Reminiscences of a Journey to Okinawa:

‘Fūkei’ (landscape), as a multilayered discursive concept, or in Karatani Kojin’s terms, ‘an epistemological constellation’ (1993, 22), has intersected with a critique of (Japanese) modernity in cultural and artistic realms. In Karatani’s analysis of Japan’s modern literature since the Meiji period, he points out how the emergence of ‘landscape’ correlated with the formation of the ‘modern self’/subjectivity (1993, 38).

In art historian Yamanashi Toshio’s volume on the emergence and evolution of Japanese landscape painting (fūkeiga), he notes the preference of Japanese ‘yōga’ (Western painting) artists for titling their own works ‘fūkei’ when entering national art exhibitions in late 19th century (2016, 95–96) as a way to clarify their changed/changing perspective (manazashi) concerning nature, where the establishment of ‘landscape painting’ as an autonomous genre is expected. Following W.J.T Mitchell’s proposal that landscape should be grasped ‘as a verb…a process by which social and subjective identities are formed’ (2002, 8), it can be seen how Yamanashi’s exploration is weakened by the absence of a critique of modernity that should have turned not only to how the perception of landscape is contingent upon the development of technology, infrastructure, and bodies of knowledge, but also how fūkeiga indeed constitutes part of the plural projects of modernity, including that of Japan’s imperial formations.1 Manazashi should be problematised in relation to the politics of ‘gaze’, a configuration of power underpinning and complicating the ways of seeing.

Reflecting upon imperialism, Mitchell understands landscape as ‘a physical and multisensory medium… in which cultural meanings and values are encoded’ (2002, 14). For him, a reading of landscape could carry an ethnographical connotation that underscores an encounter ‘in an odd, disturbing, liminal space, the threshold between two cultures’ (27). Such a tendency in theorising landscape as a relational medium through which ‘I’/‘We’ encounter the Other and establish the epistemological understandings about the latter has also underpinned ethnographic filmmaking (see Rony 1996). Significantly, exploring the intersection between Western ethnographical cinema and essay film, Laura Rascaroli coins the neologism ‘ethnolandscape’, using it as a ‘framing device’ to understand ‘landscape as the product of a specific gaze stemming from a number of traditions and discourses that combine art, science, and popular entertainment, spectacle, power, and ideology’ (2017, 72).

Turning to the often-cited examples of fūkei eiga (the Japanese phrase is used here to differentiate this historically specific strand from the general spectrum of ‘landscape film’) in relation to their ideo-theoretical articulations of fūkeiron (theory of landscape), we may say the framing of ethnolandscape could hardly contain fūkei eiga. Fūkeiron critics started to make fūkei eiga at a time when the New Left student movement showed signs of fragmentation and stagnation amidst Japan’s rapid urbanisation and development in the 1960s (see M. Matsuda 2013b). Seeking to politicise and problematise the landscape as part of its critique of governmentality, fūkei eiga interrogated the ‘nonspectacular and nonrepressive mechanisms of control and governance built into the everyday environment’ (Furuhata 2013, 118). This can be explored through closer examination of two fūkei eiga works: A.K.A. Serial Killer (Ryakushō renzoku shasatsuma, 1969), directed by Adachi Masao in collaboration with a crew of intellectual-filmmakers including Matsuda Masao, and a segment in Oshima Nagisa’s fiction feature, The Man who Left his Will on Film (Tokyo sensō sengo miwa, 1970). [2]

While critiquing an urbanising, homogenising ‘Japan’, fūkeiron does not foreground ethnocultural differences and the problematic of gaze—such dissatisfactions have allowed little room to interrogate how the drastic transformations of the landscape also related to the multifarious biopolitical projects in (re-)configuring the ‘Japanese nation’ (infrastructure and population) in the late 60s and early 70s, which is crucial to the discussions surrounding Okinawa.3 Hence it is necessary to open up the ‘theory of landscape’ and consider it an assemblage of heterogenous conceptualisations interlacing with multiple projects of landscape filmmaking (image-making) so that other differentiated articulations from the cinema/art world could be addressed (see Hirasawa 2010).4 To approach fūkei eiga from the perspective of essayistic filmmaking, we may further question how the modernist and transgressive essayistic form of fūkei eiga—commensurate with the fūkeiron thesis yet by no means constrained by it—registers no less critical potentiality.

