What is a good life? And who can have it?

Tongpan (ทองปาน)

Tongpan (1977) is a 16mm black and white “docudrama” following the story of a student activist from Bangkok who travels to Thailand’s Northeast – a region that has become synonymous with underdevelopment and poverty – to attend a seminar on the construction of a mega-dam project. Looking for local people to also participate in the seminar, the student meets a farmer who lost his land in a previous dam construction.

The film engages with a specific moment in Thai history, presented to audiences in the opening of the film:

On October 1973, a student-led rebellion in the capital city of Bangkok brought half a million people into the streets. For the first time in Thai history, working people reached for power.

A military junta fled into exile, and the students from the city went into the countryside to tell the farmers.

This film, conceived in the light of that October 1973 rebellion, is a re-enactment of actual events.

Tongpan was produced by the Isaan Film Group, a collective of student artist-activists formed around Paijong Laisakul, Surachai Jantimatorn and Euthana Mukdasanit from the leftist youth-counterculture movement at Thammasat University – Thailand’s second oldest university that was founded by Pridi Banomyong in 1932, two years after the Siamese revolution. The film’s production was halted when the filmmakers were arrested during the 1973 crackdown. It was later banned until 1978 for its socialist undertone, making it an easy target for accusations of communism. The film never received a theatrical release and instead entered into a network of makeshift itinerant guerrilla screenings, re-appropriating the spaces used by US sponsored screenings of propaganda films against communism.[1] Within this historical background of both national as well as international power configurations, Tongpan is today re-visited as an important document of Thai film history, not only for its content but also its dissemination, and ‘when we talk about political cinema Tongpan is the title that pops up’[2]

The film was conceived within the very short period of hope for democracy that followed the October 1973 student-led rebellion. After this time of democratic enthusiasm, there was a violent crackdown in 1976. “People from cities got interested in countryside stories and were realizing the social problems”[3]. On structural administrative levels, the promise and ideality of democracy was to be put into practice, translating into various attempts to include local stakeholders in decision making. The workshop to discuss the Pa Mong Dam project was one such attempt.

Attempts at crafting solidarities between the urban intellectuals from the capital and the northeastern farming populations were driven by an idealistic desire for equality and social justice. ‘Cinema became a carrier of ideals or messages, there was a shift from entertainment towards social values’[4] at a time when “no-one thought cinema could be carrier of social messages, especially with a Thai filmmaker”[5].‘Tongpan become the prototype for NGO or activist filmmaking, which did not exist much at the time’[6].

