On ‘On Kino’:

(Translated and edited by Pan Lu)

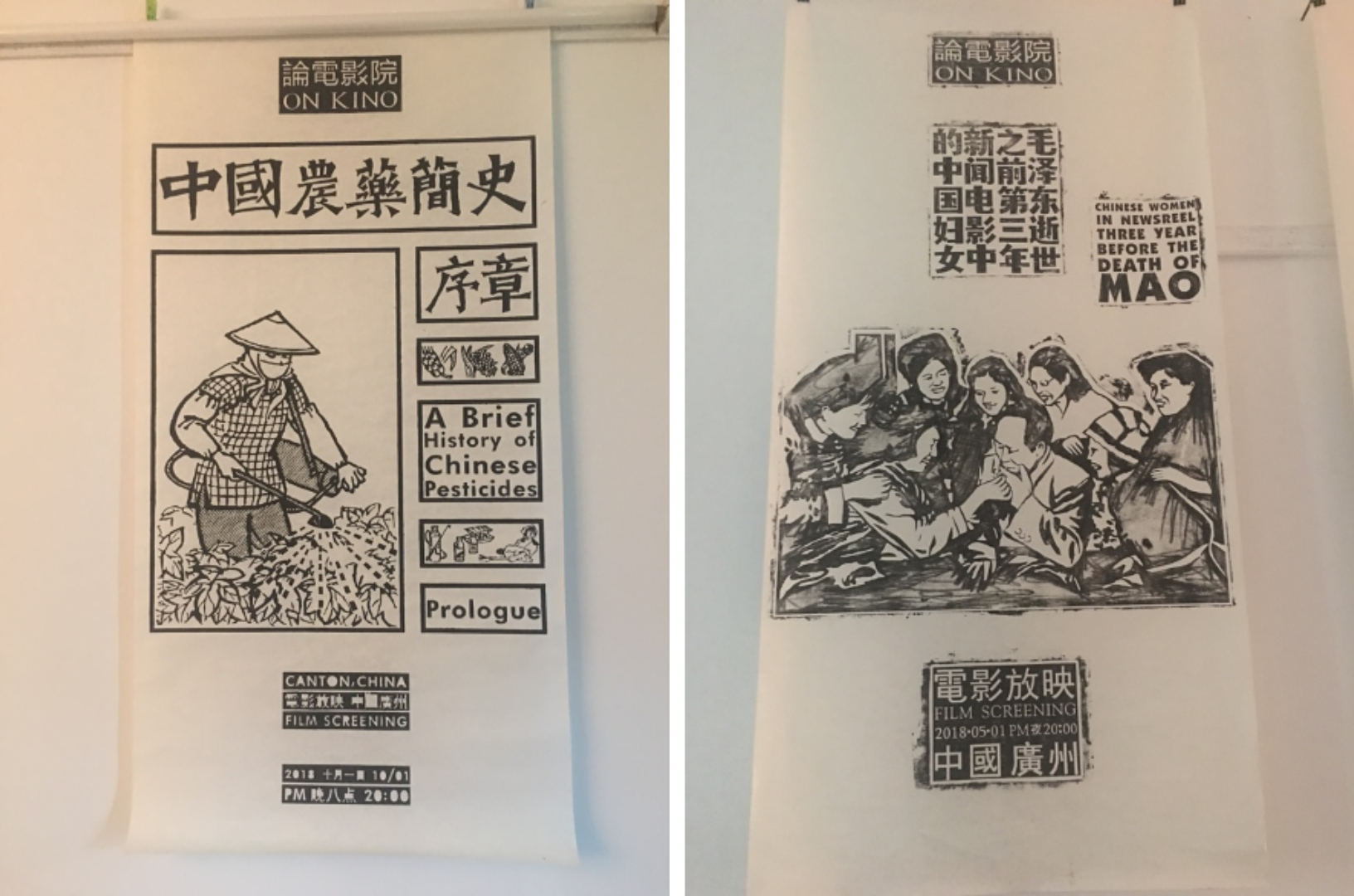

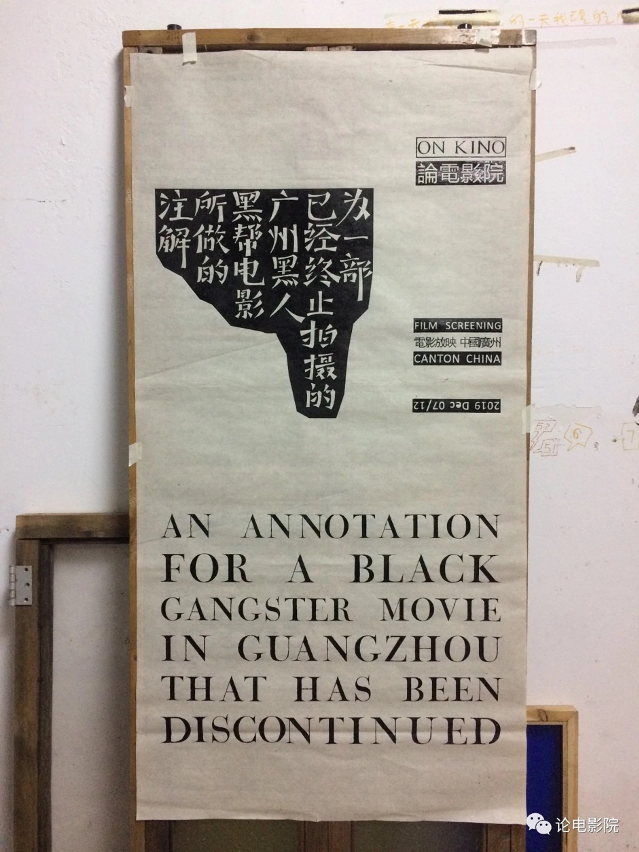

Qin Dao is an artist, filmmaker and publisher based in Guangzhou, China. He is the owner of ‘On Kino’ – a self-claimed film theatre, video screening room and moving image archive all in one in his own living room. Since 2017, ‘On Kino’ has organised regular screening programs that comprise rare, forgotten or orphan films on 16mm, 35mm, 8.75mm, super 8 or VHS formats, most of which have been discovered by Qin Dao himself. ‘On Kino’ also produces woodcut and screen printed posters for movies that might or might not exist. According to Qin Dao, he made a 16mm vampire film in 2016 but could not find any place to screen the film. That was why he founded this film theatre the year after (in 2017). None of us have ever seen this vampire film.

– editors’ notes

1.