Opening-Up the Interstices

In recent years, the study of the essay film has recalibrated interest in challenging its Eurocentrism in theory production and geopolitical hierarchy (Hollweg and Kristić 2019; K. T. Yu and Lebow 2020). At the same time, it has expanded from a (post)structuralist mode that asks ‘what essay is’ to interrogating what the essay does—particularly, how essay film thinks (Rascaroli 2017; Warner 2018). As indicated by Yu, a translocal and transnational perspective on essayistic cinema is required to pay more attention to the ‘alternative methods of interrogation’, particularly to the ‘features of the essayistic and the “screen-writing” process in cultures with different socio-political contexts, distinctive cultural, philosophical and literary traditions, as well as unrelated linguistic structures’ (2019, 173). The aesthetic and epistemological potentialities of the essay film should not be reduced to a checklist of generic characteristics and filmmaking approaches that have presumably ‘spread’ or been ‘translated’ from its Euro-American centres to non-Western locales, for example to the 1960s Japan (see Rascaroli 2017, 3).

Importantly, the ‘essayistic’ can be used strategically to foreground ‘the transgeneric character of the essay, its propensity not to stay put within a single set of attributes’ (Warner 2018, 6). Addressing the politics of the essay film, Rascaroli has emphasised its ‘anachronism’ (Rascaroli 2017, 5–6). For her, a ‘future philosophy’ underlies the transgressive nature of the essayistic form, regarding how it is ‘inherently contrarian, not of its time, and incessantly transforming’ (2017, 188). In unpacking essayistic thinking, Rascaroli uses Gilles Deleuze’s conceptualisation of ‘interstice’ to examine the ‘filmic in-betweenness’, the location of ‘epistemological strategies’ mobilised by the essay film to facilitate its ‘thinking’ (2017, 7;15).

Deleuze designates interstice as ‘the method of BETWEEN’ and ‘the method of AND’ (1989, 180), locating interstice ‘“between two images”…Between two actions, between two affections, between two perceptions, between two visual images, between two sound images, between the sound and the visual’ (1989, 180). For Deleuze, interstice is specific to the discussion of time-image: whereas in movement-images, the flow and association of images or sequences can be grasped by the ‘sensory-motor linkage’, made perceptible often through the actions of the film protagonist(s) who would navigate the audiences through the diegetic space upon a narrative logic of linearity. In the regime of the time-image, however, the ‘sensory-motor linkage’ is loosened and breaks down, wherein ‘perceptions and actions cease to be linked together’ (1989, 40-41). Interstice then underpins how a series of images and soundtracks are configured and connected via the ‘disjunction’, understood as ‘an incommensurable or “irrational” relation which connects them to each other, without forming a whole’ (Deleuze 1989, 256).

Agreeing with Rascaroli that the interstitial aesthetics is not only specific to essay film, we may take interstice as a critical heuristic to approach the formal disjunctures and stylistic incommensurables concerning the landscape films under examination. Turning to how the progression of the series of images (and soundtracks) is opened up to uncertainties and probabilities, we could focus on essay film’s spectatorial engagement. For Timothy Corrigan, what the interstice creates is not ‘spectatorial “identification”’, nor ‘a version of Brechtian “alienation”, a position of unfamiliar exclusion from that world represented’, but ‘a suspended position of intellectual opportunity and potential’ (2011, 44). Generative of an association of potentiality and new meanings that radically call images into question, interstice is therefore closely associated with a ‘thinking spectator’ (Rascaroli 2017, 10).