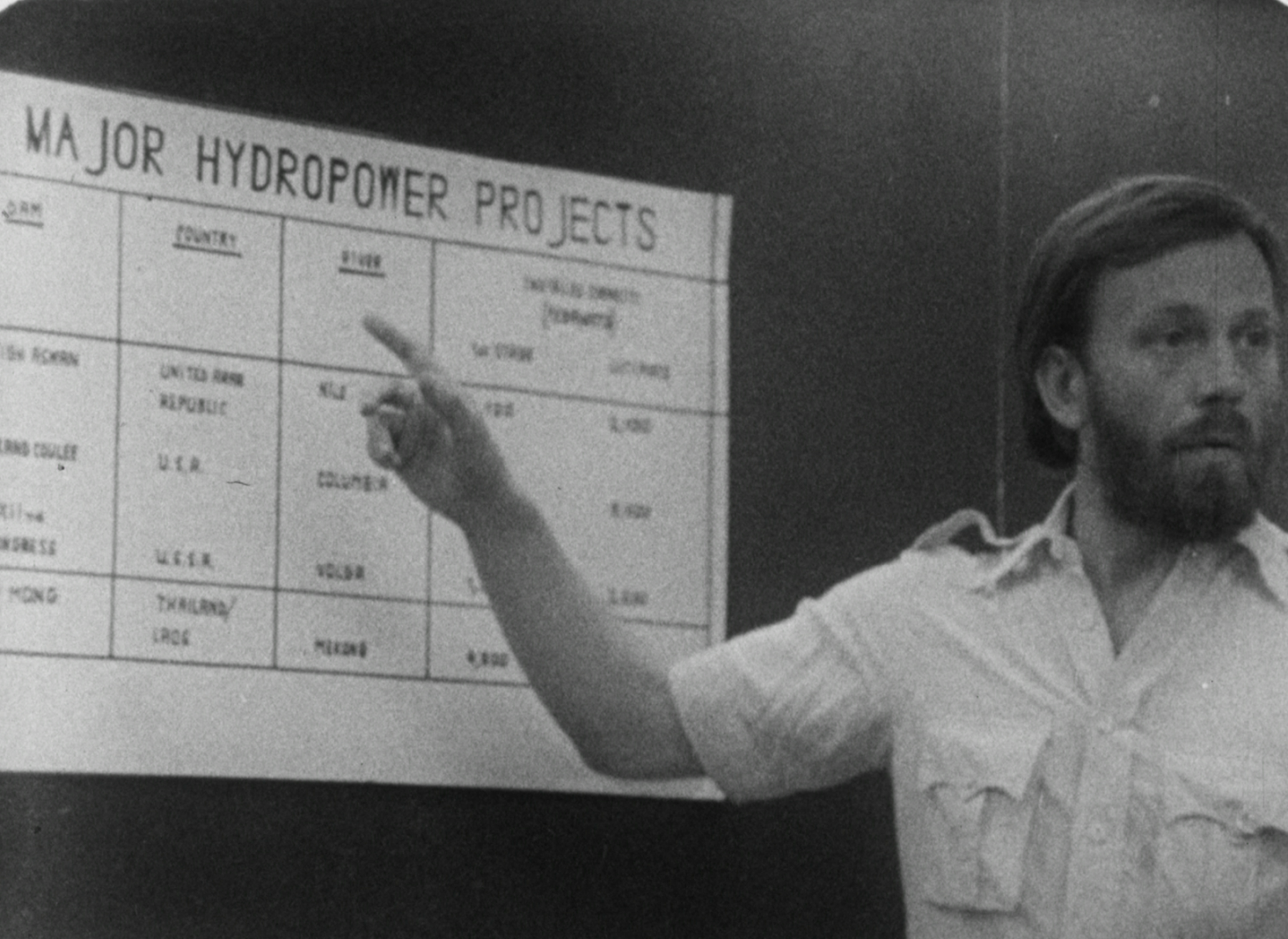

In the film, the space of the seminar to discuss the dam project with farmers is lauded as an “exemplary practice of true democracy”[7]. In its idealistic aspirations, a space where different stakeholders voice their concern and have a say in decision making. The leading Thai public intellectuals of the time, including artists and writers such as Sulak Sivaraksa, Lao Kamhorn and Khamsing Srinawk, appear in the film and articulate their positions in the seminar room:

It is always believe the experts.

Especially if they are from the West.

They want to make Thailand like the West.

To catch up with the Japanese.

To catch up to the foreign investments.

Development only serves a few people in Bangkok

Do we see the disadvantages of electricity?

Electricity brings radios and TV’s that tell people to buy things.

The Japanese and the farang industries just get richer

And what about the destruction of our country?

The whole province of Loei will be flooded by this Pa Mong Dam.

People will be homeless.

The temples destroyed.

The giant fish buk unique to the Mekong breeds right where they are building

the dam.

The buk will be extinct.

Are these experts farang interested?

Are people in Bangkok interested?

They might think it is trivial or of little economic value.

These loud and clear anti-colonial positions against the benefits of development sound very different from the Western excuse insisting that people from the global South “want” and “deserve” to follow the pathways of development. The company and governmental representatives perform their rotational jargon of development as the future and praise the potentialities of hydroelectric power. They demand to “help people to understand the national interest” and that “sometimes a minority has to sacrifice for the benefit of the majority”. As we are watching the world collapse faster than ever because of the promises of so-called Western development, such an assumption of detachedness, foundational to the delusional binary of “majority” and “minority”, has long been philosophically, ontologically and historically proven wrong.

Behind the banner of White Man’s “development” and hydroelectric power projects, what is actually discussed in this seminar room, is the question of better lives and who can have them.

A seminar participant sarcastically remarks:

In Chonburi.

We meet in a room like this decide the fate of the people out there.

The resort hotels in Pattaya got the water and electricity.

The villagers did not.

Officials are excited by so called development.

Dams roads power lines.

They promised better lives.

This was supposed to mean better crops for the farmers

Tens of thousands had to leave the land.

Move out of the way of this dam.

Their lives have not improved.

The government made the promise of electricity for everyone.

Those powerlines lead into the city over the heads of the people.