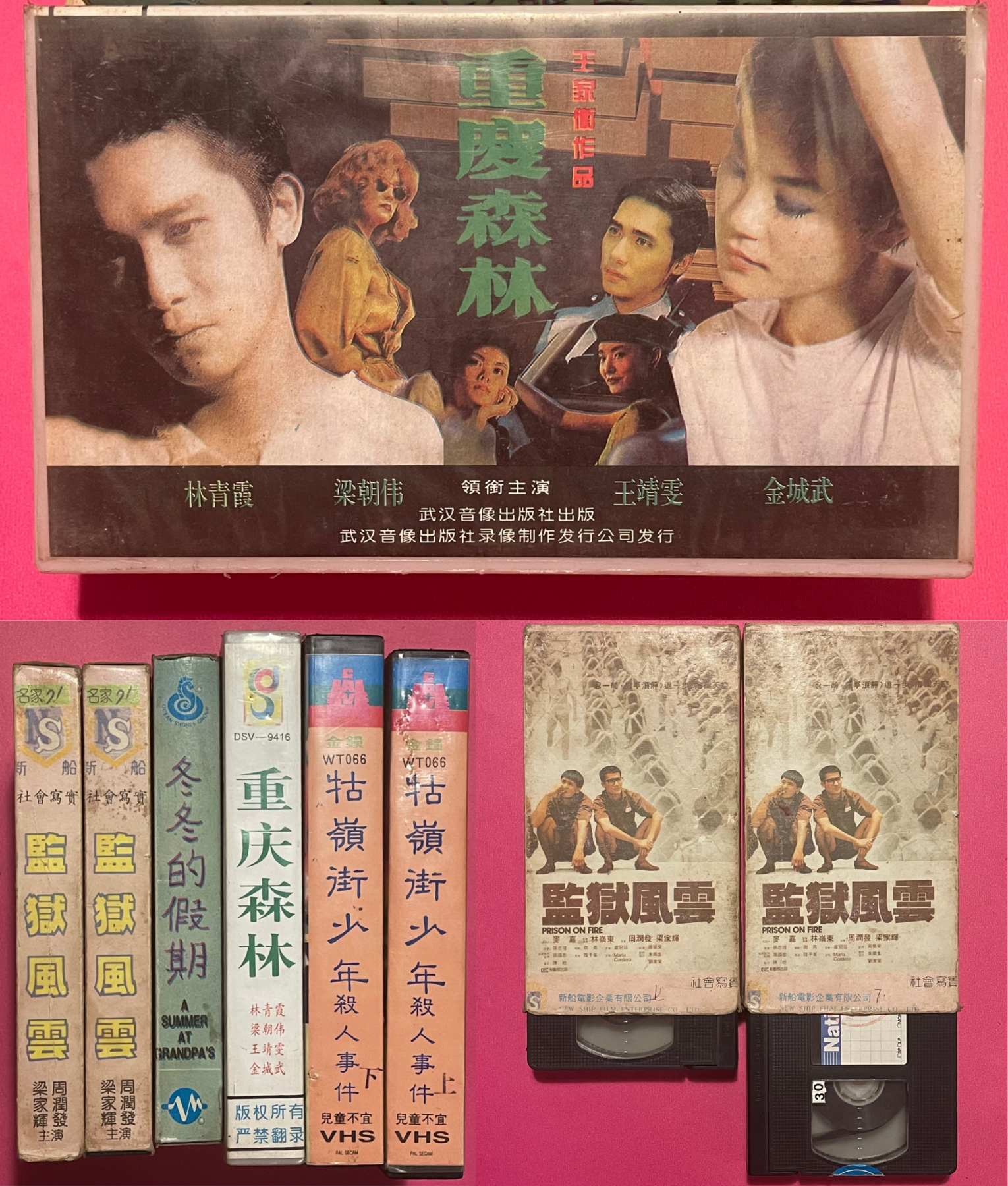

Let’s start the story with something called VCD. In the last two or three years of the 20th century, there was an explosion of film consumption culture in the vast mainland China: it was the culture of VCD (video compact disc), a media format that existed between VHS and DVD. VCD’s short-lived history and the sense of the apocalyptic it carried overlapped perfectly with the arrival of the new century. The widespread distribution of this cheap analogue medium in Hong Kong gave rise to frenzied piracy in the mainland. While the popularity of video disc players meant movies circulated among mainland cinephiles via VCD rather than VHS, there were still many more movies that remained dormant on videotapes, which is now a totally obsolete medium in China and most other places in the world. But videotape films in China have a very interesting history.

Home video tapes were introduced to China in the early 1980s. Within a few years, the rapid and widespread circulation of this easily disseminated medium had a huge impact on traditional entertainment and cultural censorship in China. It was not until many years later that we realised that some of the most renowned Taiwanese and Hong Kong arthouse films like City of Sadness (1989) by Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Days of Being Wild (1990) by Wong Kar-wai and A Brighter Summer Day (1991) by Edward Yang, had long since entered the mainland through the route of pirated videotapes disguised as Hong Kong commercial films such as John Woo‘s The Killer (1989) and A Better Tomorrow (1986). Meanwhile, mainland underground films (for example, Zhang Yuan’s 1993 film Beijing Bastards) that could not be shown in commercial cinemas returned to the mainland market through pirated videotapes soon after their release in Hong Kong.

