Just a Movement

“Omar is dead!”, a voice cried out in Dakar, 11 May 1973. The eldest of the Blondin Diop family, a young militant philosopher, and the articulate Maoist in Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise had allegedly committed suicide in his Gorée Island prison cell. His family and friends did not believe a word of it, demanding that light be shed on this political crime. A phantom haunts the Senegalese capital, itself in a state of unrest.

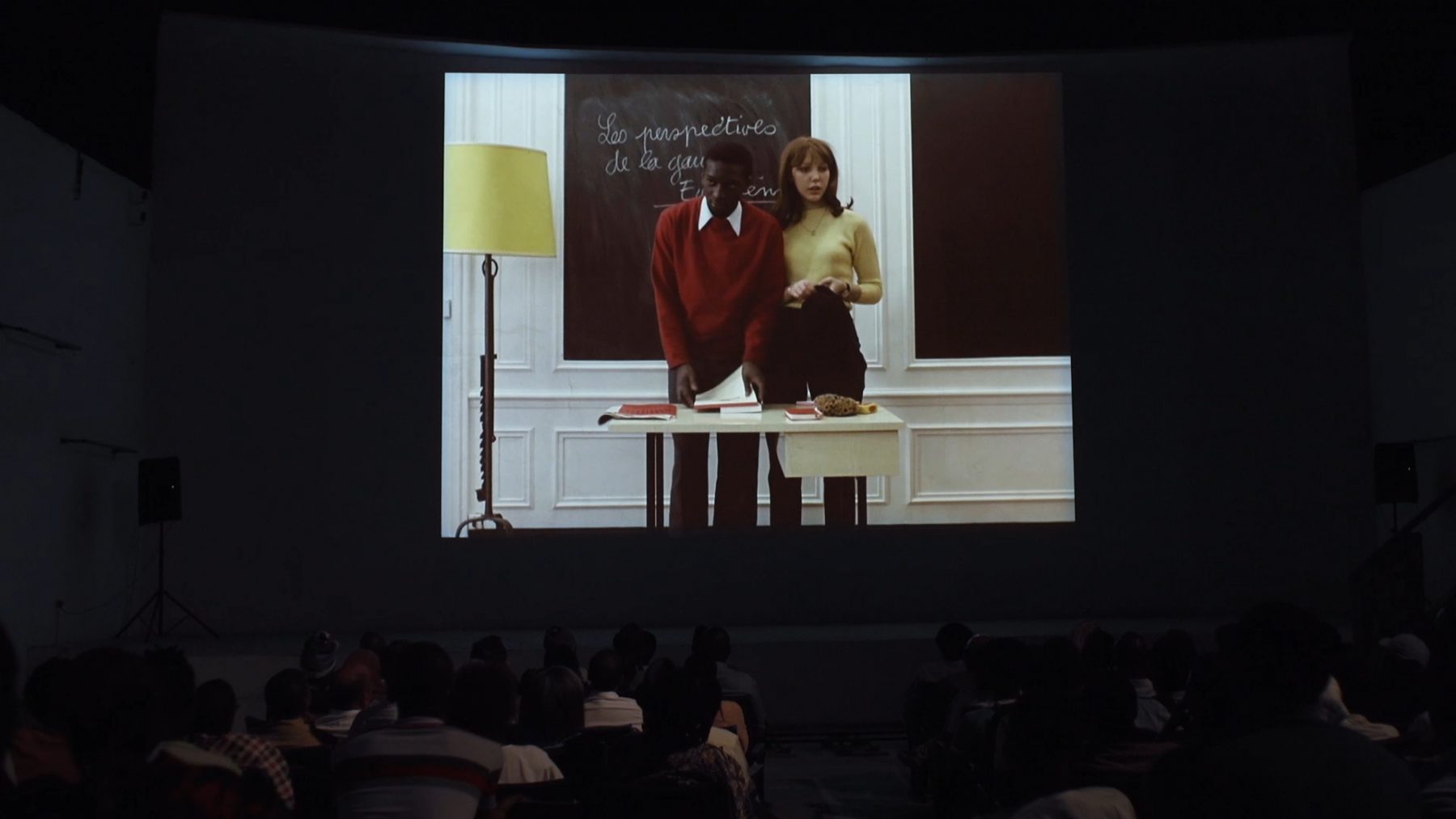

Juste un Mouvement, the last feature length film by the Belgian artist and filmmaker Vincent Meessen, is a free take on La Chinoise, a Jean-Luc Godard movie shot in 1967 in Paris. Reallocating its roles and characters fifty years later in Dakar, and updating its plot, this new version offers a meditation on the relationship between politics, justice and memory. Although not anymore alive, Omar Blondin Diop, the only actual Maoist student in the original movie, now becomes the key character. Shot exclusively with non-professional actors and including Omar Blondin Diop’s brothers and friends, everyone in this film performs themselves: a filmmaker, a rapper, a poet, a Chinese worker, a Shaolin master, a Senegalese intellectual, the Minister of Culture of Senegal and the Vice President of the People’s Republic of China.

In the course of this three-part conversation, Vincent Meessen and Olivier Marboeuf (who is one of the film’s producers) discuss the limits of documentary cinema, imagining the film as a space of justice and reparation always incomplete, question the speculative reconstruction of a memory and the alternative narratives of aesthetic and political Modernity.

Trailer : Juste un Mouvement (Just a Movement)

Translated from French by Melissa Thackway

PART I

A Cinema History

Olivier Marboeuf: Before coming on to your latest film, Just a Movement, which is also your first feature-length film, I’d like you to tell me a bit about your relationship to cinema. Yours is the path of an artist, but you’ve been making what I’d call “documentary-like film objects” for years now, in the form of museum, biennale, or art centre installations, but also increasingly for film festivals. I get the impression that it’s possible to retrace the genealogy of a cinematic gesture in your work, which has developed and grown stronger since at least Vita Nova, your 2009 film.

