On Expertise

May 5th, 1923. The Dutch East Indies government celebrated the opening of a new radio station in the Malabar region of West Java. It was called Radio Malabar. In March 2020, the local Indonesian government began a plan to reactivate the station as a historical site and tourist attraction. My film Tellurian Drama (2021) imagines what would have happened in between: the vital role of mountains in history; colonial ruins as an apparatus for geoengineering technology; and the invisible power of indigenous ancestry. With narration based on a forgotten text written by the prominent pseudo-anthropologist Drs. Munarwan[1], Tellurian Drama problematises the notion of decolonisation, geocentric technology, and historicity of communication.

Whilst I was researching the film, a historian friend said that I should only look at the history of the site – Radio Malabar – through colonial archives. I was a bit doubtful as, for me, history is a methodological issue. If I was only to look at the history of Radio Malabar through colonial archives, then other imaginative possibilities could be missed or left unexplored. Whilst colonial archives are important, the Dutch government was an authority and I wasn’t really interested in how the authority documented what was deemed to be facts or non-facts. Instead my approach to history is to methodologically avoid any narratives presented by state representatives. I am interested in the point-of-view of non-main actors and in the concept of expertise drawn from other viewpoints. Trust in one’s expertise is earned, authority is imposed.

I was telling my historian friend that I was speaking with a park ranger in order to better understand the history of Radio Malabar, “an expert”, I said. My friend smirked and stated: “in this case, the artist should not be trusted as a maker of facts.” I agreed 100%. I added: “expertise is something with an objective position independent of societal prestige”. Authority and expertise are completely different concepts, unless an expert is themselves asserting authority.

Rachmat Maulana, the park ranger, is an expert whose words I can trust. He doesn’t dominate or assert any authority upon anyone. Rachmat Maulana is a person who inhabits the land where Radio Malabar was erected. Someone who engages and absorbs knowledge about Radio Malabar from his bodily experience; the landscape and his body have become one unit. I am interested in acquiring knowledge from a person who understands the landscape of Radio Malabar rather than from any authority figures such as the state, colonial government, scientific community, religious institution, etc.

My conversation with Rachmat Maulana is the backbone of the initial construction of Tellurian Drama. I am happy for this opportunity to share the transcript of my conversation with him archived in my research log while working on the film. This transcript is also an excerpt from the bilingual artist book Tellurian Drama, which is published by Jordan, jordan Édition in 2023.

FEBRUARY 15TH 2020

Many years ago, beyond the thick trees between Mount Puntang and Haruman, stood the most powerful arc transmitter in Southeast Asia. Today, one, two, three people are dancing enthusiastically in a heart shaped pool known as ‘the love pool’. Although now just a few pieces of rock ruin, Radio Malabar remains a resource of possibilities for experimental petrology studies.

It was the third time that I visited the colonial relic site of Radio Malabar. On a rainy day on Mount Puntang, I met a park ranger, Rachmat Maulana, who also owned a few collections of laminated photographs of Radio Malabar. He told me that he got them from a Dutch journalist.

Rachmat Maulana was responsible for the area around Mount Puntang and Haruman, including the remaining ruins of Radio Malabar. He worked for Perhutani [a state-owned forestry company]. He told me many stories— at the time I claimed to be a researcher from ITB [Bandung Institute of Technology]—about Radio Malabar and its micro histories. These histories seemed to be in line with a few notes by Drs. Munarwan, including his speculations and theories on the colonial legacy. Histories that I hadn’t found in any books, although Mang Yayang’s forthcoming book on the history of Radio Malabar would, according to Rachmat, constitute a more complete account of the project.

Our meeting was rather unplanned yet it became a vital to me in exploring the intricacies of Radio Malabar. Our conversation was recorded by ZOOM H6 at 1pm.

RACHMAT MAULANA (RM) : So, what have you actually found out about the history of Radio Malabar?

RIAR RIZALDI (RR) : Well, it seemed that the station was established to connect Indonesia to the Netherlands. And I’m interested in why the Dutch decided to build a radio instead of an electrical telegraph station. In fact, it was…

RM : de Groot? [Ir. Cornelis Johannes de Groot]

RR : Yes, exactly, he’s the engineer, right? It was de Groot who constructed the radio station and technology. From what I have read, the Dutch might have built a telegraph line instead but the line under the sea belonged to the British and, at that time, England held a monopoly on power in the south of the world. I’m also interested in the idea of two mountains as antennas.

RM : I haven’t read about the telegraph line.

RR: Yeah, the theory is that the radio was built because a telegraph wasn’t possible. It probably would have been cheaper to build a telegraph station but, perhaps because of colonial geopolitical reasons as well, it was the radio technology that was eventually built. The impetus was to connect the Dutch East Indies and the Dutch mainland as quickly as possible. By the way, the ORARI (Amateur Radio Organisation of Indonesia) people created a re-enactment of an early transmission experiment, from Malabar to The Hague.

