A Genuine Intoxication – False Equivalence in Ousmane Sembène’s and Thierno Faty Sow’s Camp de Thiaroye

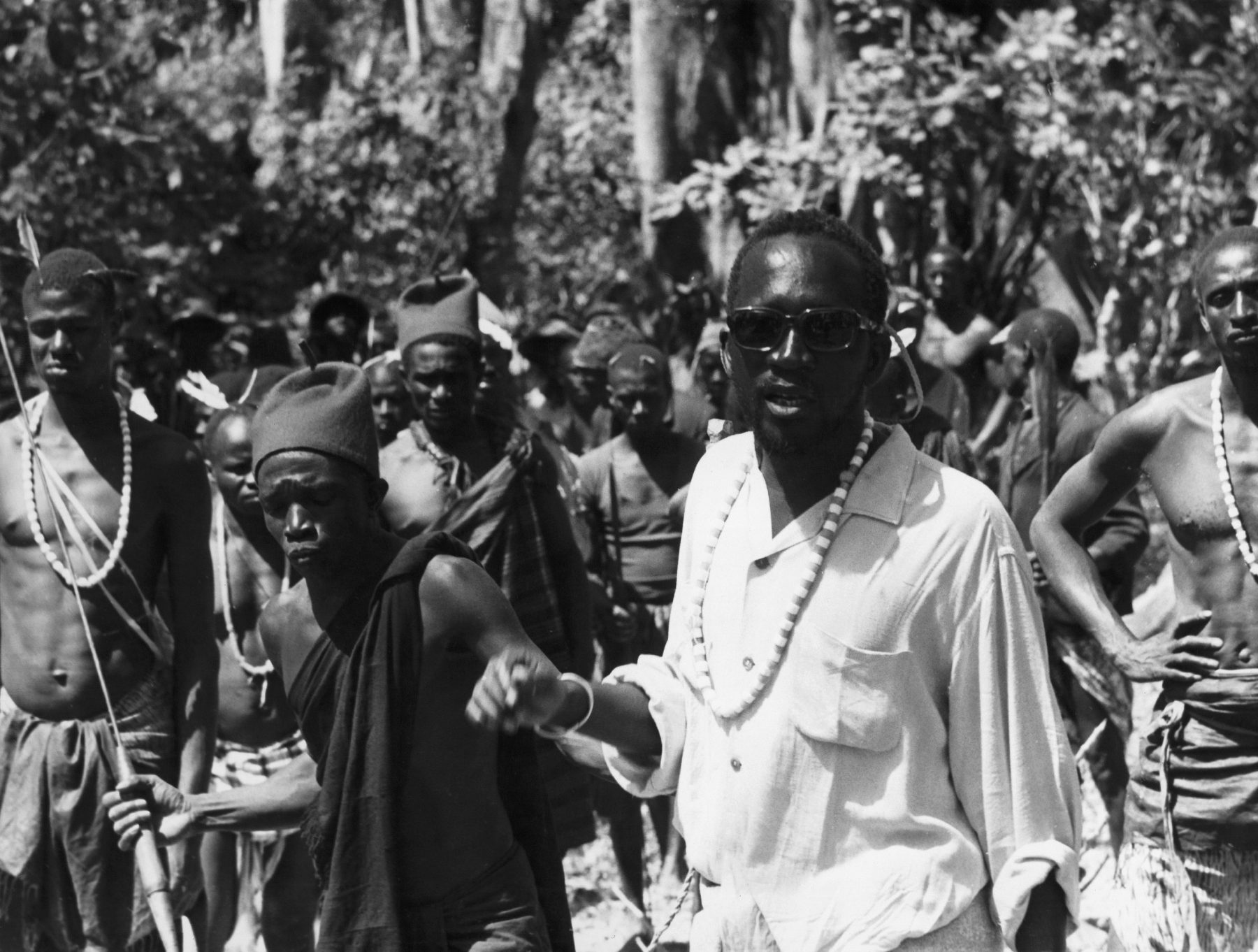

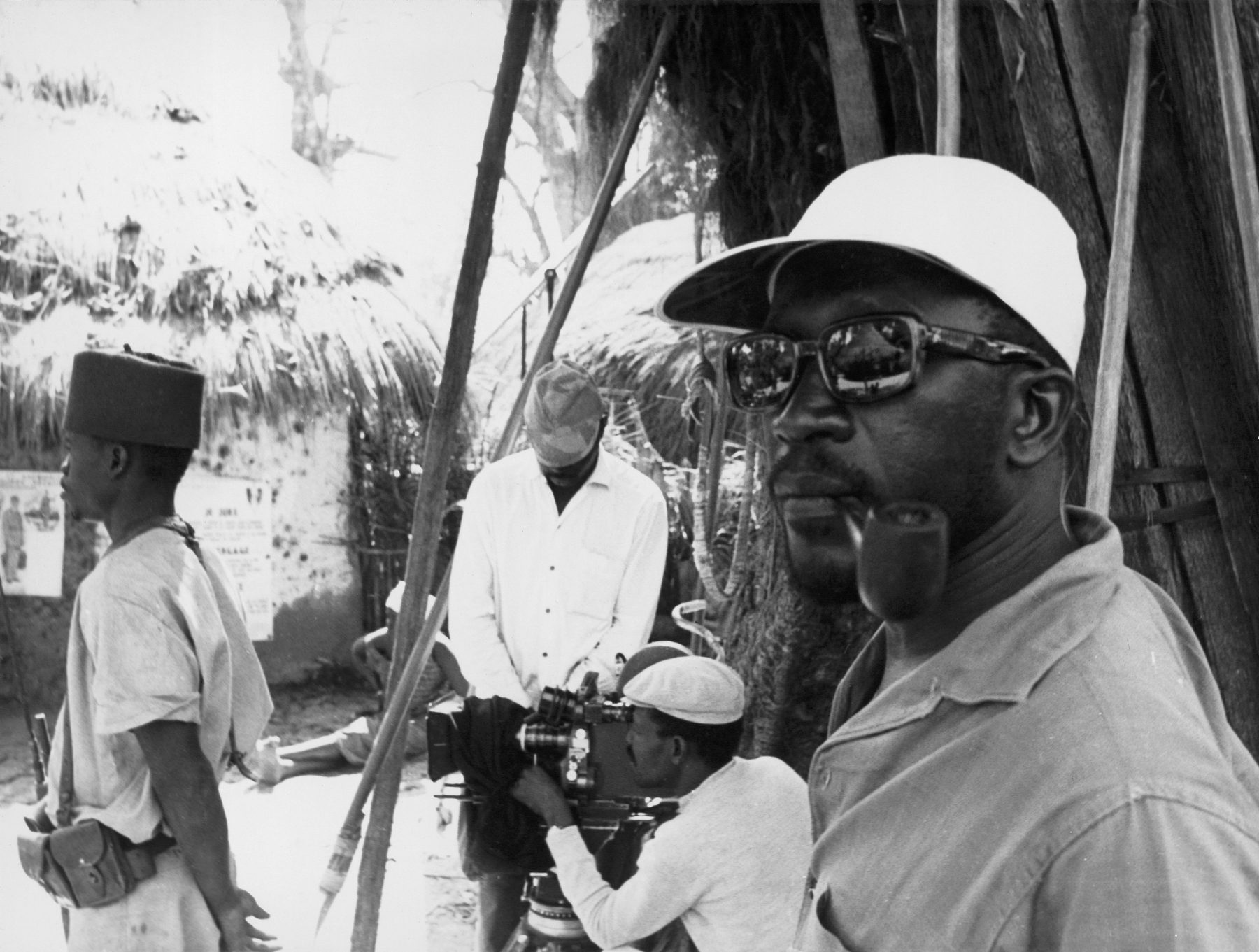

In the opening chapter of Black Skin White Masks, ‘The Negro and Language’, Frantz Fanon argues that the racialised and colonised subject will ‘be proportionately whiter—that is, he will come closer to being a real human being—in direct ratio to his mastery of the French language’, affording him ‘demigod’ status and ‘remarkable power’. This assimilation-by-imitation is what ultimately provokes contempt towards, and the demise of, Sergeant Diatta, the erudite and unwaveringly principled lead of Ousmane Sembène and Thierno Faty Sow’s Camp de Thiaroye (1988). Diatta commands a group of tirailleurs who have just returned from Europe where they fought (and provided pivotal manpower) with the Free French against Nazi Germany , and now wait in a transition camp—the eponymous (and existent) Camp de Thiaroye—days away from receiving their pay, being discharged, and returning to their homes.