And in Bangkok there is no difference between night and day.[11]

The story of Tongpan is a classical narrative of development with too many iterations around the world. Of those who pay the price for the progress of others.

Juxtaposed against the seminar room scenes are sequences depicting the hardship of Isaan people. Tongpan has already lost his land during the construction of another dam and now lives with his wife and children in a rented wooden hut without electricity that he is unable to afford. In landscapes already penetrated by over-dimensional power lines and dams, they try to find food in empty waters where once “the fish came to admire the moon and made the water look like silver”[12]. In order to feed his family, Tongpan has taken up many routes; he worked on a US army base, engages in Thai boxing matches, and watches his landlord’s chickens. His salary equals an amount of about 200 dollars per year. Unable to care for his family, his soul and body are visibly shattered. Traumas become parts of our bodies. When it is time for Tongpan to speak in the seminar room he is long gone. His wife has passed from tuberculosis and he is left with children he cannot feed. The student goes looking for him but he is nowhere to be found.

The question of solidarity and participation

Tongpan is a micro-historical zoom into the hardships of one family as a stand-in for so many others. It also performatively unveils the inherent doom of a project of inclusion that was designed to fail, like so many other well intended projects of democracy, of giving people a voice and a place to sit at the table.

But the people do not want to sit at this table. What the people want are other things:

Thank you for wanting to hear a villager’s opinion.

I have not understood everything that has been said.

Water or land.

We want both.

Food and pig and poultry.

These are all things we want.

Other problems were not even mentioned.

The buffalo thieves threaten us with guns.

The rice price is bad.

The officials ask us for rice and chicken.

When we want teak for a house we get arrested.

The big sawmills can take it freely.

They are not arrested.

When we are sick there are no doctors.

We do not even know what they look like.

We cannot buy medicine.

I ask you, will this dam solve these problems?[13]

What the people want is a better life.

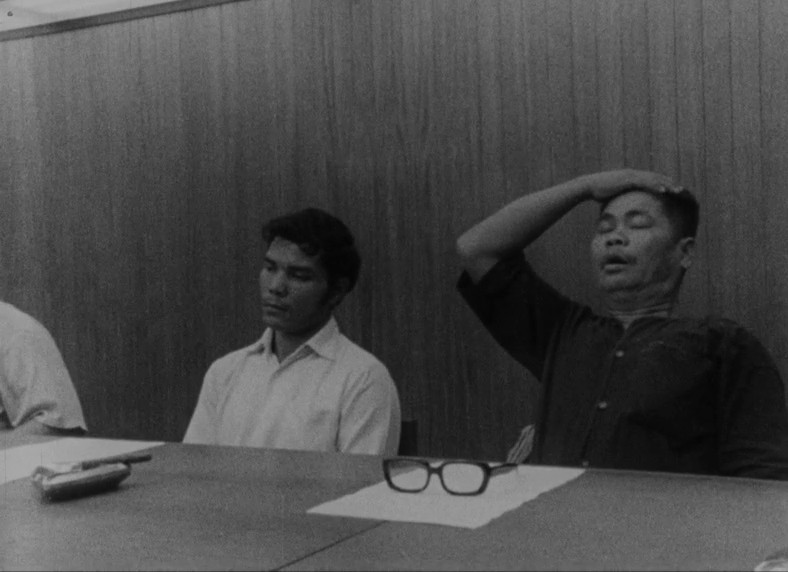

Reading this film and the space of the seminar room as a meta-perspectival meditation on the possibility of solidarity both on and beyond the screen, there are a number of things to be said. More often than not, participation fails to deliver its promises. The farmers in the room are invited as mere performative presences, they are asked to speak only last, when some of them have already left. They do not understand the English words coming out of the White Man’s mouth as he preaches about the benefits of modernity. They feel visibly uncomfortable in this room.

There is a need to move away from the table both methodologically and physically. To move beyond mere tokenism, one needs to understand that colonisation runs deep and includes the hierarchization of knowledge upon which world-making decisions are made. The body of legitimized scientific knowledge inhabited by contemporary neoliberal rationalities needs to be rendered vulnerable. One needs to truly acknowledge the fact that the domains of knowledge of many people are elsewhere. Their wisdom expands what a diagram and number driven decision-making apparatus could ever hold space for. What about dreams and desires? What about all the lore? What about all those epistemologies of the South that are illegible to Western standardized systems of seeing and making the world?