The cultural sector of the government responded to this situation by encouraging the production of its own “films” to counteract and dilute smuggled and ripped tapes. In 1986, private or semi-state-owned companies and units began to produce their own videotape films in Changsha and Chengdu. In the context of mainland China, the so-called videotape film is a sub-genre of feature films. Typically around 90 minutes long, shot on BETA tapes (instead of 35 mm films used in state-owned film studios) and released in videotape format. This packaging of videotape films was designed to mimic the videotapes of imported Hong Kong films in order to allow them secret entry into the retail and rental markets, infiltrating video halls and even local television stations. Unlike the films made by professional state film studios, the production quality of videotape films was crude. Yet without the constraints of strict state censorship, they usually featured bizarre and unpredictable story lines[1]. The production of Chinese videotape films reached its peak in 1990-1992, but I am afraid it is difficult to count and verify the exact number that were produced.

However, with the widespread release of VCDs and later DVDs, videotape films and their culture faded away rapidly after the mid-1990s. The rise of cinephile culture also made it increasingly difficult for the ersatz videotape films made by unknown teams to compete with the highly recognizable Hong Kong and foreign auteur films. Videotapes began to physically deteriorate and disintegrate over time.

The 1990s saw a total decline in the Chinese film industry, with low production capacity and even lower quality. As a result, there is little collective nostalgia for 1990s films in China today. Already being marginal at that time, the videotape films produced between 1986 and 1992 are naturally forgotten and their physical existence was also indiscriminately erased. No information on these films has been recorded in any form. No research has been done on them as a part of Chinese film history and there are no entries of them on any internet film data networks.