For Diatta, native to Southern Senegal and possessing a flawless knowledge of French, mastery of the language proves to be a complication; it affords him power, but of the kind that is viewed as disruptive of a perceived natural order. If, as Fanon states ‘he will come closer to being a real human being—in direct ratio to his mastery of the French language’, being a ‘real human being’ represents a formidable threat: if a Senegalese man can be just as proficient at something as a French man—just as eloquent and deft when it comes to his ability to speak French—and further animate it with immaculate rhetoric and objectively superior moral arguments as Diatta does—the consequences are particularly grave, and underline a key tension and contradiction inherent to French endeavours of imposing a mission civilisatrice and later assimilation, both policies that have aimed to recreate French behaviours amongst non-French populations. Equal capacity demands equal treatment, Diatta argues; but for the White French soldiers who pompously marshal the desolate camp and the enticing streets of nearby Dakar, this understanding is not just undesirable, it is unfathomable.

Much of the film is about two almost synonymous processes: translation (a change to a different substance, form, or appearance) and conversion (to exchange for an equivalent), and their subtle differences, the degrees of flexibility and mutability that each allow.

The conversion of currency is of pivotal importance to the narrative. When paying the Senegalese tirailleurs, French generals insist on an exchange rate of 1000 French francs to 250 African francs (known as CFA, short for Communauté Financière Africaine) rather than the real value of 500 CFA. This raises the issue of the use of the franc as a currency across West and Central Africa3 The currency was first minted to facilitate the trade of enslaved Africans in the island of Gorée and is currently in use across 14 African nations, despite France abandoning the franc in 2002 upon entry to the Eurozone 4. This habit of short-changing and devaluing is recurrent in the coloniser/colonised dynamic and brings to mind the electoral system put in place in so-called French Algeria, effectively giving 1 European vote the same weight as 9 Algerian votes in order to render democratic independence impossible. With these systematic attempts to sidestep any semblance of accurate rates of exchange, all that gets lost in translation, or rather conversion, is indeed beyond words.

The value of life itself is also subject to barter within Camp de Thiaroye and is repeatedly invoked during the film in tandem with the phrase 5 ‘كيف كيف’. This is employed regularly at moments of cruelly false comparison, always in relation to (lack of) ontological parity between characters of different races. When the tirailleurs retaliate after American troops kidnap Diatta and take an American soldier hostage, they justify it as a fair retaliation. Their White senior tries to impress upon them that this exchange is not the same, given that their hostage is a White American, to which Corporal Major Diarra replies, both justly and, in this context, naively ‘noir, blanc, كيف كيف’. Similarly, when Diatta is returned, one tirailleur remarks on their stupidity for capturing a White American when it was a Black American who assaulted Diatta, to which another responds ‘no, White American, Black American كيف كيف’. Later, when, Groguet, an illiterate tirailleur, aware of his limited French uses ‘petit nègre’ to impress upon the general who controls their pay why it is that they merit fair remuneration, he evokes his experiences at war, including witnessing the bodies of massacred Jews in Europe, and concludes ‘white corpse, black corpse, كيف كيف’ in a plea for dignified treatment. Later, Capitaine Raymond, the sole conscientious French officer who argues for the tirailleurs to be paid what they are owed in full, reminds his colleagues that many tirailleurs and European soldiers spent years together as prisoners of war in concentration camps. The mercenary Capitaine Labrousse is quick to remind him that here, back in Africa, ‘c’est pas pareil’, a resounding retort that captures how the colonial administration truly feels in response to the tirailleur’s insistence of كيف كيف. These incantations of كيف كيف are the tirailleurs’ attempts to hold the French up to their revered pillar of égalité, in contention with the reality of its incompatibility with the racial politics and hierarchies that underpin the French Empire.

These contradictions, and the consequences of what really happens when the French are made to live up to their own standards, are perhaps most vividly described in C.L.R. James’ The Black Jacobins which details how the Haitian Revolution drew inspiration from the liberatory rhetoric of the French Revolution, resulting in the death of French plantocrats, colons and the system of chattel slavery they helmed. These same discrepancies are still playing out today when we consider the vile emptiness of Western-dictated international human rights law whose lack of enforcement reveals its performativity. At every utterance of ‘كيف كيف’, employed by the tirailleurs to substantiate the equality of humans despite race or rank, the actions of the overseers of Thiaroye respond resolutely, that their lives are not in fact of equal worth.