Isaan: The Other Within

The film Tongpan appears in the syllabus of Thai scholar Thongchai Winichakul, who discussed it with his students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in a class on the question of Edward Said’s “Orientalism” in Thailand entitled “The Others Within” as a film “about the Lao people in Thailand”. The region in Thailand’s Northeast is today officially part of the geographical boundaries of the Thai Nation state but most people living there are of Lao or other ethnicities and have more affinities with people on the other side of the Mekong river. Isaan is a region in Thailand that most tourists do not enter. Isaan makes up a third of Thailand when it comes to land and population. Historically, what is now called Isaan used to be a tribute region, only loosely connected to the centre within the mandala system. The region became part of the Thai nation state when Siam became Thailand and all the ethnicities living on the soil of this vast geographical area were bundled up into the new nation project of centralised modern-nation-making in order to be legible to Western standards of social organisation, and to not be colonised under the pretext of “‘underdevelopment”’. The name “Isaan” was given to the region by the centre. It roots back to a Sanskrit term and signifies a hierarchical dependency with the centre. Critical voices from within the region reject this imposed name.

Becoming Thai meant unbecoming everything else that one was or could be. Local specifics that did not feed into the modernising agenda were labeled as “backward” and “underdeveloped”, and these constructed stereotypes are still being repeated today. Standard jargon on Isaan revolves around deficient terms like overpopulated, vulnerable to radicalism and in need of development. Notoriously identified with underdevelopment, the region is not arid but it is the driest and poorest region in Thailand. For reasons man-made (dam projects and political power games) and terroir-related (the soil has high saline and salt rock deposits, and the region relies heavily on seasonal rainfall) the landscape is barren and getting a grasp on the good life is harder than elsewhere.

Rather than addressing larger causes of social injustices, poverty is often framed as having a natural cause in the arid land. But this planet has seen places that are much drier and still have accumulated unfathomable wealth. It is also not right that nothing is growing in the region. It is just that the agricultural products have been channeled into export trading situations with the profits appropriated elsewhere and only marginal improvements in the areas where these things are produced. Life does get better, just not in the region.

The argument that Isaan is lacking leaks. Yet it echoes and creates realities. The diagnosis of Isaan being in lack of resources, of water, of development acts as meta-justifications. A simplistic causal relation between poverty and communism as well as red shirt political opposition was discursively planted to justify interventions and domination. Dam building projects, like the one discussed in the film, were never only about climate control but also about social control. In 1946 the United Nations Economic Commission for Asia was established, a supra-governmental body to promote economic development as a measure against the spread of communism after Mao’s takeover of China in 1949. Thailand was a close ally to the US, with military bases in the Northeastern part of the country and rest and recreation spaces at the coasts. The country received substantial funding from the US and the World Bank.

The Pa Mong Dam mega-project, to be constructed 20 km upstream of Vientiane, was a proxy for developmental dreams gone wild. The biggest hydroelectric project in the world was to be completed in the 1980s and would fundamentally alter the flow of the Mekong. The Mekong is one of the world’s longest rivers flowing from the sacred geographies of the Himalayan Mountains of Tibet, across the boundaries of China, Burma, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Southern Vietnam into the South China Sea. The idea of “taming” its majestic power was rooted in an extractive idealism of “man over nature” that renders thinkable such mega projects. It is the necessary worldview to believe in capitalism. Rationalized and justified within the parameters of scientific knowledge, its wild beauty was to be engineered and mastered. A project, more in the service of engineer egos than rooted in local lifeworld’s that were scientifically abstracted and reduced to data sets: 98 m high, a storage capacity of over 100 billion cubic meters, up to 4000 MW, irrigation of 2 million hectares at the cost of 1 billion USD. All this with an estimate of 400 thousand people being displaced, species extinct and ancestral energies forever rerouted.

This dam was never built. Lao guerrillas in the region made the dam project a costly risk, and when the Khmer Rouge acceded to power US spendings in Southeast Asia were withdrawn. But many others have been and are still being built.

The quest for a better life is ongoing

Many years into the new and modernised nation the promise of a better life did still not materialise for many. Isaan has become unliveable for many. It is the place where most of the migrant workers both domestic and international come from. Life does become better, mostly because of the transnational money earned by migrant labourers, male and female, that flow into the region’s households and temples. Only 5.8 % of state expenditures go to Isaan, even though about a third of the Thai population lives there.