In 2016, I made a film, a 16mm vampire film, but I couldn’t find a cinema willing to screen it. In order to show this and other 16mm and 35mm films, I opened my own cinema ‘On Kino’ in 2017. The following year (2018), I opened a video hall “On Analog”, where I mainly screen films on videotape and other analogue media.

It was whilst buying videotapes from the second-hand market that I discovered the aforementioned Chinese videotape movies. I began to salvage and collect these videotapes from various sources. Many are Chinese cult films[2] and I regard them as a precious part of Chinese cinema culture. When I organise and archive them, I subdivide them according to the content of the film: Southeast Asia, missing girls, female revenge, murder, etc. Among these videotape films, there are two categories in which I am deeply interested: the quasi-“Taiwan” and “Hong Kong” films made in Mainland. During the time of political isolation between the three regions, the mainland videotape filmmakers made a lot of bad movies that were set in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

2.

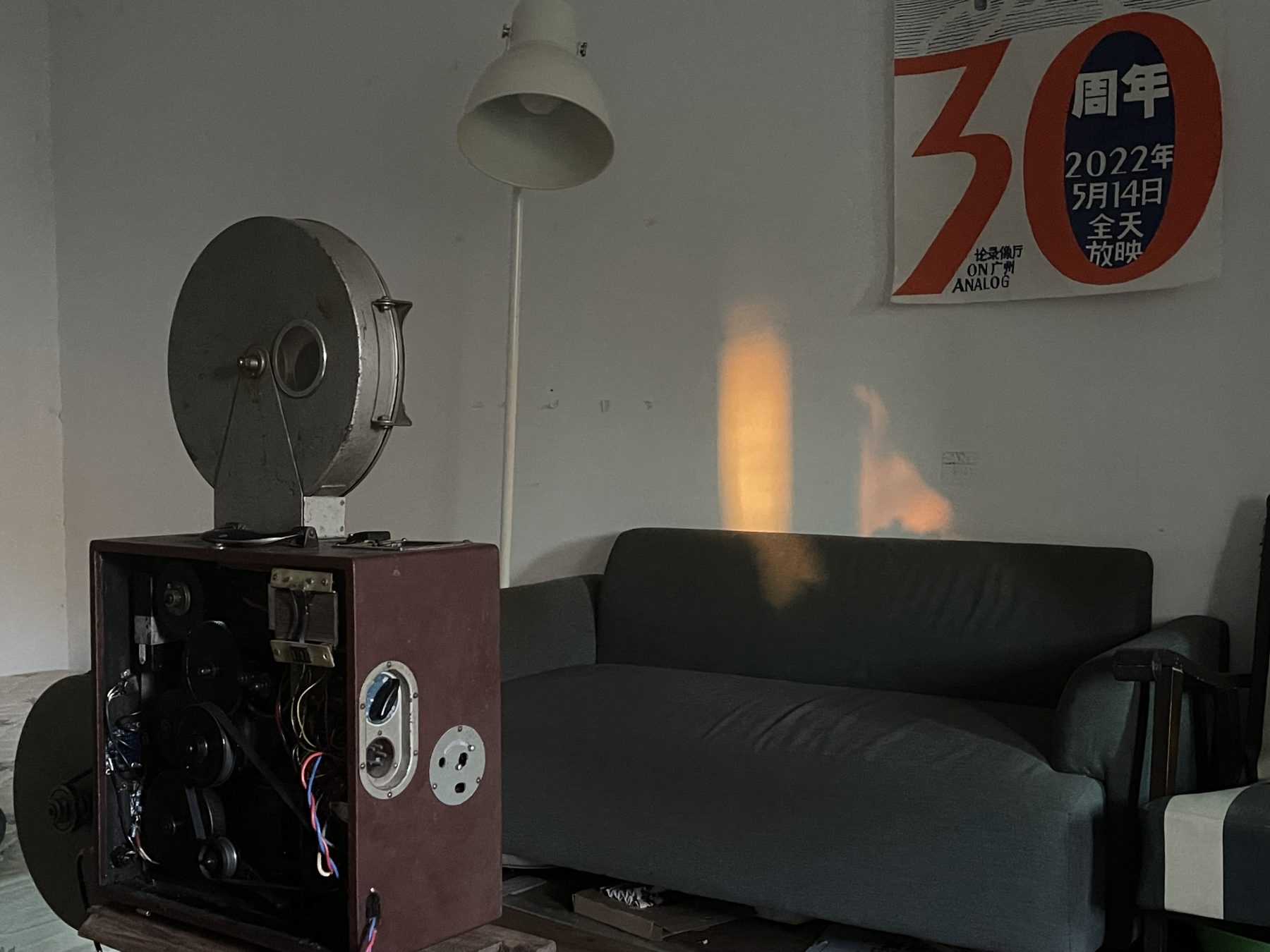

Film projectors and film copies met in the cinema and then parted with the advent digital cinema. But movie copies are always in circulation. Monumental cinema buildings will collapse and die, while movie projectors will cross mountains and oceans to reach places, with or without electricity, to show a movie.

I’ve told different friends many times about film projectors from mainland China being smuggled across the strait into Taiwan, although I’m too lazy to verify the truthfulness of the stories now. In fact, you may find the complete story by just typing in a few keywords on Google: projectionist, Jinggang Mountain, Hong Kong.

Fang ying shi (projectionist), a term used in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau, is called fang ying yuan in mainland China.

Jinggang Mountain was the earliest armed base of the Chinese Communist Party. The August First Film Machinery Factory in Shanghai, considered by Taiwanese projectionists to have a military background, produced a 35mm projector which was also given the name “Jinggang Mountain”. Jinggang Mountain projector used to be widely used in projecting films in the Mainland.

Hong Kong, prior to the opening of air links between the mainland and Taiwan, served as a transit point for cargo ships, travel and letter correspondence across the two sides of the Taiwan Strait.

In the early 1990s, a staggering number of Jinggangshan projectors were smuggled into Taiwan via Hong Kong to meet Taiwan’s market demand. At that time, there was a popular trend of hiring projectionists to show a film in private spaces despite the booming commercial film industry and the expansion of cinemas in general. Around 1990, two masterpieces of Taiwanese cinema were made: City of Sadness (1989) and A Brighter Summer Day (1992). I can’t help wondering if the two films, both of which are full of sorrow over Taiwan’s postwar history, have ever passed through the body of any Jinggangshan projector from the Mainland?