The forms of translation in Camp de Thiaroye —of experience, of monetary value, of language—converge in the sequence in which Diatta visits nearby Dakar, stopping at a brothel, where he has merely come to indulge in a glass of Pernod. Initially, in his second-hand US Army uniform, he is assumed to be African American, in response to which the personnel decide to double what he’s charged. Upon realising he is African, he is descended upon by the Madame, a shrill vision of ostrich feathers and entitlement, who firmly assures him “No niggers here! There never will be!” seemingly oblivious to the fact that she is in the epicentre of Black Africa. In the background, we pick up murmurings around a transaction: “15 minutes isn’t two hours” grumbles a john who feels cheated while the worker complains that her client only has European money. “A fuck is a fuck. So what 1,000 French francs is 500 CFA” chides the Madame in response. Upon Diatta’s ejection, an African American soldier spots him, assumes he is American and orders him to “speak American”, demanding “no more of your shitty French”. The irony being that Diatta’s French (and English and Wolof) is flawless, and that American is not a language. Upon reconciling, the two Black soldiers—one American, one African—share a tentative moment of kinship, exchanging tales of their experiences in the military and hometowns. But how can Detroit compare to Effok, both geographically distant and genealogically entwined considering Detroit’s status as the America’s second blackest city, and the historic plundering of Senegambia’s population for bondage across the Atlantic? In Diatta’s disastrous foray into the city, the complexity and significance of the social construction of race becomes most clear when intersecting with the atavistic issue of who has access to white women’s bodies, and the fraught dynamics between African and Afro-diasporic communities, further demonstrating the absurd racialised power dynamics of which the camp acts as a microcosm.

…

In the face of all the embellished platitudes and linguistic backflips the French employ to confuse and contort meaning, it is Pays (which translates literally as “country”), a mute soldier, whose comprehension often trumps his peers. He has been left severely traumatised, after having been interned at Buchenwald concentration camp, as was the fate of an estimated 15,000 tirailleurs during WWII—with Black people viewed as racially inferior by the Nazis, many of the atrocities carried out during the Holocaust were first used earlier in Germany’s African colonies. Pays, though himself only able to communicate through sign language and grunts—at times resulting in the ridicule or exasperation of his colleagues—is often best able to read the veiled yet highly consequential interactions around him, allowing him to intuit and infer real meaning, despite both language barrier and mutism. Diatta, a step from smug with his faultless French—the compulsion of colonial subjects to meticulously refine and perform their formal knowledge of the language, embodies in the words of Fanon, ‘a case of genuine intoxication’—makes the mistake of extending a literal understanding to the remarks of the European officers and taking them at their word. Assuming it is something they will keep, his linguistic prowess fails him in true comprehension. As a character, Pays symbolises both the unspoken traumas of the thousands of Black soldiers and civilians interned by the Third Reich, and the limits and deceit of language when it comes to operating within colonial contexts.

The spectre of Nazism permeates the film, as the tirailleurs are quick to call out the fascist behaviour demonstrated by their superiors. One of the key, and unfortunately most topical, grapplings of this film is the revelation that to fight an anti-fascist war does not apparently translate to defending anticolonial politics. As France lay down its arms at the end of WWII, it promptly picked them back up to subdue revolution in Indochina and Algeria (continuing to do so in overseas territories such as Kanaky and Martinique today). And many of the tirailleurs who were sent by the French to fight Nazism were later deployed in combat against Algerian freedom fighters, as depicted in Med Hondo’s Fatima L’Algerienne de Dakar (2004). Le Camp de Thiaroye deftly articulates instances of Nazi collaboration that defined Vichy France, and accusations of fascism abound. At one point, desperate for excuses to avoid remunerating the tirailleurs, an absurd conspiracy emerges: they have been employed by the Nazis to destabilise the Empire. Then again this is nothing more absurd than the reality that men might be used as cannon fodder (tirailleurs were often purposefully sent on more fatal missions) and then refused their pay. In turn, the White French throw back the accusatory intended-insult of ‘communist’, deduced from Diatta’s love of literature. In one scene, a soldier searching Diatta’s cabin for incriminating evidence comes across his book collection and concludes ‘all intellectuals are communists’ and I am again reminded of Fanon in ‘The Negro and Language’:

‘When a Negro talks of Marx, the first reaction is always the same: “We have brought you up to our level and now you turn against your benefactors. Ingrates! Obviously nothing can be expected of you.” And then too there is that bludgeon argument of the plantation-owner in Africa: Our enemy is the teacher.’

…

In an early scene, one of the few in which literal translation is performed, Diatta acts as a translator between the Americans and French, as the only soldier with a thorough command of their respective languages. In response to the upper hand and seniority this affords him, an American officer concludes that the French have “lost the empire.” When asked what was said Diatta remarks ”nothing important” highlighting not just the mediatory, diplomatic role of the translator, nor Fanon’s correlation of Eurocentric fluency and power, but Sembène’s ability to reveal the double-edged nature of language, a tool of forced assimilation that the colonised then weaponise to expose and destabilise the hypocrisies of the imperial order.

Endnotes:

1. The term ‘Senegalese tirailleur’ referring to colonial infantry troops recruited by France from its colonies, is a misnomer, given that infantrymen came from the countries that comprised France’s West and Central African territories, including, but not limited to, Senegal. In the film, this is hinted at through the prevalence of characters known by the names of their country of origin—Niger, Gabon, Congo, Oubangui (present-day Central African Republic) —rather than a given name. Sembène uses this chorus of individuals to demonstrate the expanse of landmass France had colonised and the breadth of peoples who were obliged to adopt this non-native language to facilitate communication. Despite its inherently violent and inegalitarian origins, this en masse linguistic imposition can be subverted, as revolutionary Burkinabé leader Thomas Sankara underlined in his 1986 speech at the First Francophone Summit:

“Initially, for us, French was the language of the coloniser, the ultimate cultural and ideological vehicle of foreign and imperialist domination. But subsequently it was with this language that we were able to master the dialectical method of analysing imperialism, putting us in a position to organise ourselves politically to fight and win… French enables us to communicate with other peoples in struggle.”

Reference: Sankara, Thomas. [italicise] We Are the Heirs of the World’s Revolutions: Speeches from the Burkina Faso Revolution 1983-87. Pathfinder Press, 1987

For Sembène’s Pan-African cast, French—and its derivative ‘petit nègre’*—is employed as a tool of anti-imperialist communication and organisation, with colonialism’s indiscriminate homogenising across pre-colonial socio-cultural landscapes used against itself.

- ‘Petit nègre’: A patronising, broken form of French simplified for use in (particularly military) colonial contexts.

2. Mirroring Sembène’s own trajectory having been drafted as a tirailleur before voluntarily enlisting to fight with the Free French Forces.

3. This is a topic explored in Djibril Diop Mambety’s darkly satirical technicolour Le Franc (1994), and deconstructed in less abstract terms in Katy Lena Ndiaye’s recent documentary Money, Freedom, A Story of the CFA Franc (2022).

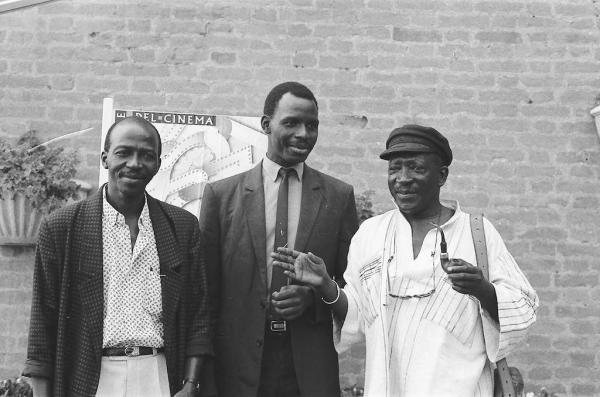

4. Notably, Sembène’s film sidesteps enduring French financial domination as a Senegalese-Algerian-Tunisian co-production, a rarity in the continent’s post-independence filmography in that it was made without European funding.

5.‘Kif-kif’: an idiom of Darija origin that has been adopted into French vernacular, meaning all the same, or like for like.

Abiba Coulibaly is a film curator with a background in critical geography. She programmes for Open City Documentary Festival, Film Africa and Magnum Photos Film Festival which she also founded. She has recently joined the Royal Academy of Art’s School of Architecture as an Associate Lecturer, continuing to combine her film practice with questions of spatial and civic equity after having founded Brixton Community Cinema and Atlas Cinema, two experiments in what democratising access to cinema could look like.