Ong-art Ponethon, who played Tongpan, got a second role in Sons of the Northeast (1982), another important film in Thai history that deals with the same region. When he won the best male acting award at the Thailand National Film Association Awards, he had already moved to Libya as a labour migrant. The Thai Film Archive looked for him and invited him for a 2013 retrospective. They found him through Facebook. Ong-art Ponethon was not the only one who was lured by labour brokers to work in the construction industries of the Middle East, as the invisible and underpaid workers of some of the world’s most prestigious architectural projects.

Many Thai women who have travelled elsewhere on pathways of marriage migration are also from Isaan. Their marriages are often enabled by marriage brokers operating in bureaucratic grey zones on the borderlines of human trafficking. In the 1990s, printed paper catalogues circulated that marketed the docile beauty and submissive smiles of “The Thai Woman” as a product, available for German men to choose from. The stereotype became operational and created realities.

Since the 1980s, every year between the months of July and September thousands of Thai berry pickers from Isaan embark for Sweden and Finland to pick wild berries in the vast forests of Scandinavia. Based on a customary right that allows everyone to pick wild fruits, this has now become part of a globalised commodity chain involving labour brokers, factory owners arrested for human rights violations and concerned politicians who struggle to frame “modern slavery” within the proud Nordic tradition. In order to get a working permit, Isaan farmers have to take on huge debts and in climatically difficult seasons not all of the workers are able to make a profit at all. Despite bad working conditions as well as repeated violations of human rights many have been embarking on this journey every year It is still the better option towards a better life.

Tongpan touches upon many of the foundational injustices that have historically marked the region and continue to shape life paths in Isaan. Past, presents and futures are folded together in the emergence of migrant lives. It is imperative to understand pathways of migration not merely as individual choices or desires, but to look deeply into those supra-national entanglements – past, present and future – that make migration a necessary, thinkable and desirable option.

Khong Chi Mun: Speculative future making

Framing Isaan subjectivities as the underdeveloped victims of natural, state hegemonic and US imperial powers remains a one-sided story, neither hopeful nor helpful. Looking beside and beyond those meta-stereotypical narratives it becomes obvious that speculative future proposals are already emerging from within the region. And this is nothing new. The history of resistance within Isaan is old, it has just not made its entryways into official history-making.

The Phi Boon Holy man rebellion and uprisings of the early 1900 were an indigenous response to the centralizing and colonising efforts of the Siamese nation state. The Holy Man rebellion was a transnational movement uniting a region over the meta-concerns of colonisation from elsewhere. In Laos it was the French and in Thailand’s Northeast the central government. It was an animist rebellion promising to release the villagers from their suffering. The promise was a better life. The Holy Man uprising was brutally shut down in Thailand and cost the life of many villagers. The leader Ong Keo went into hiding in the Lao mountains and was later assassinated by the French during peace negotiations. Someone smuggled a pistol under his hat, fully knowing that according to Lao customs this hiding spot would remain unchecked.

The Phi Boon Holy man movement spread and found resonance through ballads. The space of the musical was a vessel for critiques and to articulate hardships. This form of rebellion in song also appears in Tongpan. In one scene, outside on a field, we see two farmers, one playing a drum with a bird on his shoulder and the other playing the khene, a Lao mouth organ. They sing about the barren land and “daughters and wives taken away for others’ pleasure”[14]. This scene is an antidotal entry-point to the scientific rationality of the seminar room. A space to become attuned to other, de-colonial, Southern epistemologies. During the short period of formal democracy when the film was made Pleang Pheua Chiwit, a form of Thai folk rock inspired by Western protest music and working-class solidarity, was emerging.

The question of a better life for the people in the region and whether this would have been fulfilled by the Holy Man will never be answered as this version of history was not actualised. In order to not naively romanticise from a distance, it is also important to consider that the pre-state was not a paradise but was very violent to some. There are stories in which the hill tribes were not mere innocent victims sucked into state power but were themselves engaged in slave trading operations, over which they wanted power back. A less noble reason for rebellion than relieving the villagers from suffering. There were also prophecies persuading the villagers to abandon their harvest and collect pebbles that would turn into gold.

In official discourse Thailand still prides itself in having never been colonized. There is inclusive racism in the ideal of Thainess and there is colonialism that differs slightly from its standard definition: proxy-colonialism. The global vocabulary does not accommodate these peculiar and specific circumstances and it remains difficult to talk about those things, resistances articulate themselves elsewhere. Up until today all those unfulfilled dreams and desires of a better life on one’s own terms, a life of dignity, still linger and form into rebellions against centralized rule. The ongoing violence in the Deep South of Thailand is only one other example of these reverberations and unresolved questions.