Vincent Meessen: Vita Nova, which was shot mainly in Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso, is based on the photo of a Black army cadet saluting the French flag published on the cover of Paris-Match in the mid-50s. The image much later became a kind of icon of Anglo-American postcolonial critique after Roland Barthes analyzed it in Mythologies. My film drew on the essay format and revealed Barthes’ previously covert colonial genealogy. The stake of the film wasn’t simply biographical, it was also critical; it highlighted the contemporary survivance of the colonial myth in images, postures, uniforms. It isn’t so much colonial history that interests me as history as a majority discourse invisibilizing all that it sidelines in its quest for territories to keep under the thumb and others to colonize and exploit. It was also a way of understanding that any artistic investigation, as soon as it de facto involves our modernity, forces us to apprehend all images as resulting from an operation of capture, that is, as an alteration of the reel and not just on an indicial mode – that of monstration – or an indexical mode – that of representation. Before Vita Nova, and in parallel with exhibitions in the contemporary art realm, I was quite present in festivals. Back in 2005, my first short film screened for the first time alongside Allan Sekula’s long-term research into the representation of workers in struggle. My film then won several awards, including the Oberhausen International Short Film Festival Grand Prize. It was shot with two workers from an artisanal mine on the outskirts of Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso. Adopting a documentary protocol that unfolds over time, into which little fictional details are inserted to make legible the question of the transfer taking place – mine, but also that of the two workers who, by excavating the earth brick by brick with a pickaxe, sculpt a form like a negative, a kind of inversion of the new town planned next to their worksite. A process of assemblage takes place between the documentary poetics, the critical investigation into land appropriation, and a tactic of disrupting realism inherited from conceptual art. I didn’t originally train as a filmmaker, but there were enough illustrious predecessors to lead me to think that cinema has to be made by anyone: Maya Deren was first a private secretary; Jean Rouch, a civil engineer; Ousmane Sembene, a docker and unionist; Jean-Luc Godard, a film critic; Marcel Broodthaers a bookseller and poet; Trinh T. Minh-ha, an ethnomusicologist, and so on. What is interesting are trajectories and self-transformations, not places and assignations. I don’t claim the identity of filmmaker as such, then – it’s more a role one takes on – but I am interested in the toolkit and the collaborative method, as I am in cinema’s role in the spectacular shaping of colonial modernity, that is to say, this matrix of power that we are tributary to in terms of discourse, archetypes, and logics of representation producing structural asymmetries that are still very present.