Meanwhile, although interstice still allows us to attend to the issues of (authorial) subjectivity and reflexivity that underline the essayistic form, the analysis is not necessarily confined to the enunciation (of the self) and vococentrism, namely ‘the cinematic soundtrack’s prioritisation of the human voice over sound effects and music’ (Harvey 2012, 7). Considering the attention paid by David Oscar Harvey to the ‘modes of perception and affect’ in non-vococentric essay, one could use interstice as a useful angle to unpack how certain landscape films engage spectators via ‘the compositions of the image, editing or non-vocal manipulations of the soundtrack’ and so forth, even in cases where the voice-overs are not deployed to directly articulate personal reflections, or when the films ‘inquire, opine, wonder, and doubt, but without words’ (2012, 20), which is instrumental in grasping Takamine Gō’s Okinawan Dream Show. In A.K.A. Serial Killer, for instance, while the ubiquitous point-of-view shots in hand-held style suggest the strongly-felt presence of the author(s), arguably, the authorial ‘voice’ mainly emerges ‘from the play and arrangement of images’ in relation to the interstitial strategies (Harvey 2012, 19). For Adachi and his comrades, their daring ‘re-enactment’ is an experiment in the possibilities engendered through a journey of virtuality, wherein the images (soundtracks) are assembled in a non-hierarchical, anachronistic manner wherein each shot or sequence is rendered autonomous and becomes independent from the shot preceding or following it. Onto such a ‘space of virtual conjunction’ (Deleuze 1997, 109), the viewer is provoked to imagine places that Nagayama could have visited (or attempted to go, such as Hong Kong), and to envision the landscapes that the young man could have seen and experienced (see Adachi and Hirasawa 2003, 287–300).

Okinawa: The Contested Landscape

The Okinawan landscape under the Government of the Ryukyu Islands (GRI, 1952-1972) and USCAR5 can be grasped in relation to a multiplex of discursive and biopolitical projects manufactured, choreographed, reproduced, and distributed by heterogeneous inter-related institutional and individual actors and components working through and across various geopolitical locales/scales. In his 2003 article about the cinematic gazes towards Okinawa (and its landscape) in Japanese cinema (mostly fiction films, including Takamine’s), Aaron Gerow suggested that the filmic representation of Okinawa is in itself ‘a site of struggle between conflicting forces’ (2003, 275)6 .We may take (Okinawan) landscape as the medium (and mechanism) through which the above-mentioned interrelations and frictions—which are ‘constantly made and unmade within the ever-shifting flow of power and affect they themselves constitute’ (Inoue 2019, 155)—are made seen, heard, sensed, and interrogated.

For instance, historian Gerald Figal has indicated how the imaginary of ‘Tourist Okinawa’ had been planned and manufactured infrastructurally and discursively, both before and after the 1972 handover, as a result of the governmentality of entangled negotiations between the US, the Japanese government, and the local Okinawan policy-makers. For Figal, to grasp what had characterised Okinawa’s pre- and post-Reversion transformations, it is necessary to contextualise two strands of competing popular images of Okinawa’s landscapes: the ‘battlefield’ consisting of war ruins, memorials, monuments, and so forth (associated with the ‘memorial boom’ in the mid-1960s), and the ‘tropical haven’, often associated with the islands’ natural resources, and accentuated with the exotic ‘south island feel’ (nangoku tekina kibun) (2012, 53;92). An image politics as such has been further complicated by the US occupation (1945-1972) and specifically, the continued US military presence across the islands since the Reversion (Figal 2012). Importantly, ‘Tourist Okinawa’ highlights a representational trope that unfolds along a teleological plane wherein Okinawa/Okinawan landscape is flattened into ‘the prediscursive bedrock upon which the foreign forces of modernization and militarization are laid’ (Inoue 2019, 155) –it gives little room to envision the ‘coevalness’, the ‘contemporality between the subjects and objects in an inquiry’ (Chow 2010, 120), or to foreground the contingency and complexity underlying the interrelations between the ‘cognitive categories such as nation and race around the figurations of “Japan”, “Okinawa”, and “the United States”’ (Inoue 2018, 537). 7