What remains are potentialities. Other ways that things could have gone down. Within the region, there are attempts to revisit this part of history, with merit making ceremonies and the creation of a museum.

In contemporary Northeastern Thailand, a quest towards other futures materializes in the collective proposal for a new name brought forward by a group of activists, scholars and progressive artists. It refers to the three rivers adjacent and parallel to the Mekong river, the Khong, Chi and Mun. Isaan becomes Khong Chi Mun. A chosen name that does not refer to the centre but relates to terroir.

Thank you to Sarnt Utamachote, my co-curator at the un.thai.tled Film Festival for introducing Tongpan to me, to Kong Rithdee & Putthapong Cheamrattonyu from Thai Film Archive for the insightful conversation and helping with film stills and Paijong Laisakul for granting me the rights to use film stills. This writing is also inspired by my conversations with Thanom Chapakdee on the internal colonization of Isaan.

Endnotes:

- Itinerant outdoor screenings with fluid spectatorship in villages predated official movie theaters with concrete walls in many parts of the world. During the Cold War, these spaces were hijacked by USIA (United States Information Agency) sponsored screenings of anti-communist and pro-development films as part of US development policy, where ‘educational’ documentaries were spread into ‘underdeveloped’ areas (such as Indonesia) that they called ‘Third World Countries’ (see van Heeren 2012: 60-62; Naficy 2003). In Thailand likewise, the social spaces of the movie screening were used to ‘propagate anti-communist messages and feelings’ (Adadol 2018: 9) and in other localities, like Iran, schoolchildren in villages were also exposed to development propaganda films (Naficy 2003).

- Common Cold Film Festival post-screening discussion with Kong Rithdee & Putthapong Cheamrattonyu from Thai Film Archive, 2021.

- Common Cold Film Festival post-screening discussion with Kong Rithdee & Putthapong Cheamrattonyu from Thai Film Archive, 2021.

- Common Cold Film Festival post-screening discussion with Kong Rithdee & Putthapong Cheamrattonyu from Thai Film Archive, 2021.

- Common Cold Film Festival post-screening discussion with Kong Rithdee & Putthapong Cheamrattonyu from Thai Film Archive, 2021.

- Common Cold Film Festival post-screening discussion with Kong Rithdee & Putthapong Cheamrattonyu from Thai Film Archive, 2021.

- Quote from Tongpan (1977).

- Quote from Tongpan (1977).

- Quote from Tongpan (1977).

- Quote from Tongpan (1977).

- Quote from Tongpan (1977).

- Quote from Tongpan (1977).

- Quote from Tongpan (1977).

- Quote from Tongpan (1977).

References:

Heeren van, Katinka. Contemporary Indonesian Film; Spirits of Reform and Ghosts from the Past. Brill, 2012. https://doi.org/10.26530/OAPEN_420331.

Ingawanij, May Adadol. “Itinerant Cinematic Practices In and Around Thailand during the Cold War.” Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asiano. 2 (2018): 9–41. https://doi.org/10.1353/sen.2018.0001.

Naficy, Hamid. “Theorizing ‘Third World’ Film Spectatorship: The Case of Iran and Iranian Cinema.” In Rethinking Third Cinema, edited by Anthony R. Guneratne and Wimal Dissanaya, 183–201. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. “Epistemologies of the South and the Future.” From the European South, no. 1 (n.d.): 17–29.

———. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide. London New York: Routledge, 2016.

———. The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

Rosalia Namsai Engchuan is an artist and researcher whose practice draws on decolonial, multispecies, and queer theory. She has written widely for art and academic publications on contemporary art and epistemic violence, and lectured internationally at Cornell University, Harvard University, HKB Fine Arts, NYU Tisch School of the Arts, and Sandberg Institute. Her PhD at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology and Friedrich-Alexander University centers on decolonial epistemologies. In collaboration with knowledge holders outside of modern scientific and state health infrastructures, her ongoing intuitive research is invested in the imperatives, promises and desires of decolonial healing practices. Rosalia curates screenings and dialogical encounters with un.thai.tled and the Forest Curriculum and was the 2021 Goethe-Institut fellow at Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin.