’s brilliant alternative reading of film history through textiles, from tatreez to protest banners, artist Jenny Clarke has created a multi-panel piece made out of foraged cyanotype fabrics and that will travel between different hands over the coming months, complicating the idea of possession and embodying a question around how to collectively hold an artwork (we welcome suggestions, including from spaces who’d like to host it). Finally, writer and cook Melek Erdal ushers us into the folds of Hızır Gecesi, an Alevi Kurdish tradition of intention setting and sharing food in community, an invitation to gather, to remember that together we can bring light just as the days extend with the promise of spring.

Thank you for spending time with our wanderings and wonderings. As a new (Gregorian) year begins, I hope that these words land where they’re needed—digitally, physically, and spiritually. Recalling, with gratitude, the words of the late Nikki Giovanni (1943 – 2024) a poet who understood her words as action and used them with fierce intention, always:

I offer no apology only

this plea:

When I am frayed and strained and drizzle at the end

Please someone cut a square and put me in a quilt

That I might keep some child warm

And some old person with no one else to talk to

Will hear my whispers7

Endnotes:

- Writer Anne Carson: Life is Not Fair | Louisiana Channel, interviewed by Norwegian writer Linn Ullmann in September 2024: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rwkd8YDM6NY

- 2. Edward Said & The Question of Palestine | The Palestine Festival of Literature and Fitzcarraldo Editions at the Southbank Centre, November 20, 2024: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hPWiBgbkSJ8 [my punctuation]

- You can watch the daily briefing on the site, or there is an irregular email dispatch of questions—45 questions pop up on one day, 56 on another, or 29 questions that each reveal significantly more than the answers do.

- “Message, Received” by Momtaza Mehri, published Oct 15, 2024: https://bynoway.substack.com/p/message-received?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=668589&post_id=150270886&utm_campaign=email-post-title&isFreemail=true&r=6w8eu&triedRedirect=true

- Edward Said & The Question of Palestine | The Palestine Festival of Literature and Fitzcarraldo Editions at the Southbank Centre, November 20 2024: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hPWiBgbkSJ8

- I must note that this was made bittersweet by the (well known) brutality of the regime’s prison systems, the many lives it has claimed over the years and the (well known) prevalence of forcible disappearance under tyranny – a vicious weapon, locking families into the limbo of terror and unanswered questions across generations. To learn more, follow and support the work of The Syria Campaign, NoPhotoZone and Action For Sama. This is the subject of The Disappeared: The Case Against Assad by Sara Afshar, as well as Ayouni by Yasmin Fedda.

- Quilts by Nikki Giovanni, https://poets.org/poem/quilts

Elhum Shakerifar is a London-based poet and translator currently working on translations of Parinaz Fahimi’s works, for which she was a virtual translator in residence at the National Centre for Writing in 2024. Her translations also include English PEN Award-winning, Warwick Prize-nominated Negative of a Group Photograph by Azita Ghahreman, alongside poet Maura Dooley (Bloodaxe Books, 2018); the poem “A Glance” was a June 2024 Poem on the Underground. She is part of the 24/25 Southbank New Poets Collective. Elhum is also a BAFTA-nominated documentary producer; her credits include A Syrian Love Story (2015, Sean McAllister), Of Love & Law (2017, Hikaru Toda), Even When I Fall (2017, Sky Neal & Dara McLarnon) and Ayouni (2020, Yasmin Fedda). She is Executive Producer of Helene Kazan’s multi-sensory investigative tribute to Asmahan, Clear Night (2025), and is currently producing films by Ana Naomi, Brett Story and Mohamed Jabaly. As a curator with particular interest in film from the SWANA region, Elhum has curated for London Film Festival (2014-21), Shubbak – festival of contemporary Arab culture (2015-19), Barbican (Poetry in Motion: Contemporary Iranian Cinema, 2019), BFI (Drama & Desire, the films of Youssef Chahine, 2023) and is on the board of the Palestine Film Institute, co-curating the Palestine Film Platform. Elhum runs the London-based company Hakawati (‘storyteller’ in Arabic) whose work you can follow at @TheHakawatis.

Golrokh Nafisi is a children’s book illustrator, animator, and puppet maker engaged in the contemporary conceptual art scene. In her works, she covers daily events, lives of ordinary people, and the politics of the societies she lives in.