Takamine Gō’s Affective Landscape

While a student of fine arts, Takamine Gō started to film Kyoto with an 8-mm camera, which he would call ‘the maternal-body of (my) self-expression’ (1992, 128). For Takamine, neither the politically-engaged model nor the mode of ethnolandscape was preferred given how he saw the risks implicated in the epistemological process of making symbolised and sometimes auto-ethnographical truth claims about Okinawa, its landscapes, as well as Okinawan identity. Rascaroli stresses that the ethnolandscape is productive of ‘an ethnographic subject’—it is ‘pictured as a landscape, which is itself at once framing device and part of the picture, scientific display and exotic spectacle’ (2017, 74). Even though Takamine did not straightforwardly deal with such self-awareness of othering wherein Okinawa/Okinawan people may constitute part of the ‘picture’, ‘display’, and ‘spectacle’, it was due to the very reluctance in positioning himself as an epistemic, knowing subject within/apropos Kyoto’s ethnolandscape that Takamine started to grapple with his identity crisis, which was also exacerbated by Okinawa’s imminent Reversion. For him, Kyoto, the picturesque ancient capital ‘had always been part of Japan’ (2003, 28): ‘the light odor of the air, the cherry blossom, the mist, the canal, Kamo River, Kyoto dialect, people’s faces. I think the “core” (shin) of the landscape here differed from that of Okinawa’s’ (2003, 24). Admittedly, Takamine found Kyoto’s landscapes ‘very exotic’ (ikokujōcho ippai) (Nakazato and Takamine 2003). Meanwhile, for him, the landscape is always already a representation, and thus it could be and needs to be grasped through/in the (cinematic) images of the pro-filmic space. Takamine stressed that he turned his camera to Okinawa’s landscape not necessarily because he was driven by his ‘(political) awakening to the Okinawa problem’–mainly referring to the issue of US military bases, but mainly because he considered filmmaking a way to fulfil his ‘personal desire for expression’ (jibun no hyōgenyoku) (Nakazato and Takamine 2003), that is, landscape, or to be more exact, landscape film(making), constituted a medium through which he could explore and rearticulate his subjectivity.

When emphasising Dream Show as the ‘original point’ for his film oeuvre, Takamine elucidated,

The question of the Okinawan landscape (Okinawa no fūkei) does not concern political issues such as to represent Okinawa, but the landscape as it is (arinomama no fūkei sonomono, emphasis mine). The landscape does not carry a core of its own, and there is no hierarchy attached, so there is no centre (in landscape) either. What constitutes the axis is my personal perspective. Leveraging this personal instead of a generalising perspective, I could take a grip on the non-differentiational/equal value (tōka-sei) of the landscape.

…there is the base, the blue sea and the market (a landscape that could be easily symbolised). They are not necessarily my concern. I think I could turn the everyday and chirudai into films. If the everyday time cannot be tapped into, we cannot reach the real landscape (quoted in Takamine 1992).

It is intriguing that Takamine also emphasises, ‘so far as I’m watching the landscape, it’s not that I’m an onlooker (bōkansha) per se. I think I was using my 8-mm camera to sniff the stench of death (fūkei no shishū) in the landscape’ (Nakazato and Takamine 2003). ‘Fūkei no shishū’ is a key term used by Matsuda Masao to connote the grave outcomes of the student movements. Takamine nevertheless revamped this term to evoke an affective understanding apropos the actual aftermath and traumatic memories about the Battle of Okinawa8—despite the existence of war memorials around the islands, he suggested, the ‘mabui’ or the soul of the deceased, while remaining part of the Okinawan landscape, was never well ‘sorted out’ (also see Nakazato 2007). Hence, the filmmaker suggested, ‘…my camera is like a vacuum cleaner (sōjiki) that sniffs the smell (of the landscape)’ (Nakazato and Takamine 2003). Accordingly, such an awareness is directly related to how Takamine would film the landscape in Okinawan Dream Show: to capture the ‘smell’, he would privilege long takes and shoot in a one-cut-one-scene style, without panning or zooming (Takamine 1997, 28). He also determined that, for instance, ‘We do not play filmmaking to pretend ours is a Ryūkūan film and simply leave the burdens in Okinawa’s hands’ (1997, 28), ‘we shall give up the self and try not to ride on the tides of the Reversion Movement, in not filming or not being made to film the landscape that will symbolise the Movement’; ‘simply because it is our families, friends and acquaintances, or it’s the mundane landscape, then they will not be featured in our film—we don’t make such decisions’ (2003, 29).

Takamine underscored his landscape filming as a subjective, multisensory act that goes beyond the codified representations of the profilmic real. In stressing the significance of mabui, he was turning to what remained invisible and inaudible in the landscape. Moreover, chirudai, originally an uchinā-guchi term used to describe a kind of dreamy state of physical fatigue and powerlessness due to disappointment and loss, frames a discursive articulation and a filming approach for Takamine to negotiate his subjective positioning both as an essayist and an Okinawan. The filmmaker himself reinforced that chirudai could be roughly translated as ‘sacred lethargy’, with its ‘sacredness’ deriving from Okinawa (Ryūkyū)’s interconnections with the natural-ecosystem of the ‘universe’ that could not be assimilated into the ‘Yamato’s ways of life’ (1992, 129). In Okinawan Dream Show, Takamine leveraged formal experimentations to configure the ‘in-betweenness’ of chirudai, here understood as a specific assemblage of temporality and affect.