RM : Yes, they’ll be another event like that soon, it’s usually held biannually. They mount the antennas to produce a live transmission to The Hague. In the past two years, the Minister of Communications and Information has come to observe. It looks like it’s going to become an official event, because the ORARI people (who are hobbyists) also want there to be some kind of museum here.

RR : [While looking through a few photographs] This the early poster of Radio Malabar? Hello Bandung, Dear The Hague?

RM : Yes, some time ago someone from the Netherlands was given a vinyl disc and 23 photos. Her parents [the person had the photographs] used to work here, accompanied by a lecturer from NHI [National Hotel Institute and Tourism] who seemed to be her colleague. She offered me the photographs and vinyl, but then they were borrowed by someone else and never returned. It’s the tradition around here, archiving is often badly organised.

RR They used to be at the Halo Bandung monument, right? Near the Istiqomah Mosque?

RM : Oh yes, the photos are there, although I haven’t seen them myself. They were borrowed by a writer who was working on a book about the history of Radio Malabar, but he wasn’t local to the region. The history is very confusing on the internet so if someone wants to do research they should speak with the witnesses first, our people who worked at Radio Malabar.

RR : Are many of the workers still around?

RM : No, no, they are all gone now, but they passed stories down to their children so they would know the real history. During the Japanese occupation, Radio Malabar was pillaged by neighbouring villagers from the mountain. They looted the roof tile, the steel, anything they could find, and have kept it to this day. It was not bombed like some people say that it was.

RR : Yes, many people say that it was bombed.

RM : No, it never was…

RR : But it was burned during the Bandung Lautan Api [Bandung Great Fire] [2]?

RM : Yes, it was burned during the Bandung Lautan Api. They [local people] were afraid that the radio would be occupied again, so they burned it down and moved to Jogja. This was during the revolution in 1946. Then Perhutani came in 1974 and planted the area with pine trees.

RR : So, no one was aware of the radio station before then?

RM : No one. It was discovered when the road was excavated.

RR : So it was a new discovery?

RM : Right, everything had been buried underground. The buildings, the technology… They found the ruins when they were starting to plant the trees,

RR : So the history had been lost?

RM : Yes, it was lost, and then rediscovered.

RM : After the land was cleared for planting, the area was converted into a camp site. Until now.

RR : But no one lives up here anymore, right?

RM : No, everyone moved away. At the time the Radio was burned there were people who lived in the lower area towards Palalangon, but there was no one who actually lived up here in the mountains.

RR : So the site was opened to the public in 1974?

RM : 1974 was the year the reforestation began. It didn’t open to the public until 1987.

RR : What are the main activities around here now?

RM : Hiking to Puncak Mega, it takes about 4 hours. There is an old Radio Malabar antenna tower up there. It stretches from here across to Haruman and Malabar 3.

RR : And how many years have you worked here as a park ranger?

RM : I’ve only been here for 3 years.

RR : Nothing existed before 1974?

RM : Yes, it was a forest. No one knew.

RR : So it’s only recently that people became interested in the ruins?

RM : Yes, there’s a lack of interest in learning about the history of technology. Most of the equipment used here was looted and donated to universities such as STT Telkom [Telkom University], but there is actually still a lot of equipment in the cave. The Dutch cave, up there.

RR : The Dutch cave? [3]

RM : Yes. the cave still exists, but it was walled by the Dutch because there is a resting area inside. And the cave also reaches Curug Siliwangi.

RR : But… there are accounts on the Internet mentioning, for example, that Radio Malabar was occupied by the Japanese.

RM : No, the Japanese have never invaded this area.

RR : When the Dutch were defeated, it was abandoned and then looted by local people. When did this looting happen?

RR : Between 1945 and ’46, since there was no station director or anyone responsible for looking after the station at that time. There were actually only 6 station Directors throughout its whole operation.

RR : From the time the station was established in 1917?

RM : 1917 was the start of construction, 1923 was the inauguration.

RR : Is it going to be made a protected area by Perhutani?

RM : A cultural site. It was taken over by the Bandung Regency. Disparbud [Department of Tourism and Culture] planned to make a replica of the station. The head of the tourism and culture office said that he would like to ask P.T. Telkom [4] to create a museum-like replica of the station. During his visit here, he mentioned that he wanted a complete building so that it could be rented out later.

RR : But it’s currently operated only as a camping ground?

RM : Right.

RR : You make profit from it?

RM : Right, we sell camping tickets and regular visitor tickets.

RR : The thing is that, for the history of technology in Indonesia, the existence of Radio Malabar is very important.

RM : But many people have forgotten about it. The interest at this point is almost non-existent.