I use my artistic practice, including moving images, to experience the operability of certain methods and formal expressions depending on given contexts in order to activate certain potentialities that seem to me to be awaiting an urgent actualization.

OM: Your film turns cinema itself into one of its subjects by proposing a dialogue, and perhaps even a dance, with Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise, a fiction that was annunciatory of May 68, in which you, for your part, look for the traces of a documentary terrain.

VM: La Chinoise is a 1967 film in which a group of young people – a philosophy student, an actor, a country girl, and a foreign artist – shut themselves away in a bourgeoise Paris apartment for the holidays. They live under a “Chinese regime”, educate themselves with the help of Omar, a young philosopher, debate just ideas, the use of violence, and plan an attack on a Russian leader on a protocol visit to inaugurate a new building. Their aim is to trigger a hypothetical revolution in their own country. It’s an ambiguous film in which Godard critically portrays the spread of Maoism among French students, but also through which the filmmaker himself artistically confronts Althusserian thought, the Marxist philosopher whose influence was considerable at the time but who, due to his own dogmatism – and that’s the paradox of history – totally failed to recognize and accompany the May 68 uprising. Worse still, Althusser became the instrument to bring to heel the misguided communist youth. Althusser the intellectual guru, who interpreted the world instead of transforming it, was thus left behind by the students’ radical critique. Drawing lessons from this historic sequence can help us understand what is taking place at the moment. For, in its own way, capitalism has appropriated the rhetoric of yesterday’s doctrinal Marxists, and notably the sledgehammer argument of “historical and scientific necessity”, the new apparat of which is that of the digital “revolution”. Coming back to the question of documentary, I see it as a technique and an ethic of investigation that is precious and necessary to my work, but which I know is destined to be edited and to undergo the inevitable construction of a narrative. In cinema, it is customary to distinguish between fiction and documentary, which continue to be presented as opposing genres, when it is in fact more a question of a dialogic relationship, a complementarity that was induced right from the very birth of the medium. As I see it, La Chinoise shows many concordances with real events that took place a few years later, not only in Paris but in Dakar too, and which involved one of this fiction film’s actors. So, I closely examined this film, rightly considered to be a major work in film history. I approached it as the documentation, in words and images, of an experimentation in that it today above all speaks of its era, of the tensions within a Marxist constellation, and of insubordination. Furthermore, it contains almost the only moving images of Omar Blondin Diop speaking – a peripheral and a priori the least important character in the cast, whom I gave a leading role. Starting with this character as a nodal point, I devised a kind of interlacing that links this earlier film to mine. This ultimately creates a play, a spiral, allowing a circulation in an ascending and descending movement into the past and perhaps towards a future. This makes it possible to return to the past to grasp the impetus of the earlier film and to harness its potential energy again – that stored by a body – which can then be transformed into kinetic energy when this body is set in motion.

A portrait-in-absence

OM: Just a Movement‘s starting point is the tragic destiny of the young Marxist intellectual and activist Omar Blondin Diop. In one of your previous films, One. Two. Three., you already explored the connections between young students and the Situationist International, a Western revolutionary avant-garde that set out to occupy the cultural domain through its critique of the spectacle. How did you come across Omar?

VM: This film is indeed a direct prolongation of one of my previous films shot in Kinshasa as it was while doing research for that film that I came across the photograph of Omar Blondin Diop reading the final edition of the Situationist International journal. It happens that I’m particularly interested in the dissemination of situationist theses in Africa, an important subject for this revolutionary international avant-garde but one which is unexplored in the field of academic research. This film is a new contribution to this incomplete historiography, only not in written form, and its issues go beyond just the historical. In 2015, an associate identified the said photo of Omar as the source of a portrait painted by Issa Samb, a member of Laboratoire Agit’Art, a Dakar-based collective set up in 1974 and, to my mind, one of the most stimulating artistic adventures of African modernity. A photo thus led to a painting and suggested a direct link between artistic and political practice. Yet I already knew that while studying philosophy and preparing his agrégation exam, all the while being involved in student protests at Nanterre, Omar had played his own role in La Chinoise in 1967, a pivotal film in Jean-Luc Godard’s filmography. And lastly, Omar had also frequented the cinematic avant-garde in London and published an essay on a Warhol film. The combination of all these elements really sparked my curiosity. But it was the efforts undertaken by Omar’s family in Dakar to reopen the enquiry fifty years after his death in detention during Léopold Sédar Senghor’s presidency that convinced me that this story contained something topical and had memorial relevance nationally, and no doubt beyond. The aim, then, was to articulate the relation to not yet remembered pasts and to investigate their possible contribution to not yet imagined futures.