During the preparatory stage of ‘On Kino’, I had only one 16mm vampire movie in hand. The first movie was shown with a borrowed projector, which was owned by an old projectionist who lived in the same village as me. We only got to know each other shortly before the cinema opened, and actually it was from him that I learned how to operate the 16mm projector. It wasn’t until May 2022 that I purchased a wrecked 35mm Jinggangshan projector from a collector in northern China. The projector was in poor condition and had been remodelled. Again, it was the same projectionist who came to help me repair it. Two months later, I brought the projector to the city of Xining in the far west of China where I arranged a screening of a 35mm print of City of Sadness from the ‘On Kino’ cinema collection. Under this arrangement, the Taiwan film “re-enacted” its passing through the body of the Jinggang Shan projector. By the way, I’ve also spoken to different friends many times about how I got a copy of this film.

Chaozhou, Guangdong Province, is located just across the sea from Kaohsiung and Chiayi in Taiwan. In the early 1990s, Jinggang Mountain projectors were also popular in Chaozhou where even a lot of private individuals purchased the brand. Jianggang’s popularity surprised the August First Film Machinery Factory. The factory director even paid a personal visit to Chaozhou. I wonder what he saw and what he thought. The early 1990s was a transitional period when many state-run film studios were collapsing and the commercial film industry was not in good shape. Consequently, some previously stated-owned film prints began to flow into the hands of private collectors. Due to Chaozhou’s geographical and cultural ties with Hong Kong (many people in Chaozhou migrated to Hong Kong after WWII), copies of Hong Kong films were also smuggled into Chaozhou. A Chaozhou film collector once used his Jinggang Mountain 104 projector to show me a Hong Kong X-rated film Erotic Ghost Story (1990).

In 2019, I went to Chaozhou to visit a film collector. At the entrance of his huge shed-like warehouse, which was covered in dust and cluttered with films, I suddenly saw the words City of Sadness on one of the film cases. When I opened the case, I saw five kanji characters spelling “Tokyo Laboratory”, the famous Japanese film developing company, printed on the package.

This Chaozhou friend told me that this batch (of films) had come from Shanghai. I once heard that, in the 1990s, Mr. Hou Hsiao-Hsien used to give copies of his films to an organisation in Shanghai. Yet almost no one knew about it, and those prints were never screened.

