Non Aligned Film Archives

The restoration of an archive most frequently evokes the idea of a physical operation that allows the archive to be brought back to its initial form as closely as possible. But what of film archives that have disappeared for political reasons or become damaged in the margins of a dominant history of cinema and its accompanying industry? In this case it becomes possible to imagine not just a restoration, but a reparation, as a gesture that renounces the path backwards in favor of imagining another future based on the traces left by the work, its scars, the voices and lives that inhabit it and all their narrative potentialities. The act of reparation thus becomes a way to invent a new form as much as a new space for reception. A new life.

Through their joint conversation, Annabelle Aventurin and Léa Morin trace paths towards reparative practices of non-aligned archives. The re-circulation of minority works becomes here an act of reassembling fragments of knowledge, of small and large histories, of disregarded geographies and relations. Far from any fetishism for rare objects, this reappearance renews the art of showing films by giving it the potentiality of a veritable ritual of political recomposition. In the present, this act revitalizes endeavors, wild ambitions, radical gestures and a plethora of dreams of a revolution that is always to come. The revolution of cinema as witness and inventor of a society.

Olivier Marboeuf

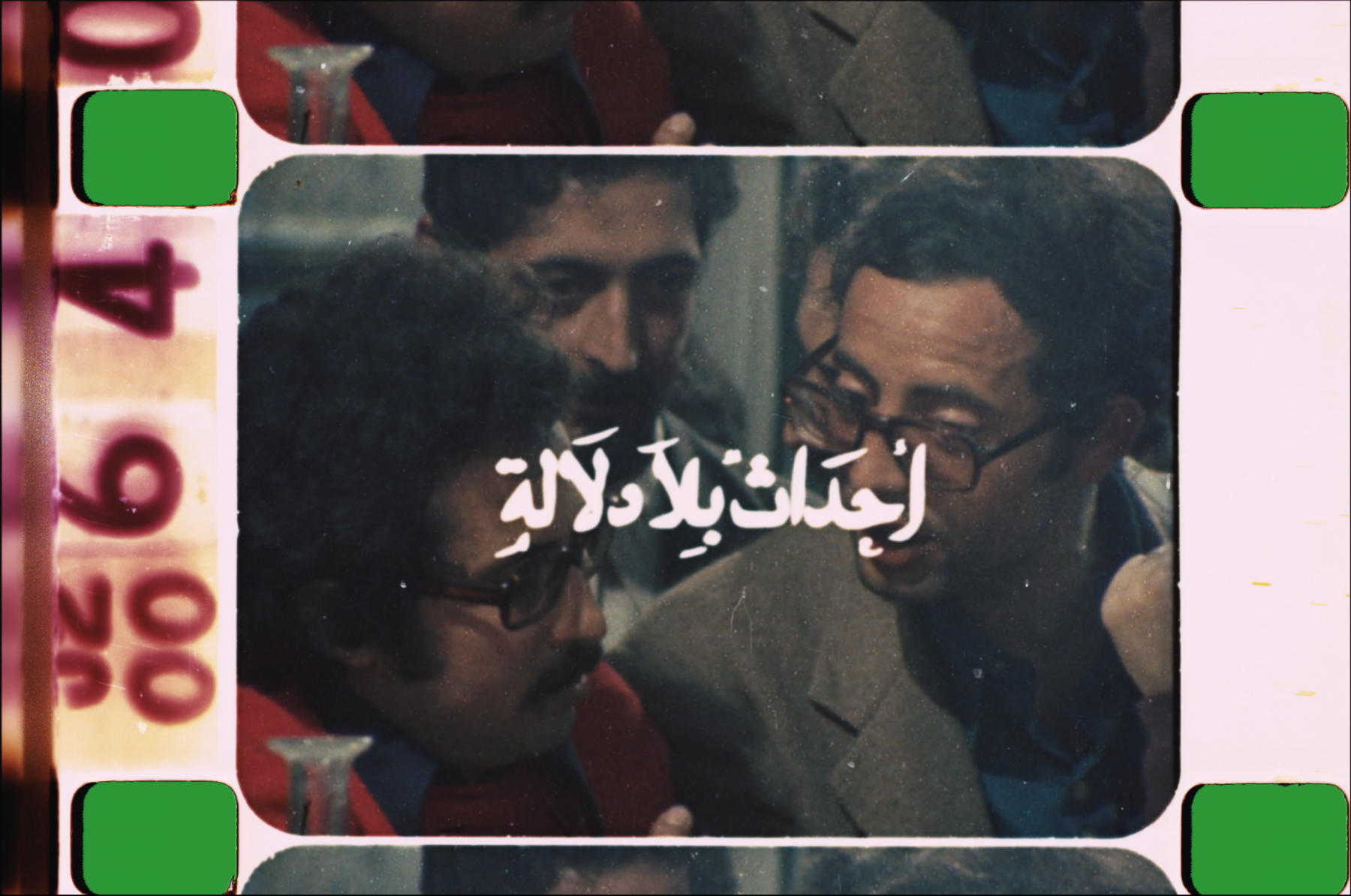

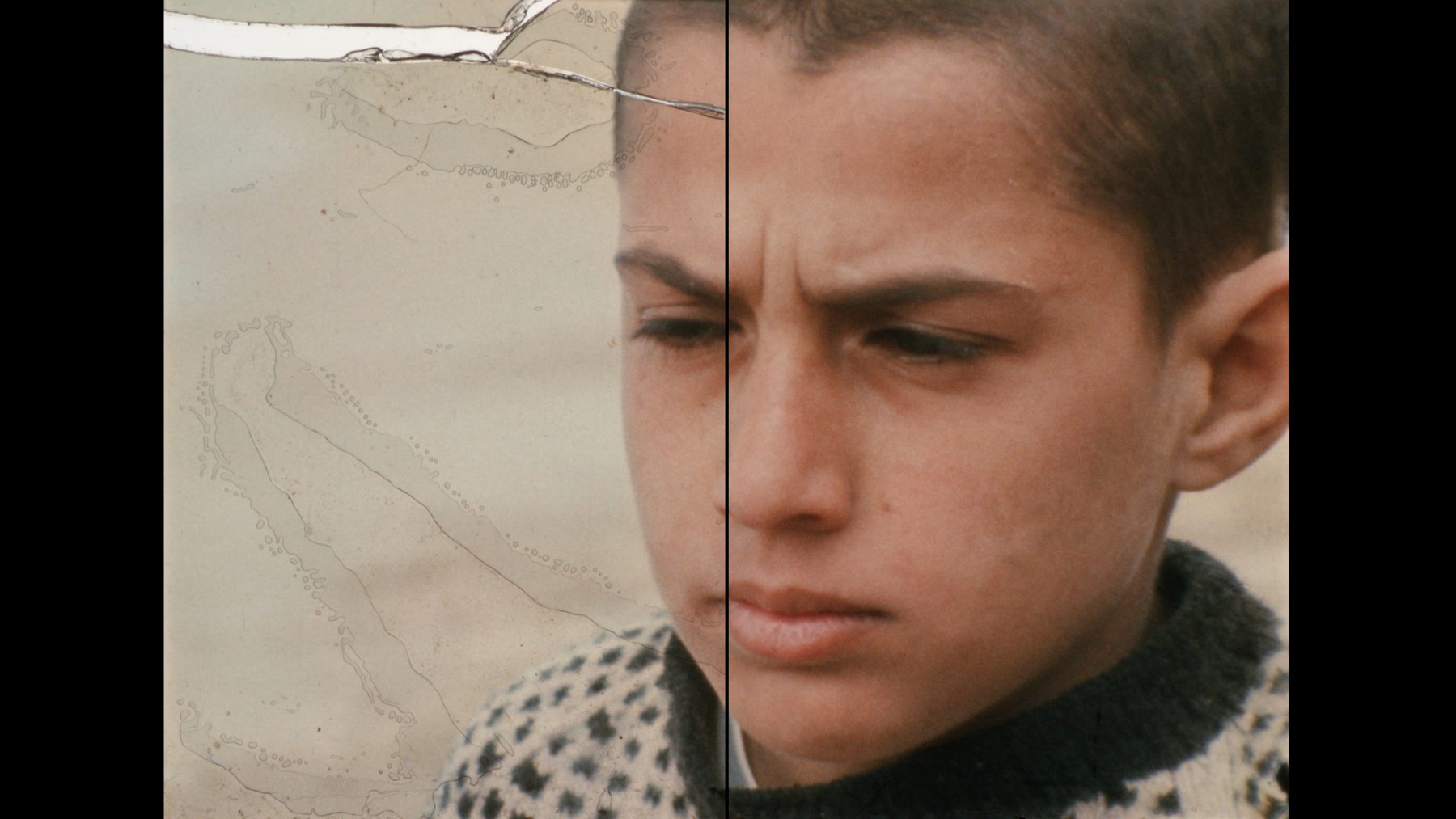

Screen shot of a digital file from the film On Some Meaningless Events (Mostafa Derkaoui, 1974) © Filmoteca de Catalunya, 2018

Annabelle Aventurin is responsible for the conservation and distribution of Med Hondo’s archives at Ciné-Archives (an audiovisual collection of the French Communist Party and the workers’ movement). In 2021 she coordinated, with the Harvard Film Archive, the restoration of West Indies, 1979 and Sarraounia, 1986. She is also a film programmer and is currently finishing her first documentary film.

