Looking for ‘lost’ archives

… so-called archive

has 2 floors

is set back on a busy road

is beside a river

has vast empty rooms surrounded by windows

has small rooms stuffed to the brim

has ordered and catalogued repositories

is full of decaying and rotting films

is semi derelict

is plagued by pigeons

is cold

is humid

will rot.

Poetry has long been used as a way finder, from the navigational poems of sailors to the oral mapping of indigenous communities in the Pacific. I was trying to find a building, one real — the former Nigerian Film Unit building on Lagos Island — and the other imagined — an exquisite corpse of my own doing that my film, a so-called archive, takes the audience on a tour around. I used these words to find my way.

I recently met the daughter of Kunle Akinsemoyin, co-author of seminal text Building Lagos1. This is a book which has recently recaptured the imagination as Nigerian colonial architecture undergoes a revisioning process through the lens of tropical modernism. I told his daughter excitedly about the time, years ago, when I looked up his book in the British Library in the hope of finding architectural plans for a building that had become legend. I described to her the scene: flipping through the pages hurriedly (a bad habit I have in archives), looking past sketches of Barclays’ Bank, buildings on the Marina, the suggested quarters for government offices, or renderings of the colonial classical style, to find the building. All to no avail.

I told her because the book felt rare and uncommon and when I held it in my hands I had imagined myself a detective on a trail (a fantasy I have as a researcher). I was searching for a building that I heard mentioned years before during a conference in Berlin.

A building that I went to Lagos to find when I visited unchaperoned for the first time in 2018.

A building I had played a game of telephone to locate, being passed on to different assistants, secretaries and area chiefs before finally gaining permission to see it, the day before I left.

A building that became the protagonist in the last film I was to make about colonial archives.

The Former Nigerian Film Unit

The Colonial Film Unit was the British Imperial visual propaganda program. The unit ran from 1932 to 1955 and was headed by William Sellers, a man who promoted a particular form of colonial filmmaking known as the ‘Specialised Technique’.2 This grammar of filmmaking was founded on his belief that colonial subjects, especially Africans, could not become cineliterate because of deficiencies in both their perceived intelligence and the physiological composition of their eyes. These ideas were not discredited until the winding down of the Colonial Film Unit in the 1950s and a field visit from an anthropologist who disproved Seller’s spurious assertions.3

After the end of the Second World War, the Colonial Film Unit diversified its output beyond explicit war propaganda. The unit made films both for a British public, in order to demonstrate the economic benefits of their investment in the British Empire, and for colonial subjects in order to instruct them into the British way of life. In expanding its scope, Colonial Film Unit outposts were established, in what was then the Gold Coast, Jamaica, India, and Nigeria.

The Nigerian Film Unit was created in 1947, first by training 3 local men in filmmaking, then through the development of sub-units across northern and southern British ruled territories. These sub-units were active in producing newsreels for local events and exhibiting colonial films through mobile cinemas.4 These mobile cinemas toured countries on vehicles, screening a selection of films made by the unit alongside a more commercial programme. It allowed for the distribution of films in both cities and more rural areas, screenings were accompanied with live translation in local languages. In 1959, in the run up to Nigeria’s Independence, the activities of the Colonial Film Unit were administered by the newly formed Federal Ministry of Information who created the Federal Film Unit, widely known as simply the Film Unit.’5

‘The Film Unit [was] a hangover from the colonial administration’ and produced largely the same content of newsreels, ‘…pedagogical documentaries…imperial spectacles…’ and narrative morality tales. The Nigerian Film Unit was staffed by Nigerian technicians, although led by British colonial functionaries they were trained primarily at the Overseas Film and Television centre in London which acted as a hub for cinematic education across the former colonies.6 7 These Nigerian operatives were trained in the style and production regimes of the Colonial Film Unit, of William Sellers’ ‘Specialised Technique’, of filming reality without camera trickery or movement – only the one to one exact representation of life to film.

After the Biafran War, and with the institution of the Second Republic of Nigeria in 1979, there was the need for a new body for national film culture to reflect the latest iteration of Nigerian identity. The Nigerian Film Corporation was created by a Nigerian parliamentary act and the newly formed corporation included: provisions for narrative filmmaking for the first time; the establishment of a national film school; dispensing financial assistance to Nigeria’s filmmaking community; and proposed plans for the National Film, Video and Sound Archive. This new archive was built in Jos, Plateau State. In the 1990s the films of the Nigerian Film Unit and the Federal Film Unit were transferred from Lagos to the cooler environment of the northern state which some locals called ‘Little London’ and thought better suited for the maintenance and preservation of a film archive. Film is usually archived in cold storage to prevent its deterioration and the humid climate of Lagos makes these conditions hard to achieve.