There has yet to be a film made about the relationship and tension between the Mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan in the twenty-first century. I’ve always had plans to make a film in Taiwan, and I think it would upset a lot of mainlanders, Hong Kongers and Taiwanese.

3.

Watching open-air movies is a shared memory of several generations of Chinese people. The first movie I saw as a child [Nezha Conquers the Dragon King (1979)?] was no doubt an open-air movie as well. When I started writing this short article, I already had the ending in mind – a pale story of an open-air movie.

There have been countless people who have recalled in writing the story of the open-air movie, which has inevitably been romanticised. Even though someone wrote that he witnessed a brawl while watching an open-air movie, when he recalled this the fight had already blended into the movie. Or maybe he had forgotten about the movie that night and the fight was the only thing he remembered, and the fight became the movie.

However, not many people in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou or other big cities may have had the experience of watching open-air movies. Following the Cultural Revolution, the golden age of open-air cinema in remote rural areas ran throughout the 1980s. People in some villages may have only got to see one movie in an entire year. In the evening when the film projection team reached the entrance of the village, there were already many villagers waiting with their own benches to claim seats before dinner. The news would spread as the projectionist came, and some young people from other villages would travel to see the movie too.

In rural China in the 1980s, the general literacy level of farmers was still low and a movie could not necessarily induce people to think, let alone provoke discussions and reflections. Even some extraordinary movies might only remain in villagers’ memories for one day. When people meet up the next day, the conversation would usually go something like, “Well, the fight in last night’s movie was great.” The audience needed constant fighting and endless gun battles. In some small streets and towns with cinemas, open-air movies are occasionally shown in vacant lots. On such evenings, the audience is usually middle-aged and elderly people and children. While the cinema, on the other hand, is completely occupied by young people.

Those nights of watching open-air movies under the stars in the mountain villages, people didn’t care what movie is being shown, and no one asked the villagers what movie they wanted to see. One would not even bother to wait for the film projection team to arrive on a scheduled day. An open-air movie would come to the village by chance, by accident, and the villagers would gladly enjoy an evening of collective silence.

By the 1990s, a large number of movie theatres continued to close and fall into disuse because of the popularity of television and home video tapes, as well as the boom in video halls and other entertainment spaces. Rural youths went to work in economically affluent provinces and cities for better jobs, leaving their hometowns in the countryside. At this time, open-air movies found a new market: red and white celebrations. A projectionist may be asked to come over with equipment to show a movie on the evening of a wedding reception. An open-air movie would also be shown at the funeral of an old person. On these occasions, the audience would be smaller, and still no one cared what movie was shown. The projectionist would just decide what movie to show based on his own experience.

In the summer of 2020, I set foot in Northeastern China for the first time. I heard a recent story there which keeps surfacing in my memory. I keep wanting to claim it for myself and use it in one of my future movies. In the story, a high school principal hired a projectionist to show an open-air movie in front of his school as a celebration of his son’s admission to a good university. Yet there was not a single audience member that night so the projectionist showed the movie all alone. I hope my vampire movie may also have the honour of being projected in an empty place at night, cast into a void of darkness, without a single person watching.

Endnotes:

- For instance, in Crazy Ballroom (疯狂舞厅), a crime action film, several fashionable young ladies meet each other in a night club and decide to attack the mafia in order to rescue a famous female singer. Both the director and the cinematographer seemed to have ignored the presence of passers-by when filming external scenes. The locations and the passers-by are in stark contrast to the stylised fashions of the female protagonists. For me, the streets and the passers-by are the most exciting aspects of the film.

- For instance, in Asia God of War (亚细亚战神), virologist Gina was kidnapped during a UNESCO-invited trip to a fictive Southeast Asian country. Her Chinese female bodyguard Chen Feng and journalist Yumiko formed a special forces duo, setting out to rescue Gina from a Japanese war maniac called Honda Kumazo who has been hiding in the Philippine jungles since WWII. They also have to prevent Honda’s plan to launch a virus missile over the Pacificon Christmas eve. It was common in these films for stories to take place in a fictional Southeast Asian country, with made-up transnational military organisations in a subtropical jungle landscape. More interestingly, all westerners in this film, including Gina the Portuguese/Estonian virologist, who was supposed to be born in Macau according to the plot, were played by Uyghur actors.

Qin Dao is an artist, filmmaker and publisher based in Guangzhou, China.