One may better understand chirudai and its connections with the so-called ‘tōga-sei’ of the landscape if one takes a closer look at Okinawan Dream Show. Riding on the 750cc Honda motorcycle of his friend Tarugani (who was also the sound-recordist), Takamine filmed around places like Naha, Itoman, Koza, and Takamine’s birth village of Kabira at Ishigaki Island. He spent almost four years developing this project (Takamine 2003, 28-29). A road movie of sorts, the film consists of eight segments, each organised around a different shooting location (unrecognizable in the film but indicated on the DVD menus), such as Kokusaidōri (the main avenue at Naha), along the Ichigōsen (National Route 58), and finally Ishigaki—these are collections of wanderers/flaneurs who see rather than act: sometimes they knowingly appear in front of the camera. For example, groups of curious children; a kind-looking woman holding hand with a child, with another at her back (3); a young couple waiting for a bus to come; the black American soldier at Koza who talks to the camera through muted images. For the most part, they are observed at a distance, such as the distraught-looking man pacing back and forth outside of the Employment Security Bureau (see Takamine 1997, 28), or the gangs of Koza’s high-schoolers. Yet the sequences, mostly shot with a fixed camera, are tableau shots observing the quotidian urban environments and everyday scenarios without using diegetic sound or narrative devices (e.g., voice-over, intertitles)—although by no means silent. Despite the occasional appearance of vernacular architecture (such as the turtle-back tomb) and street views (with palm trees; national flags of the US and Japan), or random sights of Western tourists and mixed-race children, who were walking side by side with local ladies in kimono and salaryman in suits, hardly any iconic images signifying the ‘Tourist Okinawa’ stand out.

Crucially, shot at a speed of 36/54 frames/per second and played at the normal pace of 24/fps, all the movement and actions in Okinawan Dream Show attain a disparate rhythm and seem to unfold in slow motion. Despite the absence of voice-over, the soundtrack was a labyrinthine experimental mixture of folk shima-uta songs, ambient sound recorded along filmmaking trips (e.g. daily conversations), and radio programs (sometimes out of sync), wherein both Japanese language and uchinā-guchi interweave and sometimes become indistinguishable (see J. Matsuda 2019). Devoid of any narrative tension, this film configures a landscape (and soundscape) of chirudai or an autonomous temporal-affective sphere of liminality that is not divided or confined by the period-defining Reversion: here sequences shot before and after the Reversion are mingled, and each sequence constitutes an interval capturing an encounter with passers-by and flaneurs whose backgrounds and personal histories are not revealed intelligibly even though among them there are the filmmaker’s families and friends, a point I shall return to. Onto the interstitial space of chirudai, the images (and sound) do not correlate with each other hierarchically or are assigned importance for diegetic, symbolic signification, underscoring Takamine’s earlier reference to ‘tōga-sei’, or equal value.

My Own Private Okinawa

While working on his landscape project, in 1974 Takamine came across Jonas Mekas’ Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania, a diary film tracing Mekas’ return to Lithuania to meet his mother and families after 27 years of exile in the US. Mekas’ poetic documentation about his homecoming journey proved extremely inspiring, which prompted Takamine’s return to his own birthplace of Kabira for the first time since he left as a child (see Takamine 2020, 60–61) (Figure 4).9 However, it was less the diary form per se than the very freedom promised by the formal and affective potentialities of essay for personal expression that Takamine found illuminating. Deeply touched by Mekas’ vision, Takamine came to realise that his ongoing 8-mm project could also be labelled as ‘cinema’(eiga) after all, even though he was not professionally trained as a filmmaker. He suggested, ‘if there can be something like a “Mekas’ film”, even if it sounds a bit improper, I thought it should be OK if there is a “Takamine’s film”. Even if you are returning to your native place and touch the pillar of the old home you were born, that could also become (the subject of) a film’ (2003, 32).

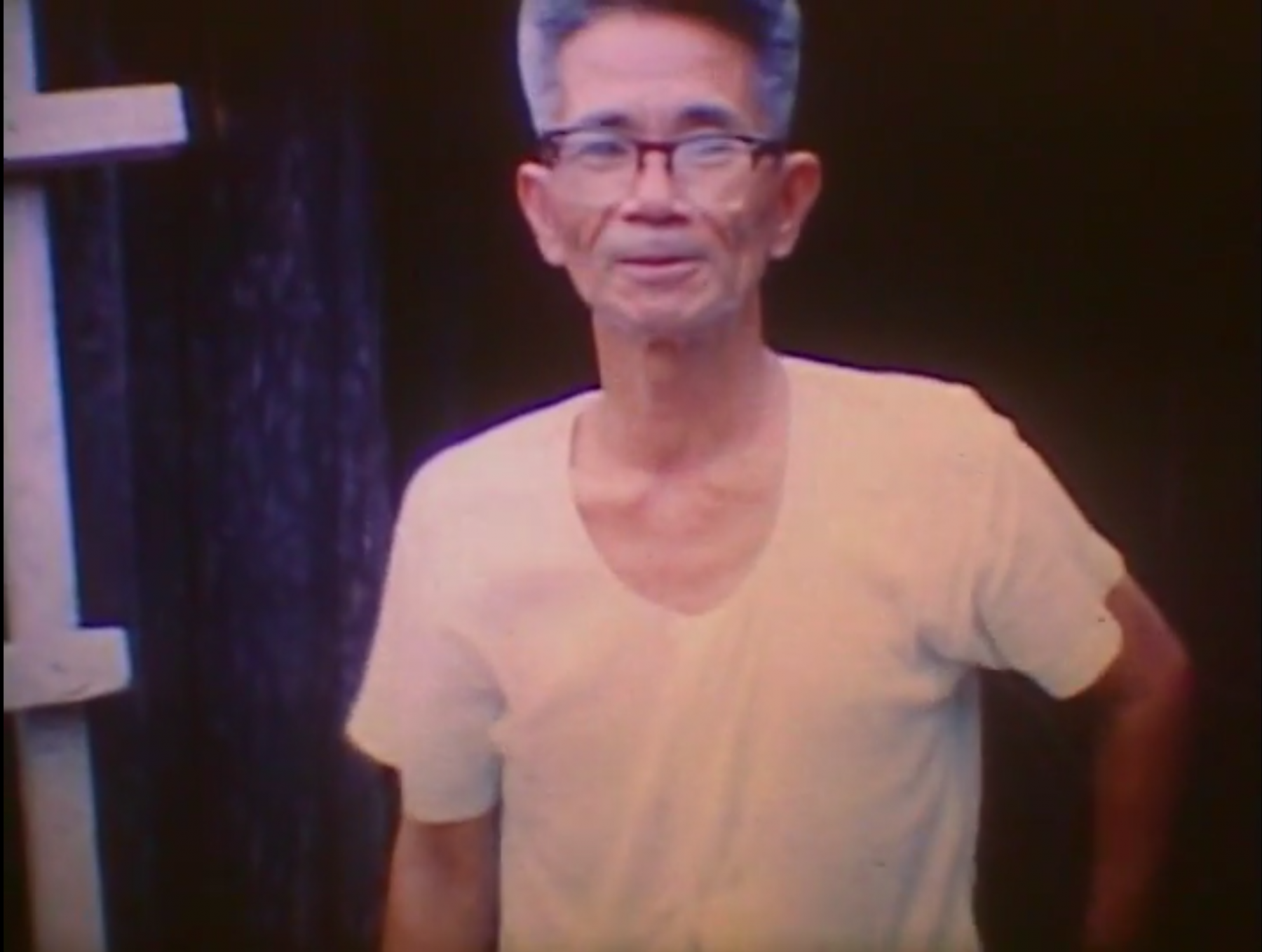

The authorial subjectivity in Okinawan Dream Show is reinforced by its autobiographical, personal dimension, which is also integral to grasping Takamine’s landscape film. Toward the end of the film, Takamine returns to Kabira. In observational style, with his hand-held camera, the filmmaker looks around what seems to be a family-run workshop where glass bottles are packaged, followed by a sequence of a boisterous family gathering wherein the camera patiently examines the faces at the banquet and mundane objects in the room. In the segments to follow, the audiences repeatedly see a thin man in focus, wearing a white short-sleeve shirt and glasses, who would gaze at the camera and smile—Takamine’s father, a detail confirmed by a brief glimpse at the shop name written on a minivan nearby, ‘Takamine Sake Brewery’ (Takamine Shuzōsho) (Figure 5).