From the colonial to the post-colonial, to the national renaissance, the body making films about, and for, Nigeria changed its name, purpose and outlook – from Nigerian, to Federal, to National. At some point between 1947 and 1959 the Nigerian Film Unit found its home in a two-storey building on Ikoyi Road. Ikoyi road is on Lagos Island, one of the islands that make up the lagoon city of Lagos, the former capital of Lagos state. It is known for the Brazilian Quarter of Lagos, where those formerly enslaved returned to Nigeria after they achieved their freedom and resettled. They brought with them craft and building skills that were used by the new colonial powers to build government offices, government administrative spaces, and living quarters. These returnees also built their own houses using methods learnt in Brazil that would accommodate for the tropical environment.

I went on a tour of Lagos Island’s remaining colonial buildings during a 2018 visit. We began at Independence House, a ‘gift’ from the British on the eve of Nigerian independence. The concrete skyscraper rising erect and high above the traditional one or two storey buildings on the island, situated beside Tafawa Balewa Square, previously used for Empire Day celebrations and similarly unveiled and redeveloped on the occasion of Nigerian independence in October 1960. I was told that the building was abandoned in the 1990s and had remained unused until 2018 when the Lagos Biennial had reoccupied the site. I began to find these evacuated colonial buildings everywhere. Lying proud but empty of presence. Walking on Broad Street, the main

thoroughfare through old Lagos Island, I photographed the house of a Brazilian returnee. His name was carved in the facade and his descendants looked down at me from atop the balcony.

I don’t know the exact provenance of the building that I call the former Nigerian Film Unit and I never found it in Building Lagos, but I did get to go inside. On my last full day in the city, still unacclimatised to the humidity, and so revealing my not-from-hereness through the beads of sweat trickling down my face, I finally got to meet the Lagos area chairman of the Nigerian Film Corporation. We talked and he teased me about the sweating and educated me about the work of the corporation. I asked him to show me the former Nigerian Film Unit. He was surprised that I didn’t want to see the corporation’s new purpose-built cinema with air conditioning. I obliged him on a tour of the cinema, offices, conference rooms, and then we left the squat orange building of the Nigerian Film Corporation, through the back door and headed across the compound to see what I had come for.

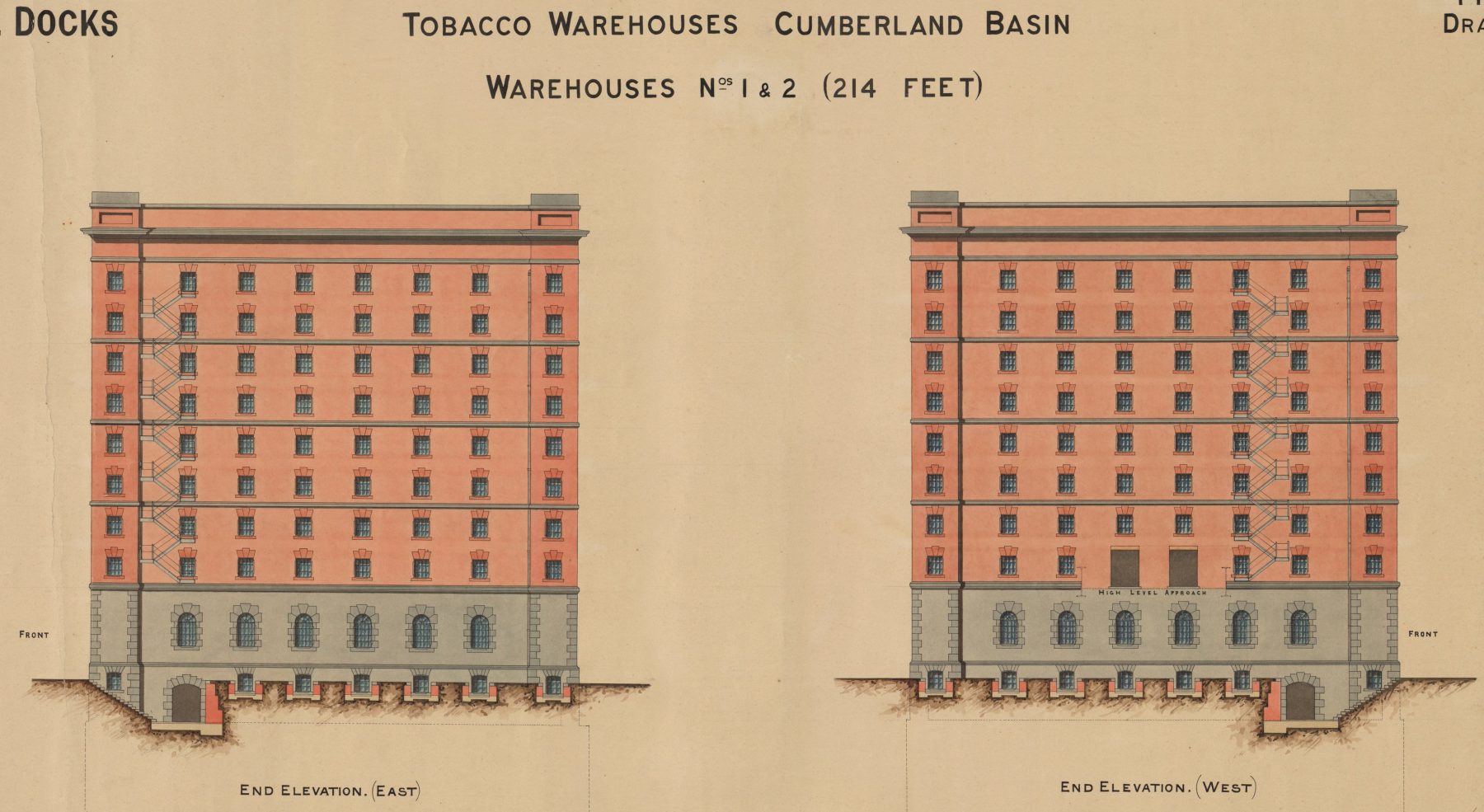

The former Nigerian Film Unit is a building paused. Stopped clocks, rusty film cans, fungus filled crevices, plant vines creeping up the walls, immovable broken Kodak machines, smashed windows and piles of cobwebbed files, are all that remain. It’s as if everyone who worked there left at once because there was an alarm, an emergency. There was an emergency, but no one ever called it that at the time. The building was a carcass that I could dream into, hollowed out and in the shadow of the new beginning that it faced, a face visible to the world. It reminded me of somewhere else. Of a building I danced in, on the empty top floor of a bonded warehouse in the Cumberland Basin, of the River Avon, Bristol.

A building that held sister films to the reels of film that I was not able to see in Lagos because of its condition.

A building I spent several freezing cold weeks auditing the film collection of the former Empire and Commonwealth Museum.

A building that had definitely been squatted and raved in.

A building full of bird shit and a heavy goods lift.

A building preserved, listed, and repurposed.

A building full of photographs, film and objects hoarded as part of the colonial spoils.

1Akinsemoyin, Kunle and Vaughan-Peters Alan, Building Lagos, F. & A. Services : Pengrail Ltd, 1977.

2 Sellers, William, Film for Primitive Peoples : A New Technique, London, Film Centre 1940, p.10.

3 Larkin, Brian, Signal and noise: media, infrastructure, and urban culture in Nigeria, Duke University Press, 2008, p.160.

4 Balogun, Françoise , The Cinema in Nigeria, Delta of Nigeria 1987, p.21.

5 Haruna, Emmanuel, [Interview], unpublished, 2018.

6 Balogun, Françoise , The Cinema in Nigeria, Delta of Nigeria 1987, p.21

7 Larkin, Brian, Signal and noise: media, infrastructure, and urban culture in Nigeria, Duke University Press, ibid. 2008..

8 Nkanga, Peter. “The Starting Point”. Souvenir of A Monument, 2011. 9 Akinsemoyin, Kunle and Vaughan-Peters Alan, ibid, 1977.9

9 Akinsemoyin, Kunle and Vaughan-Peters Alan, ibid, 1977.

Works Cited

Akinsemoyin, Kunle. and Vaughan-Richards, Alan. Building Lagos. 2nd edn. Jersey: F. & A. Services : Pengrail Ltd.1977.

Balogun, Françoise. The Cinema in Nigeria. Enugu: Delta of Nigeria, 1987.

Haruna, Emmanuel. [Telephone interview], 13 December 2018.

Larkin, Brian. Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria. Durham, N.C. : Chesham: Duke University Press ; Combined Academic distributor, 2008.

Sellers, William. ‘Film for Primitive Peoples: A New Technique’. Documentary Newsletter, 1940.

Onyeka Igwe is a London born, and based, moving image artist and researcher. Her work is aimed at the question: how do we live together? Not to provide a rigid answer as such, but to pull apart the nuances of mutuality, co-existence and multiplicity. Onyeka’s practice figures sensorial, spatial and counter-hegemonic ways of knowing as central to that task. For her, the body, archives and narratives both oral and textual act as a mode of enquiry that makes possible the exposition of overlooked histories.She has had solo/duo shows at MoMA PS1, New York (2023), High Line, New York (2022), Mercer Union, Toronto (2021), Jerwood Arts, London (2019) and Trinity Square Video, London (2018). Her films have screened in numerous group shows and film festivals worldwide. Currently, she is Practitioner in Residence at the University of the Arts London and she will participate in the group show ‘Nigeria Imaginary’ in the national pavilion of Nigeria at the upcoming 60th Venice Biennial in 2024. She was awarded the New Cinema Award at Berwick Film and Media Arts Festival 2019, 2020 Arts Foundation Fellowship, 2021 Foundwork Artist Prize and has been nominated for the 2022 Jarman Award and Max Mara Artist Prize for Women.