Un-Meshing The World

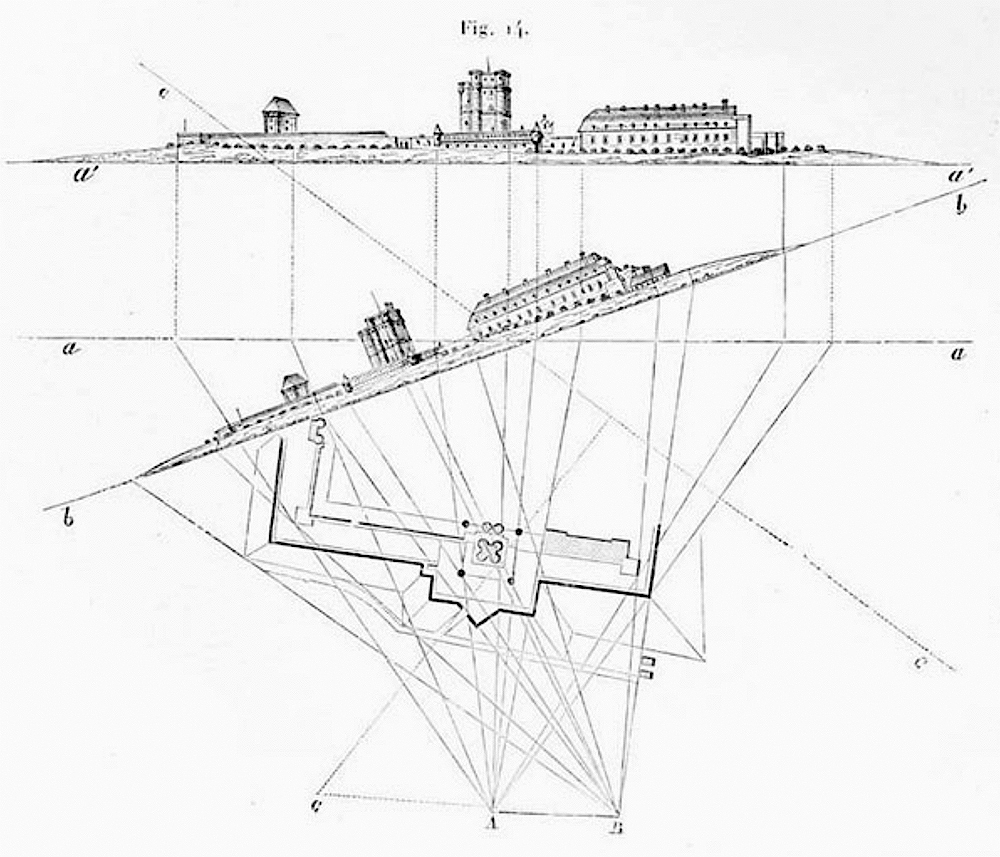

Two events occurred in 1492 whose repercussions are intertwined: the first being Columbus’s arrival on Turtle Island (North America); the second (and perhaps lesser accounted for) were Leonardo da Vinci’s supposed experiments with the “Magic Lantern”. Da Vinci’s device acted as a precursor to the projector. This allowed for the world to be reduced to a series of points and lines, to be interpreted and catalogued (“All things transmit their images to the eye by pyramidal lines,” da Vinci concluded)1. The experiments radically transformed rules of perspective and visual perception, acting as a key moment in the history of photography and film. Taken together, coincidentally or not, one can understand these two events of 1492 as inextricably connecting the advent of colonialism with image production—a connection that would ultimately extend to the violent dispossession of land, water, and natural resources of colonised peoples under “regimes of vision” through aerial mapping, surveillance, and visual reconnaissance.

When the British East India Company effectively gained control of the Indian subcontinent in 1757, one of the most pressing and immediate concerns was to begin mapping every inch of inhabited, cultivated, and forested land in Bengal. By the early 20th century, every village in India was mapped, documented, and catalogued. To map is to know, to fix, and ultimately to contain—nothing is allowed to remain hidden, unknowable, or opaque. Maps necessitate and visualize borders and act as manifestations of the violence required to maintain such delineations. Processes of colonial knowledge production seek to capture, silo, and define. Mapping creates a visible narrowness to which the map-territory relation is imposed. Lines created a priori to reinforce these structures are inherently non-neutral, and just like the borders they compose, designate an unnatural fiction separating belonging from un-belonging, citizen from non-citizen, human from less-than-human.

Photogrammetry, as its name implies, primarily uses photography, geometry, and triangulation as a means to accurately plot measurements of data to model a physical environment. As early as 1851 French inventor Aimé Laussedat saw the potential of camera mapping, and by World War I “terrestrial photogrammetry” was put into military use. Today, as the technology becomes increasingly accessible, everyone from architects, archeologists, and filmmakers are able to use photogrammetry as a tool to “uncover” the hidden spatial capacity of images. Recent experimental films like Hannah Jayanti’s Truth or Consequences (2020), Hsu Che-yu’s Single Copy (2019), Yun Choi’s Doomsday Video (2020), Sasha Litvintseva and Beny Wagner’s Constant (2022), and the work of New Red Order, Eva L’Hoest, Tivon Rice are just a few examples of artists and filmmakers experimenting with the possibilities of photogrammetry in non-linear and non-fiction storytelling, with various capacities and efforts to expand (or in some cases undermine) the “operational image”.

Organisations such as Forensic Architecture and SITU Research employ photogrammetry as an investigative method to help visualize and reveal war crimes, state-sponsored violence, and human rights atrocities globally. As photography grew increasingly affordable and accessible over time, the camera was used to reverse the colonial gaze by those who were never intended to wield it. Similarly photogrammetry offers possibilities of alternative horizons for seeing and thinking about the world—possibilities which offer the potential to invert and critique the very same colonial and imperialist formations that led to the invention of this technology in the first instance. The question then is not if, but how the repurposing of this technique of 3D mapping can be utilized to disrupt, muddle, or shift the trajectory of its origin.

Combined with LiDAR scanning (Light Detection and Ranging, a now common technology even included in the iPhone 13) one can generate a precision scan of any object or space from a handful of images. These images are transformed into a “mesh”, a sort of mosaic of images formed out of a “point cloud” model of data, stitched together to create a virtual replication of any space or object. Yet these images are not without their limits, despite their accuracy. What happens when the seams of the mesh begin to split, fragment, and untether? What happens when one searches for a complete image and only finds a void? Embracing this non-totality, I ask what it could mean to “un-mesh” the world.

_________

Beginning in Fall 2020, I started working on my third short film in a series of works about history, memory, diaspora, and decolonization – particularly in the context of political struggles in South Asia and the intersection of my own family’s biography. These films connect questions of cross-continental solidarity and ancestral kinship through a visceral mix of 3D renderings, desktop aesthetics, drone videography, 16mm film, direct animation and more recently photogrammetry and LiDAR scanning. Through collaboration with Sumedh Sawant, a young experimental animator and photographer based in Mumbai, we began to work on the film Golden Jubilee (2021). Initially, I reached out to him to help me create a virtual rendering of an ancient Goan folkloric spirit named Devchar, a tale that I first heard through my cousin. She claimed that you could hear this invisible spirit’s cane rattle throughout the villages at night, the spirit would help guide workers home who were lost in the fields. Sumedh was versed in a technique called “volumetric filmmaking”—a method to help build a 3D model of an object (or body) moving through time and space—which is how we ended up creating these uncanny 3D scenes of the spirit Devchar.

The film extends my practice and the work I have done with my father in earlier films. In Golden Jubilee I interviewed him about our ancestors, and his memories of growing up in Goa under the Portuguese, colonizers of the region for almost 500 years. With this film in particular, I asked my father to describe specific memories of growing up in our ancestral house in the quiet village of Curchorem in the South of Goa. In preparation for this, Sumedh and his team helped to scan the Sanzgiri ancestral house, creating a point cloud model and mesh of the building. Bringing the fully navigable 3D model of the ancestral house to my father, he began to inhabit virtual space and to narrate various memories that took him by surprise. I watched as he became engulfed by these distant thoughts of his childhood and family life in India, including a particular memory of meeting this spirit Devchar as a child himself. Eventually I would come to envision the Devchar as a sort of purveyor of the longue durée of Goa, walking through the ruins of crumbled colonial statues, churches, and villages in a digital imitation of how Walter Benjamin describes the “angel of history”—an imitation only enabled through this uncanny medium of photogrammetry.

As with all empires, the violence of colonial extraction remained essential to ensure the flow of resources, markets, and wealth from the Global South to the Global North. In Goa, this was primarily through mining and the mineral extraction of iron ore. After liberation in 1961, mining permits were turned over to local contracts with Goan businessmen, ensuring a quick transition of wealth from former colonial hands to the local Goan elite. Soon after, mining became one of the region’s most dominant forms of the accumulation of capital – almost as quickly as it began to devastate and destroy local wildlife and greenery. In an area once owned, tilled, and shepherded communally by all local people, the private ownership of collective land ensured the colonial project’s next evolution. Goa is home to one of the most bio-diverse ecosystems in the world—the Western Ghats. Mining permits were temporarily halted in 2018 following the hard work of environmental activists and human rights agencies, but the mining industries have lobbied hard and the mines are operational once again. This neo-colonial formation, one might observe, is perhaps best underscored by the mining industry’s widespread use of photogrammetry and LiDAR scanning as sources of continued extraction and surveillance. This practice is known as “prospective mining,” articulating a sense of “what might be mined”, establishing a future exhausted and foreclosed from any parcel of land as yet un-mined.

An overwhelming sense of ghostliness lingers throughout many of the scenes in Golden Jubilee, marked by the hauntings of the Devchar spirit, his spectral presence permeates the 3D photogrammetry scans of my family’s ancestral house. Practically, everything was just as my father remembered, the rooms, the kitchen, the bookshelves, and the prayer room were all in the same place. Yet something was off. The walls were fading, objects became transparent, cloth became translucent, shadows turned into voids, and photographs turned into a blurred mess of dots. The aesthetic latent in point cloud models, photogrammetry, and LiDAR scans presented an opportunity to embrace the void, the blur, the mess, the seams, the fragment, the gaps, the translucent, the split, the remnant, the incomplete, and the shard. Somewhere between reclamation and repair, photogrammetry offered a conflicted and contradictory vision forwards through a shared relationship between my father, myself, and his memories of our ancestral house and toward a sense of home and belonging despite (or perhaps in the face of) neo-colonial theft, destruction, and exhaustion. This vision was inherently incomplete and did not seek to find totality, nor its telos structured by a definitive whole. By working with—not against—photogrammetry’s limits, glitches, and blemishes (their artifacts as we say) we are able to touch on an approximation of a dark infinite—a reversal of this same tool’s use value as an instrument for hyper-accuracy—floating in a sublime nothingness only to reflect our faces back at us from the glare of the LCD retina screen. The lacunae of the image is perhaps our best chance to escape our already hyper-meshed world.

In Jorge Luis Borges’s famous one-paragraph short story On Exactitude in Science, Borges tells of an empire whose cartographers created a map on the same scale of the territory it measured, so much so that it covered the entirety of the empire. Future generations, Borges explains, lost faith in this map, leaving it to rot, exposed to the natural elements: “In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.” 2 Let us become those animals and beggars, losing our geographic disciplines, our exactitudes, and begin to un-mesh the world so that we might find ourselves in the incomplete voids of what might never have needed mapping.

1. Doyle, Frederick. “The Historical Development of Analytical Photogrammetry”, Photogrammetric Engineering, 259-265. 1964.

2. Borges, Jorge Luis On Exactitude in Science”, Collected Fictions, trans. Andrew Hurley. 1946

Suneil Sanzgiri is an artist and filmmaker. Spanning experimental video and film, animations, essays, and installations, his work contends with questions of identity, heritage, culture, and diaspora in relation to structural violence and anti-colonial struggles across the Global South. His work has been screened extensively at festivals and arts venues around the world. His first institutional solo exhibition Here the Earth Grows Gold opens at the Brooklyn Museum in October 2023. Screenings include International Film Festival Rotterdam, New York Film Festival, Hong Kong International Film Festival, Camden International Film Festival, Sheffield Doc/Fest, Doclisboa, Viennale, REDCAT, Menil Collection, Block Museum, MASS MoCA, moCa Cleveland, Le Cinéma Club, Criterion Collection, and many more. He has won awards at the BlackStar Film Festival, Open City Documentary Festival, Images Festival, Videoex, and other festivals. Fellowships and residencies include SOMA, MacDowell, Pioneer Works, Sentient.Art.Film’s Line of Sight, and Flaherty NYC. He was named one of the 25 New Faces of Independent Film in Filmmaker Magazine’s fall 2021 issue and was included in Art in America’s New Talent issue in 2022.