How may Okinawan Dream Show help us to recalibrate our understanding of landscape film in Japan and beyond, as well as essay film in general? Theorised under the premises of logocentrism and vococentrism, a first-person essay necessarily registers the authorial self-representation apropos her/his familiar or familial relationship through the author’s on-screen presence, or via the voice-over narration by a strong enunciator. As a non-vococentric essay, Takamine’s take illustrates the paradoxical conditions that the filmmaker’s ‘self’ is enmeshed within while negotiating the different layers of time and differentiated epistemological regimes: in-between a ‘man with a movie camera’ returning to his hometown and meeting his father and family, and the reminiscences or imaginations about such reunions and homecomings; in-between an Okinawa grasped through the teleology of Reversion and ‘Tourist Okinawa’; and the landscape of virtuality, of chirudai. Even though chirudai is considered pleasant by the filmmaker, it can also be experienced as a sentimental journey wherein Takamine invites his spectators to participate and reflect upon the moment of encounter as a moment lost which could possibly be revived via the manipulation of images, a theme he began to approach in his first experimental short, Sashingwa (1973), that used old photographs from his family album.

For the spectators, what becomes significant is less a concern with what the profilmic events are about and more of a regard for how to make sense of the peculiar distribution of time. Okinawan Dream Show was meant to be an installation of affect: its invented rhythm connects with the spectators’ body, encouraging them to invest in a collaborative work to experience the lapse of time while evoking their own memories, dreams, and imaginations. At the early stage of the film’s independently organised screenings in the 1970s, live performances of folk songs were arranged so the screening in itself would promise to be a public event of sensory mobilisation, wherein audiences complained about its ‘drowsy’ nature (see Takamine 1992, 127; Takamine 1997).10 Okinawan Dream Show challenges us to rethink Okinawa’s socio-historical and cultural circumstances in the time of its production, as well as today.

Also, Takamine’s filmmaking prompts us to ask how we may emplace the landscape films that have been examined so far within larger debates concerning Japanese nonfiction/documentary filmmaking. Reviewing the spectrum of landscape films historically, we need to see how the authorial subjectivity in these works had been reinforced toward an articulation of the self, though it is insufficient to ascribe the turn to the personal only to transgenerational differentiations. For instance, Hara Masato’s The First Emperor (Hatsukuni shirasumeramikoto, 1972) could be considered a first-person travelogue/essay—a critical reflection on Oshima’s The Man who Left his Will on Film, the landscape segments in the essay embodied Hara’s own ‘landscape theory’ (1977). While indicating the personal turn, Okinawan Dream Show did not interrogate the self by articulating identity politics and postcolonial, poststructuralist framings that could have further contextualised Okinawan identity and subjectivity. As discussed above, although Takamine’s assemblage of chirudai is not necessarily a critique built upon ethnolandscape and postcolonialism, it is no less political, inspiring us to reflect upon the possibilities of moving beyond the logocentrism and vococentrism underpinning the current existing ‘scholarly and critical work on the essay film’ as called for by Rascaroli (including her own earlier study) (2017, 140–141).

Takamine’s work again draws our attention to the transnational influence of landscape films. Fūkeiron and fūkei eiga have inspired contemporary visual artists/filmmakers in their essayistic experimentations such as Nguyen Trinh Thi’s landscape series (2013), and Eric Baudelaire’s collaborative project with Adachi Masao, The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi, and 27 Years without Images (2011). In the future, one shall look at how landscape films constitute interstitial practices, blurring the boundaries between genres and transversing in-between different socio-political contexts.

Endnotes:

- There is no lack of studies on painting, photography and cinema in relation to Japan’s imperial project and the landscape—for instance, we can turn to the production, exhibition, and circulation of kankō eiga or ‘sightseeing film’ as well as travelogue films apropos the colonial landscapes (see Li 2014).

- A.K.A. Serial Killer was directed by a collective of film-maker Adachi Masao, scriptwriter Sasaki Mamoru, film critic Matsuda Masao, Iwabuchi Susumu, Nonomura Masayuki and Yamazaki Yutaka. The film was not released theatrically after a controversial preview screening (Adachi and Hirasawa 2003, 297–299).

- In the eventful year of 1972, the soon-to-be Japanese prime minister Tanaka Kakuei published his influential bestseller, Plan for Remodeling the Japanese Archipelago (translated into English in 1973). Prior to the publication of this ambitious ‘Tanaka Plan’, Okinawa was ‘returned’ to Japan as one of its prefectures (also one of its most peripheral and least developed) from under the American military rule (1945-1972), on 15 May.

- Matsuda also explained that since the importance of fūkei had been directly raised at some film symposium in 1970, it received lot of ‘journalistic’ attention, and figures like Akasegawa Genpei, Tone Yasunao, and Nakahira Takuma brought the discussions further to fields such as contemporary art, drama, music, and photography (2013, 304).

- The United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands (USMGR) existed between 1945-1950, and was subsequently replaced by the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands or USCAR (1950-1972). Okinawa was returned to Japan on May 15th, 1972.

- For other academic output on Okinawa-related cinema and film historiography, also refer to Sera (2008), Yomota and Ōmine (2008), Kawamura (2016); for television, see Kishi, Sensui & Nakayama (2020). In 2003, Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival curated a section titled ‘Okinawa—Nexus of Borders: Ryukyu Reflections’, a heterogeneous line-up of nonfiction and fiction works that featured a Takamine Gō retrospective: https://www.yidff.jp/2003/cat095/03c095-e.html.

- Probably unsurprisingly, the ‘first actual ethnographic fieldwork in Okinawa’ was carried out in the 1950s as a scientific project funded by the US administration in Okinawa (Roberson 2015, 183). It would be meaningful to cross-examine Japanese-language ethnographical films on Okinawa, and film, television and other media works (co-)produced by USCAR’s propagandist organ, specifically regarding how the latter leveraged ethnographical content about Okinawan landscape and its people to frame and facilitate broader ideological persuasion during its rule (see Nakayama 2016; Kishi, Sensui, and Nakayama 2020).

- Battle of Okinawa, (April 1–June 21, 1945), World War II battle fought between U.S. and Japanese forces on Okinawa, the largest of the Ryukyu Islands. The battle was one of the bloodiest in the Pacific War, claiming the lives of more than 12,000 Americans and 100,000 Japanese, including the commanding generals on both sides. In addition, at least 100,000 civilians were either killed in combat or were ordered to commit suicide by the Japanese military. See <https://www.britannica.com/topic/Battle-of-Okinawa>

- Many Japanese experimental filmmakers have cited/celebrated Mekas as an inspiration (such as film essayist Suzuki Shiroyasu) and the interconnections between Mekas and Takamine deserve further study. When Mekas visited Japan for a second time in 1996, he met Takamine at Okinawa, which inspired Takamine to make Shiteki Satsu Mugen Ryukyu: J•M (Private Images of Ryukyu, J.M.,1996). Their meeting was also made into a TV special, Jonas Mekas Shisaku Kikō (‘Jonas Mekas: The Thinking Traveller’s Journal’, hosted by poet Yoshimasu Gōzō, 1996).

- Takamine used an 8-mm projector at 18/24 fps for his live screenings in the 1970s for the slow motion (email with the author).

Acknowledgements:

This essay has been revised based on the same-titled article published on the Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema in 2021. I would like to thank the editor of Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema (JJKC) Michael Rainer and my co-editor Kosuke Fujiki for the JJKC’s special issues on Okinawan cinema in 2021. I am also grateful for the critical insights offered by Bo Wang and Pan Lu. This article is impossible without Mr. Takamine Gō’s generous contribution.

MA Ran is associate professor at the international program of “Japan-in-Asia” Cultural Studies and Screen Studies (eizogaku), Nagoya University, Japan. Her research interests center around an intersection of inter-Asia studies, transnational film and screen cultures, and film festival studies, and she has published book chapters and journal articles interrogating the relations between film movements, the politics of auteurism, and the institutional contexts of exhibition, circulation, and criticism. Ma is also the author of Independent Filmmaking across Borders in Contemporary Asia (Amsterdam University Press, 2019). Besides research, she has also curated screening events of Asian independent films at Osaka, Beijing, Nagoya, and Tokyo (the 36th Image Forum Festival in 2022).