OM: Even though Omar’s suicide is called into question and uncertainties surround the circumstances of his death, Just a Movement isn’t really an enquiry in the criminal sense of the term, but rather a kind of political and poetic enquiry into the traces and the heart of Omar’s legacies. These legacies are in many respects speculative in your film, where you choose to focus on Senegal and its current struggles, and to propose a possible actualization of a phantom’s desires.

VM: It isn’t an enquiry into his death, but rather a film about his survival. My project was twofold from the start: firstly, to paint a portrait of Omar by listening to the relations lived, and thus to allow the Senegalese to be able to debate this figure, his legacy, and the meaning of his engagements anew. But being neither a historian nor a documentary filmmaker, it was important for me to reinforce this portrait-in-his-absence – and that can thus be qualified as spectral – with a cinematographic experimentation capable of connecting the projections and desires of yesterday with those formulated today. To be able, at the same time, to portray Chinese-Senegalese relations from Omar’s Maoist phase to the stakes of the current state’s bargaining with China, to sound out the young generation of militants’ relationship to the figure of political martyr, or again, to try to elucidate the way in which Omar embodies a blind spot in Godard’s cinema. Proposing a possible actualization of the phantom’s desires, as you suggest, is indeed to take seriously the survival of the dead, who continue to haunt a scene, whether artistic or political. It happens that Omar haunts both of these scenes like a tragic hero. He troubled both Senegalese politics under Senghor, of which the current authorities are the heirs, Godard’s cinema, or again the performances of Issa Samb and his Laboratoire Agit’Art peers.

OM: What is quite striking in the form too is the way that this portrait endeavor also espouses Omar Blondin Diop’s complexity and contradictions, freeing itself of the mirror form by choosing that of the crystal, which diffracts the gaze towards multiple trajectories, friendships, and temporalities. Omar is turned into a kind of vast territory that we explore, and which is recounted by multiple voices, translated, interpreted – in both the sense of an actor’s performance and an actualization.

VM: Out of all translators, interpreters are the ones who are capable of translating out loud, live, from one language to the next. Their work includes the performative dimension of live performance. We were indeed attempting to interpret rather than to translate as we freely improvised from a few key sequences of La Chinoise. Godard was constituting cinema as an experimental machine at the time, one intended no longer simply to interpret, but to transform the gaze and the world around him. It was with this film that he understood the need not for political film, but to film politically, that is, to deconstruct the whole process of making and distributing a film. And he has ever since remained faithful to this lesson he learned by working in his own way and with others.

My film mixes a form of interpretation with testimony so that, if we want to use an analogy, more than the reflections of a crystal, I’d say, rather, the intertwining of a complex knot, like those tried and handed down in string games in ancient times. In addition to creating abstract geometric forms, we know that these games, which are common to nearly all civilizations, were associated with mythical, utilitarian or situated tales. Every loop of the string, every movement, was memorized as a stage progressing in a narration. Cinema could be seen as the animation of these forms, like the actualization of the string play tradition and their pedagogy based on abstract motifs that are always related to a lived experience, a gesture, a body. I also used “string tricks”, or processes – mise-en-scene, montage – to weave together an existing film with a film-in-the-making in which the witnesses themselves knot together a figure who continues to inhabit them: Omar. They knew him in different circumstances and at different times of his very short life. While the film does respect a chronological progression in Omar’s trajectory, it is not necessarily linear; rather it adopts a fragmented temporality comprised of serpentine to-ing and fro-ing, loops that the dichotomies between the evocations of the past and a series of actualizing gestures leave open. The testimonies of those who intervene crisscross, complement, or sometimes contradict one another without anyone being able to pin down or grasp the individual. My film ends on the reiterating of the enigma concerning the multiplicity of this evolving character, which signifies that, ultimately, no one can possess Omar. With these interviews, we are thus in … “the inbetween”. All that has happened in common, and yet is always contested, generates a politics of memory.

Omar blondin diop (1946–1973) was a Senegalese militant leftist intellectual born in Niamey (Niger) and who died in prison on Gorée island (Senegal). As a student in philosophy in Paris during the 1960s, he graduated from the renowned university École Normale Supérieure de Saint-Cloud. Studying at the University of Nanterre, he met Jean-Luc Godard and “played himself” as a Maoist militant in La Chinoise (1967). A member of the Fédération des étudiants d’Afrique noire en France (FEANF), he also took part in the March 22 Movement. This French student movement occupied administration buildings at Nanterre University and was at the origin of the student uprising of May ’68. Diop was expelled from France to Senegal where he briefly was a researcher at the IFAN (Institut Fondamental d’Afrique noire), and founded the Mouvement des Jeunes Marxistes-Léninistes (MJML), a clandestine party. On presidential request, he was re-admitted to study in Paris on the condition that he would stop his political activities. Shortly after returning to Paris in 1970, two of his brothers were arrested and sentenced in Dakar. Omar left France to prepare his brothers’ escape, but was preventively arrested in Bamako.

Vincent Meessen was born in Baltimore, USA, in 1971, and lives and works in Brussels, Belgium. His artistic and filmic work are woven from a constellation of figures, gestures, and signs that maintain a polemical and sensible relation to the writing of history and the westernization of imaginaries. He decenters and multiplies gazes and perspectives to explore the variety of ways in which colonial modernity has impacted the fabric of contemporary subjectivities. Both in his work as an artist and filmmaker, he likes to use procedures of collaboration that undermine the authority of the author and emphasize the intelligence of collectives. His films have been screened at numerous museums and art centers including Centre Pompidou (Paris), HKW (Berlin), MUMOK (Vienna), Museo Reina Sofia (Madrid), in film festivals including IFFR (Rotterdam), IDFA (Amsterdam), Oberhausen International Short Film Festival, Art of the Real (New York, Seoul), FID (Marseille) and FESPACO (Ouagadougou).

Main solo exhibitions have taken place in Montreal, Toronto, Paris, Basel, Brussels, Bordeaux, Mexico, Amsterdam.

Vincent Meessen has represented Belgium at the 56th Venice Biennale with Personne et les autres, a group show with ten invited artists from four continents. Recent other biennale participations include … and other such stories, Chicago Architecture Biennial, (2019); Généalogies futures, récits depuis l’Équateur, Biennale de Lubumbashi (2019); Proregress, 12th Shanghai Biennale (2018-2019); Printemps de septembre, Toulouse (2016, 2018) and Gestures and Archives of the Present, Genealogies of the Future, Taipei Biennale (2016).

Vincent Meessen is a member of Jubilee-platform for research and artistic production.

Credits

Juste un Mouvement (Just a Movement)

a film by Vincent Meessen (color, 108 min, 2021)

Coproduction BELGIQUE / FRANCE : JUBILEE / Vincent Meessen et Inneke Van Waeyenberghe, THANK YOU & GOOD NIGHT productions / Geneviève De Bauw, SPECTRE productions / Olivier Marboeuf, CBA – Centre de l’Audiovisuel à Bruxelles / Javier Packer Comyn, MAGELLAN Films / Samuel Feller

With the support of: Centre du Cinéma et de l’Audiovisuel de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles , Service public francophone bruxellois, Vlaams audiovisueel fonds (VAF) et CNAP-Image/Mouvement, Centre Pompidou, Paris Mu.ZEE, Oostende, 34a Bienal de São Paulo Art et Recherche, Région Ile-de-France, Région Bretagne, Argos Centre for audiovisual arts, Belgium Federal Government Tax shelter

All informations about the film : https://justeunmouvement.film/#introduction