RR : Are there not people who come here looking for wangsit [a search for the spiritual divine], pesugihan [the Javanese practice of money-making rituals], things like this?

RM : It’s quite rare

RR : It could be considered a sacred site.

RM : Here, in Caringin Block, under Mount Sebahu, it is said that the Dutch used to bury their treasure under that banyan tree. Some people believe that.

RR : What about Radio Malabar, does anyone believe that there may be treasure buried beneath Radio Malabar?

RM : There is a small group of people who believe that the radio signal still transmits from beneath the ground. There are also some people who believe that the radio signals still contain a certain power. But it’s rather confusing information, it’s hard to be clarified by science. Here [on Puntang Mountain], people still strongly believe in mysticism.

RR : Mysticism in the sense that people here still believe in the supernatural and put aside scientific facts?

RM : Right, and many campers have reported that they’ve witnessed something supernatural. Not everyone, but it happens quite often. It doesn’t bother me, it is just the campers’ experience, and since there are no permanent residents here, such things are hard to confirm, but it might be beyond my understanding.

RR : I happened to talk to a group of treasure hunters, most of them had no idea about Radio Malabar.

RM : Yes, the general public doesn’t know much about it because not so many people are taught about the history of Radio Malabar. And the history is so convoluted, there are many different versions. I’ve been thinking about how the iron and technological equipment in the old days was already very sophisticated. Especially Mount Puntang, which was a kind of community in itself with the houses and tennis courts…

RR : It was like a particular gated community for the colonisers?

RM : I think so.

RR : I’ve spent some time looking in Dutch libraries and museums for the Radio Malabar archives, but only a little.

RM : Right, the archives were mostly kept by those who used to work here and they are now scattered everywhere. Perhaps because of the effect of the gated community. Some hobbyists have some materials…

RR : Within the context of colonialism, these kinds of gated communities are found everywhere.

RM : But I think Radio Malabar was different.

RR : What can you tell me about the ex-Mount Puntang family?

RM : They were a group of families of former employees of Radio Malabar that later initiated a group in 1995. The history was mostly narrated by them.

RR : Most of them are descendants of the Dutch?

RM : Yes, indigenous employees at an administrative level were very rare so the group was indeed exclusive, but they know a lot of the history.

RR : Is the land here now owned by the state?

RM : Yes. It is all managed by Perhutani.

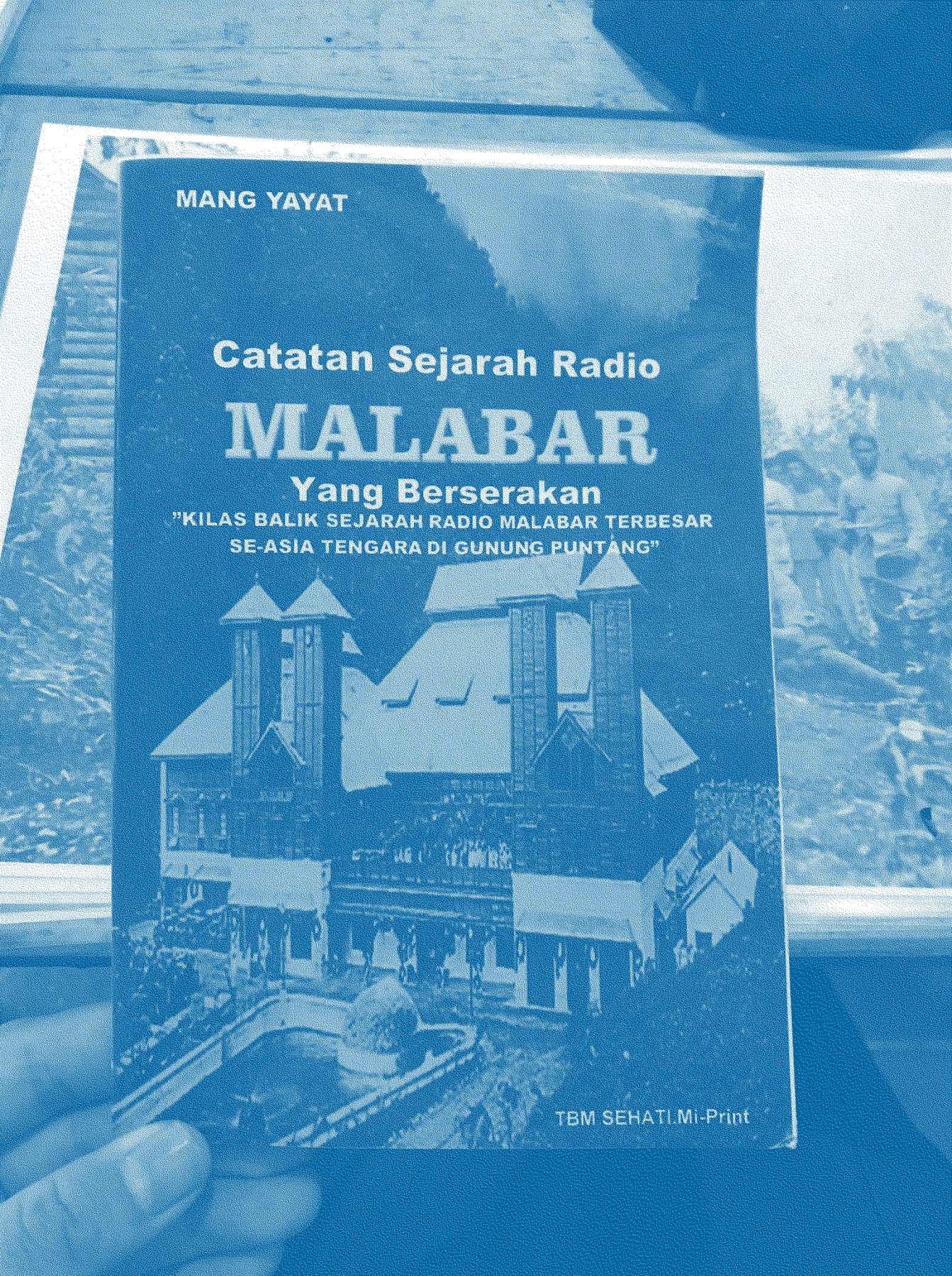

RR : [Holding a Radio Malabar book written by Mang Yayat] Who is this Mang Yayat actually?

RM : He’s an author. He’s one of the local people and is active in promoting knowledge. When he moved here, he wrote a book about the history of Puntang Mountain. There are a lot of things in the book that had never been discussed before, such as the mystical matters concerning Puntang.

RR : Oh there are myths as well, including a written record of Radio Malabar as the birthplace for Prabu Siliwangi [King Siliwangi]

RM : Yes, minor history

RR : This pool [the love pool] actually faces The Hague, right?

RM : Right. Some say something was planted in the love pool. Some sort of a signal.

RR : That suggests the technology is still being preserved down there in the pool?

RM : It’s still in there, and also beneath the building ruins. So a drone would not be able to fly across the building as the magnet is underground. If you were to try to take a picture with a drone, it would fall. It’s a strong magnet.

RR : Are people allowed to fly drones here?

RM : Yes, but the drone wouldn’t be able to reach the building. Even if it was directed to the building’s location, it surely wouldn’t work. Perhaps because the towers still have power. I have no idea about it.

+++

postscript from Riar Rizaldi:

This recorded conversation is the first time I had a conversation with Rachmat Maulana. After this conversation I conducted several interviews and exchange a great deal of information with him. Some says that Mang Yayat, the historian who has written the most complete history of the Radio Malabar site is actually a moniker of Rachmat Maulana. He doesn’t like Tellurian Drama though – for him: “it’s too fictional!”

_____________________________________

1.Drs. Munarwan was a pseudo-anthropologist and geologist who’s 1986 essay ‘Reconfiguring the Earth: Radio Malabar as a Geo-engineering Imagination’ explores how the earth could be geoengineered through the obsolete technology of Radio Malabar.

2. Bandung Lautan Api (Bandung Great Fire) refers to the deliberate burning of much of South Bandung by retreating Indonesian Republican troops during the Indonesian National Revolution. The tactic was intended to prevent military occupation by British forces that had earlier seized control of North Bandung.

3.The Dutch Cave of Puntang was a cave built by the Dutch on Puntang Mountain to store supplies during the construction of Radio Malabar.

4.P.T. Telkom is a state-owned telecommunications conglomerate, the origins of which were allegedly rooted in the establishment of Radio Malabar. Radio Malabar was not only a legal institution belonging to the state, but also an entity that drove the formation of amateur radio organisations in Indonesia.

Riar Rizaldi works as an artist and filmmaker. He works predominantly with the medium of moving images and sound, both in the black-box of cinema settings as well spatial presentation as installation. His artistic practice focuses mostly on the relationship between capital and technology, labour and nature, worldviews, genre cinema, and the possibility of theoretical fiction. His works have been shown at various international film festivals (including Locarno, IFFR, FID Marseille, Viennale, BFI London, Cinema du Reel, Vancouver, etc.) as well as Centre Pompidou Paris, NTT InterCommunication Center Tokyo, Taipei Biennial, Istanbul Biennial, Venice Architecture Biennale, Biennale Jogja, National Gallery of Indonesia, and other venues and institutions. In addition, solo exhibitions and focus programs of his works had been held at Batalha Centro de Cinema, Porto and Centre de la photographie Genève amongst others.