Léa Morin is an independent curator and researcher. She is engaged in projects of editing, exhibition, film programming and restoration that bring together researchers, artists and practitioners. She is especially interested in the circulation of ideas, forms, aesthetics, and political and artistic struggles in the period of independence movements (1960s and 1970s) and in the stakes of cultural decolonization. She is also part of the team “Archive Bouanani, a history of cinema in Morocco” in Rabat, and “Talitha” devoted to alternative and experimental cinematic and sound archives, preservation, and redistribution in Rennes. www.talitha3.com

A discussion about our crossed practices of reconstitution and circulation of “non-aligned” film archives…

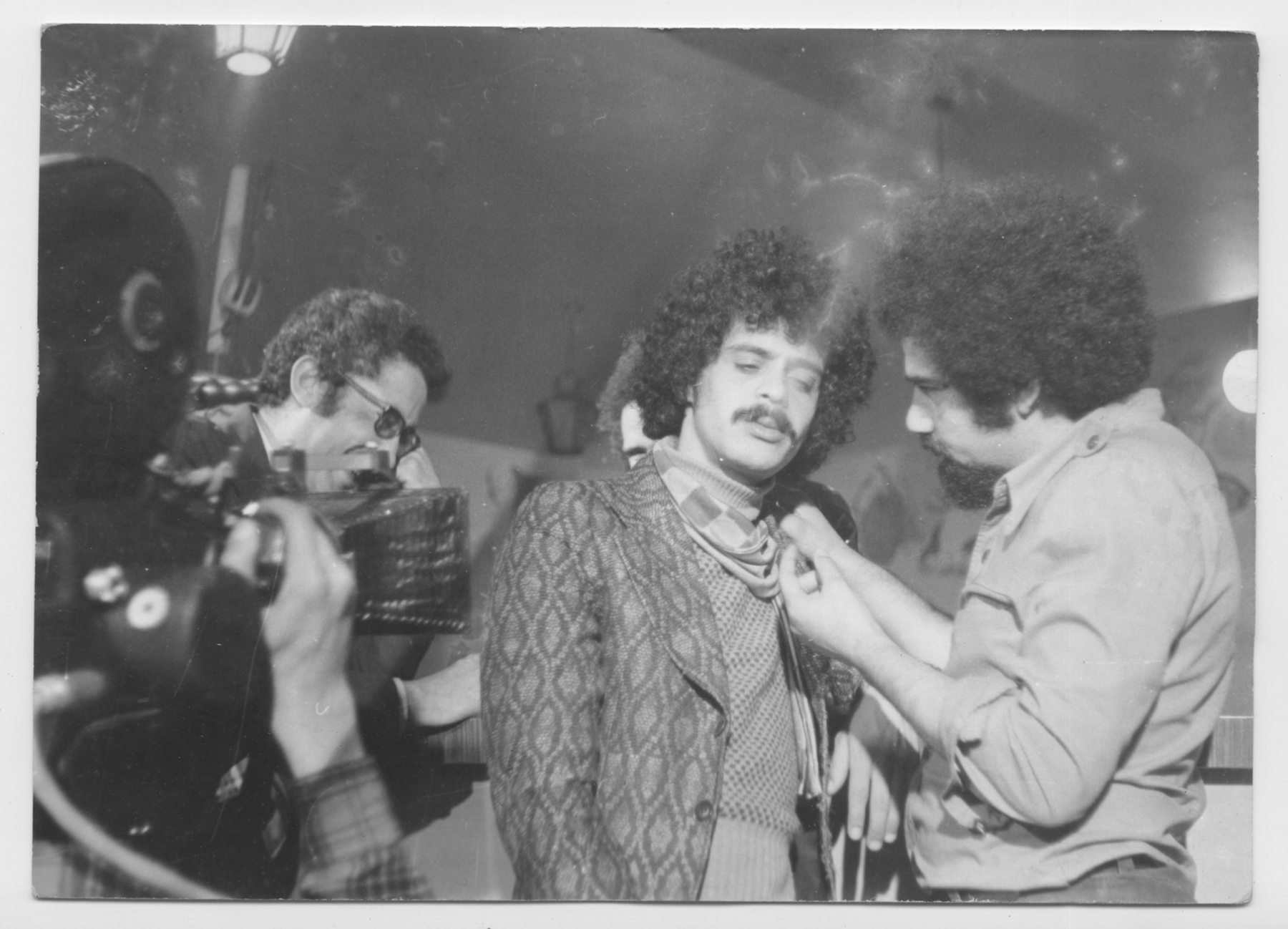

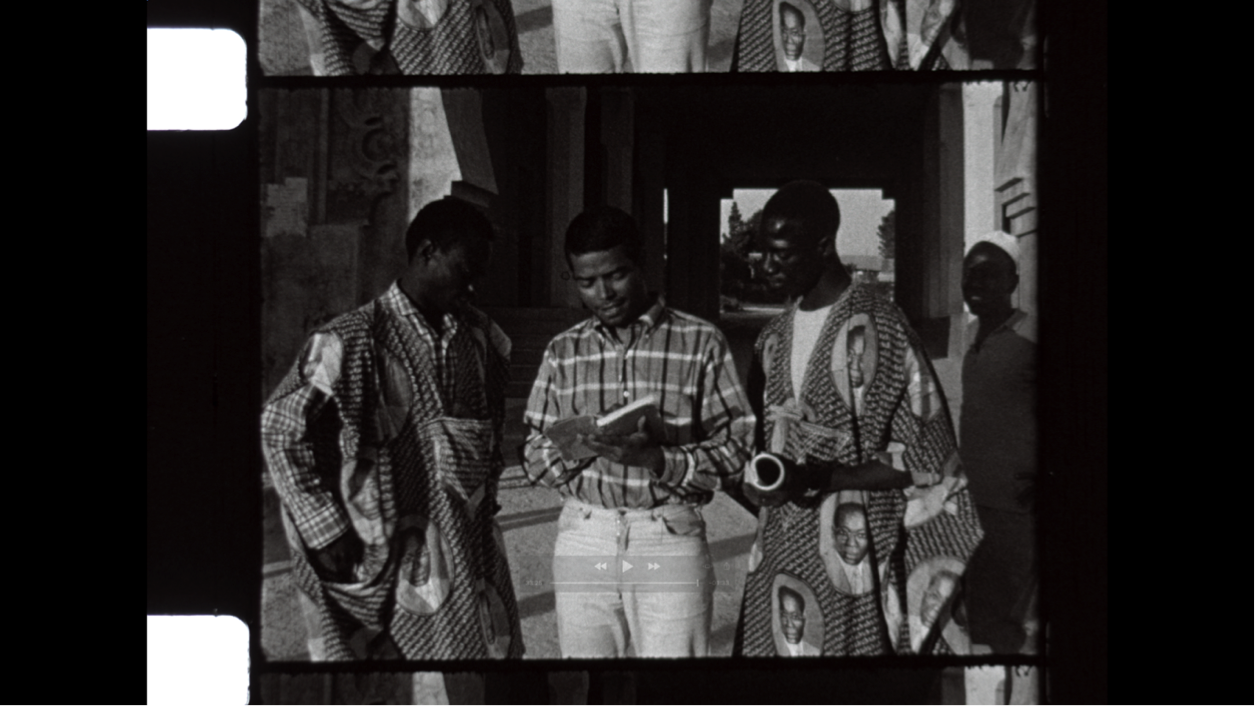

Photo from the film shoot of Mostafa Derkaoui’s On Some Meaningless Events, Casablanca, 1974, Krimou Derkaoui Archives.

Annabelle Aventurin: You could say that our processes have crossed paths. As part of my work, I’m led to begin work using physical elements, whether these are films or documents, (photos, screenplays, lists of dialogue, financial dossiers, etc). Whereas when you begin research on a film, sometimes you don’t have access to any viewable copy, or no original elements have been identified, or no document at all is accessible…

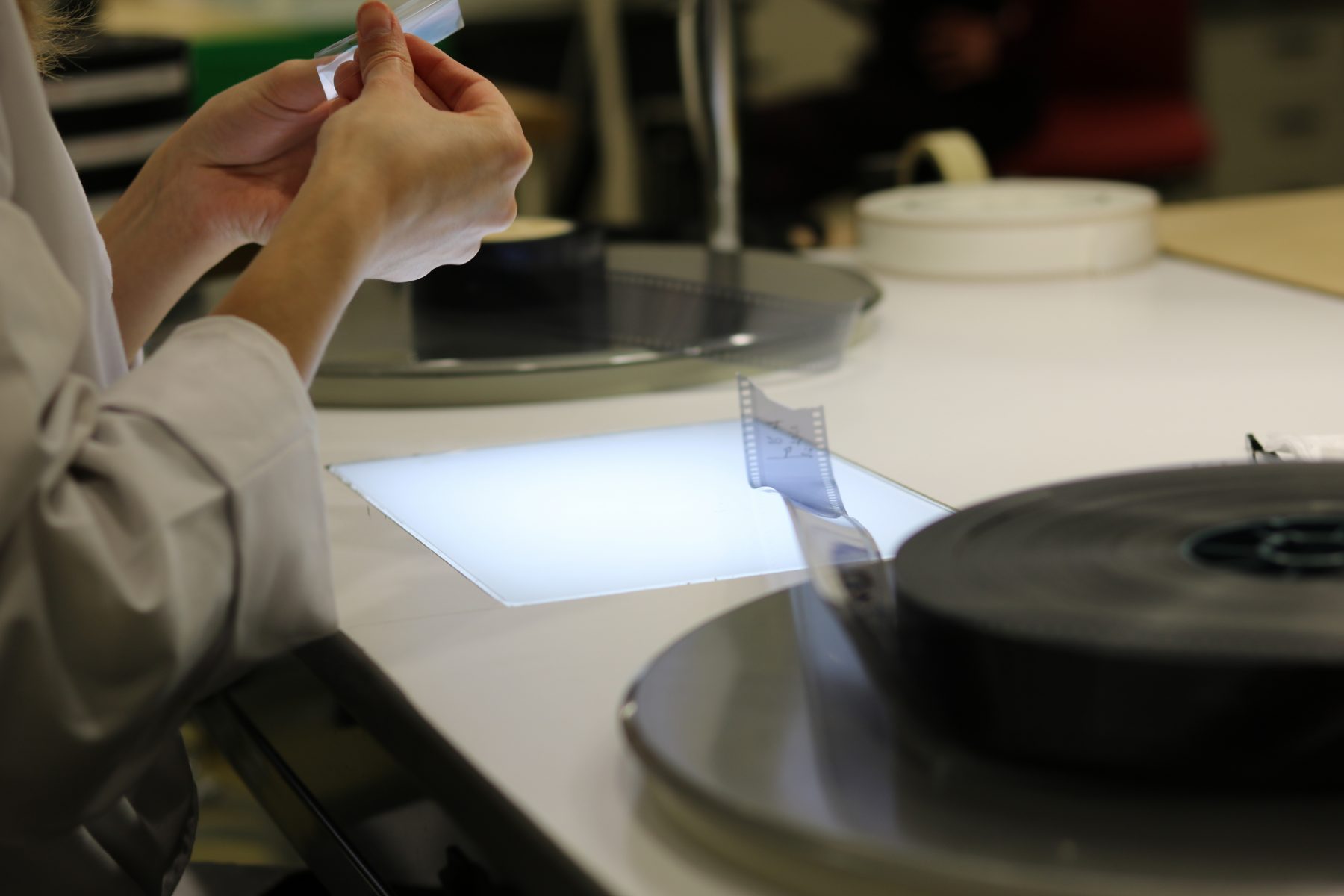

Léa Morin: Yes and furthermore, the absence and invisibility of these films or cinematic narratives is often my subject of initial research. This means exploring and investigating their disappearance as an entry point for a reflection on the historiography of film. And to try to reconstruct them through absence. But when you work on a film for months or even years, conducting interviews, searching for traces, exploring each micro-story pertaining to its fabrication and then suddenly, in the middle of this investigation, you locate the original elements: you can’t stop there. That’s what happened with About Some Meaningless Events (Morocco, 1974, Mostafa Derkaoui[1]. When I received for the first time a photograph of the 16 mm negatives identified by the teams of the Filmoteca de Catalunya in Barcelona, all of a sudden, in the literal materiality of the physical film, I realized (or I imagined) that the tensions that traverse Derkaoui’s film were apparent on the film reel. The incredible elan of this collective of filmmakers, artists, and actives, united for an extraordinary film shoot in the streets of Casablanca in 1974, driven by the desire to create a new cinema, a clearing of frontiers between creative disciplines, a reflection on the political power of film. A unique experimentation, innovative and avant-gardiste, which unfortunately was ended by a ban on distribution. And then oblivion. Restoring this film, making it visible again, respecting the intentions of the author, is an attempt to restore a missing aesthetic and political history. It’s trying to take into account the damages and gaps of a History of cinema. It means reactivating the incredible and almost insane hopes that this band of dreamers and militants invested in the film (for society and for an invention of forms freed from colonial domination). Hopes for nothing less than a cultural and political revolution. Looking at the film reels, looking at the footage of film, you find yourself face to face with the concrete materiality of a (hi)story. It’s quite staggering to realize it. You cannot conduct a restoration project without having reconstructed the itinerary, the history of this physical film, its production and distribution, and often these are extremely complex and significant trajectories…

________________

[1] Film digitized and restored in 2018 by the Filmoteca of Catalunya, in partnership with the Observatory (Casablanca)

At the Filmoteca in Catalunya, during the restoration of Mostafa Derkaoui’s film On Some Meaningless Events, photo Léa Morin, 2018.

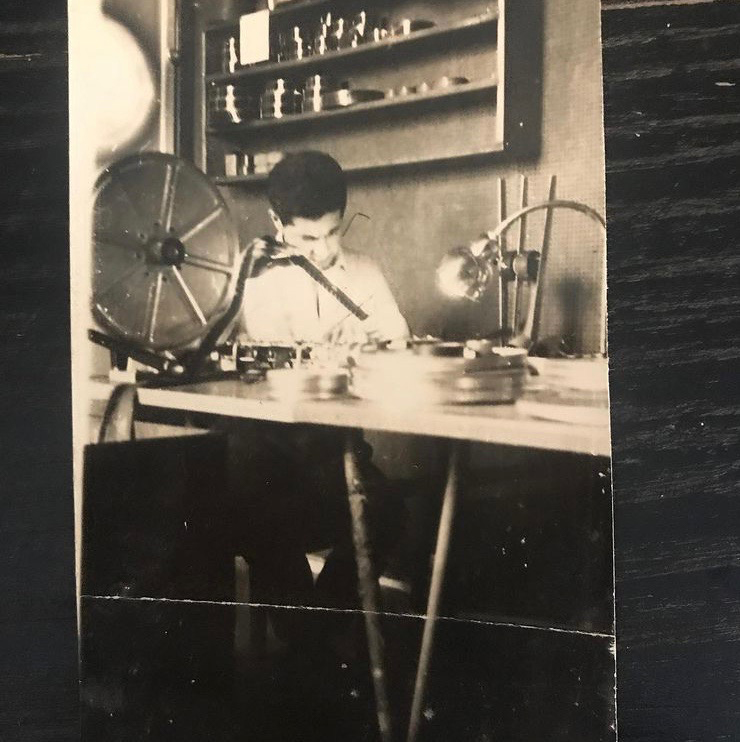

Allal Sahbi during editing of Latif Lahlou’s film Soleil de Printemps (1969, Morocco), archives of Latif Lahlou.

AA : To understand a collection, it’s important to reconstruct an itinerary, as you indicated. Keeping the filmmaker’s trajectory in mind is also necessary. Med Hondo, for example, was born in 1936 in Atar, Mauritania; he left his native Sahara in 1955 and studied at the hotel management school in Rabat. In 1958 he arrived in Marseille and then moved on to Paris, where he began to study the dramatic arts, while continuing to work in restaurants. He followed the itinerary of an immigrant in France. It’s important to keep that in mind because he would always make films for and by Africans, dealing with themes linked to the history of Africans and African diasporas across the world.

And consequently, he maintained this approach in the production of his films. West Indies (1979) was the result of an inter-African co-production between Algeria, Mauritania, Senegal, and Ivory Coast. Sarraounia (1986) was for the most part financed by Med Hondo’s production company, les Films Soleil Ô and with the support of the Burkina Faso government of Thomas Sankara.

The physical cartography of his films reveals that they are all preserved in France. Exploitation copies can be found in other countries, but the elements of heritage (sound and image negatives, interpositives, sound mixing) remain in France. For the most part, Med Hondo’s films received commercial releases in France, often with difficulty. His cinema is also part of a history of the film industry in France. Sarraounia received a very limited commercial exploitation in France. A petition so that the film could be re-released was organized and signed, among others, by Ousmane Sembene, Costa Gavras, Souleymane Cissé and Jacques Demy. The film discreetly appeared in cinemas in 1992 but never obtained the commercial release it deserved.

Film reels of West Indies, conservation storage space at Ciné-Archives, photo Léa Morin, 2019

LM: For Mostafa Derkaoui’s film, we can trace a fascinating cartography : the physical film came from Eastern Europe (where he studied cinema), development was done in Madrid, editing in Casablanca, but also in Rome, where the Derkaouis were editing another film made in the interim in Irak for the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization), the film was blown up from 16mm to 35 mm in Barcelona, sub-titles were done in Paris, the first clandestine screening was at the pan-African festival of Khouribga in 1977, a 16mm copy was found in Mostafa’s attic in Casablanca…all of this leading up to restoration of the film in Barcelona and screenings all over the world. The film finally found its rightful place in the History of cinema, 45 years later. And every stage on this journey has its significance. All of this is absolutely not linear. The filming itself was done in several stages (the time needed to find additional financing, as well as to skirt difficulties with authorities). There was an equally fragmented story behind the creation of a film like Les Bicots-Nègres, vos voisins (Arabs and Niggers, Your Neighbors) (1974).

AA : Yes, totally. Med Hondo began filming on Bicots-Nègres just after shooting Soleil Ô (1970). That film shoot lasted three and a half years. The film originally ran at 2 hours 40 minutes. And it was this version that was presented at the International Festival of Young Cinema in Hyères (France) and which won a prize at the Journées Cinématographiques in Carthage in 1974. Med Hondo edited a new version of the film at the beginning of the 1980s, which runs at 1H40. An additional scene was filmed in 35 mm, while the rest of the film was shot in 16 mm. The film was re-edited and the sequences filmed inside the Croix Nivert foyer for immigrant workers in the 15th arrondissement of Paris were reduced. This same passage constitutes the short film Mes Voisins (My Neighbors) (1971).

LM : And so what is the status of Mes Voisins ? How does it fit into the filmography of Med Hondo ?

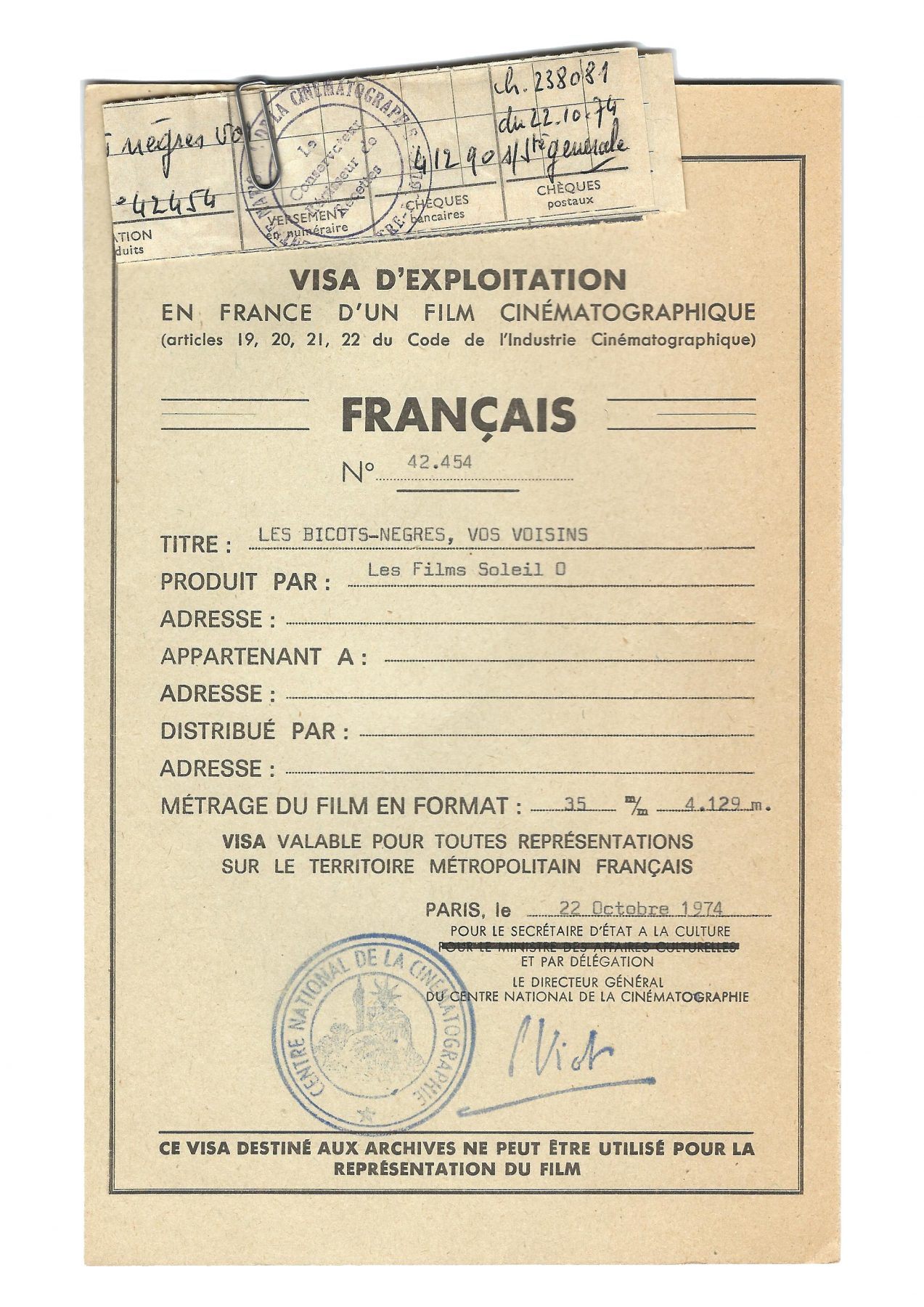

AA : It’s quite amazing. The exploitation visa (an administrative authorization necessary for any film released in cinemas, regardless of origin, French or foreign) for Bicots-Nègres, vos voisins in October 1974 indicates a 4129 meter film in 35 mm, which corresponds to the 2H40 version. The RCA (register of cinematography and audio-visual) indicates that Mes Voisins was listed on the same visa number in February 1974, in other words several months before the release of BNVV. And yet, exploitation copies of the mid-length film Mes Voisins exist. The film is 375 meters long in 16 mm according to the metrics indicated on the site dedicated to the distribution of films from Arsenal – Institut für Film und Videokunst, which corresponds to its run time, a half hour. In 2019 when the Berlin institution embarked on the restoration of Mes Voisins, they worked using original 16 mm negatives from the 2H40 version of Bicots-Nègres, vos voisins, preserved at Ciné-Archives, but also with the 16 mm exploitation copy in their possession and which served as a reference. It was presented at the first official edition of the International Forum of New Cinema during the Berlinale in 1971. It seems to me that it is thanks to this important programming work of the Forum section of the Berlinale that the impressive film collection of Arsenal began to be constituted. And finally, Mes Voisins has no exploitation visa in France which indicates a circulation within the network of non-commercial screenings. The film relates the struggle of workers in the Croix Nivert foyer in the 15th arrondissement of Paris to obtain better lodging. This struggle was central to the construction of the film BNVV.

Visa d‘exploitation de Bicots Nègres vos voisins Exploitation visa for Bicots-Nègres, vos voisins (Med Hondo, 1974) © Ciné-Archives

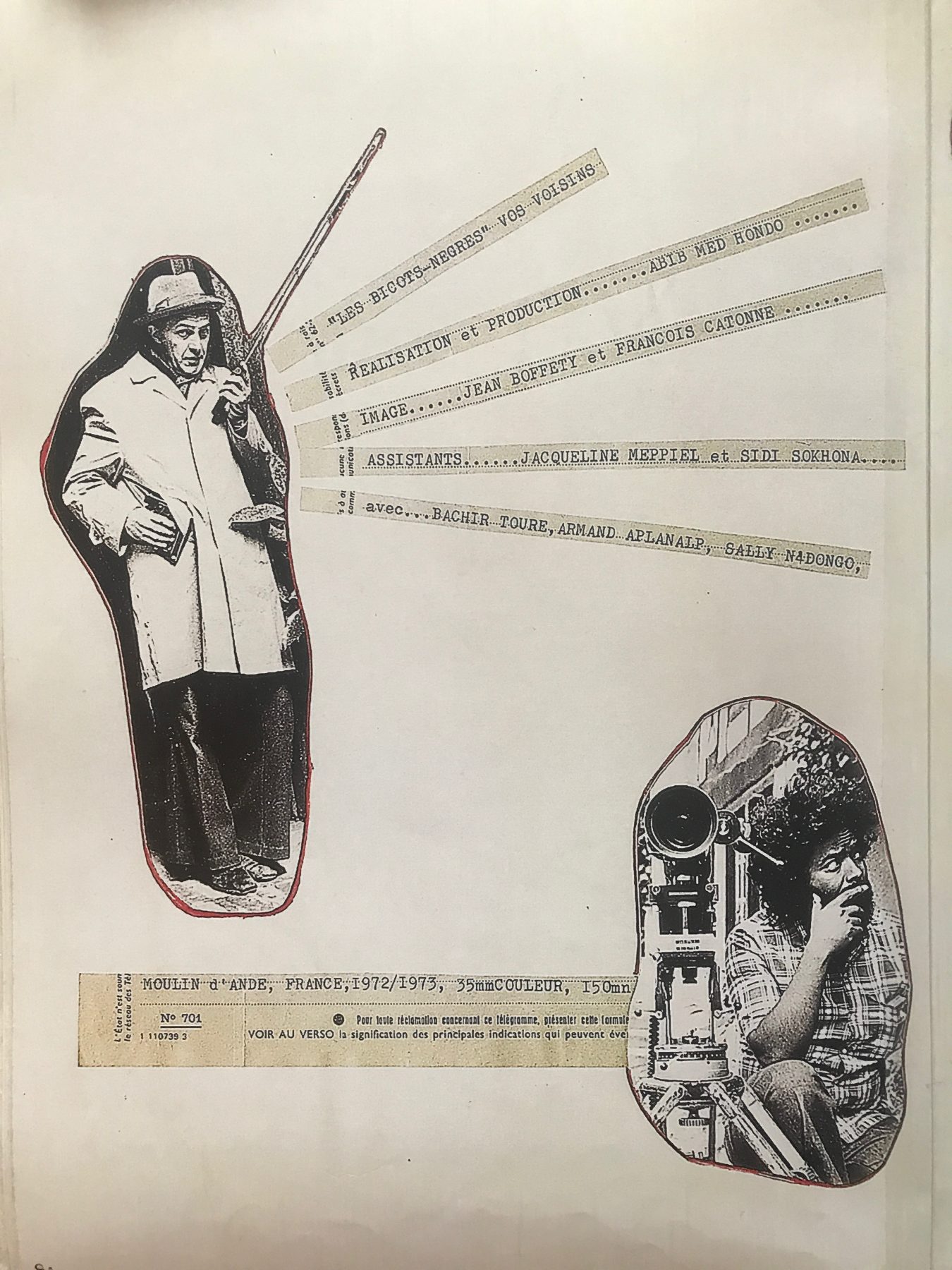

Montage on Med Hondo’s film Bicots-Nègres, vos voisins (1974), visitor’s book conceived of and created by Maurice Pons © Moulin d’Andé

LM : Research and programming are entry points. When you work on the oeuvre of a filmmaker who was unable to make the films he wanted to make (because his artistic vision did not align with the one his country desired, post-independence, and he was obliged to confront social and political realities), you find yourself trying to find his “potential” cinema in his student works, his first attempts. For example, in the case of the impeded Moroccan filmmaker Idriss Karim (who collaborated with the sociologist Paul Pascon on a film that has vanished, Les Enfants du Haouz/The Children of Haouz (1970), it was at the film school in Lodz (Poland) (where he studied in the 1960s and 70s) that we found the traces of what this lost film could have been. And this research also permitted the restitution of a missing history: that of transnational circulations (in particular between Africa and Eastern Europe) and their influences. These circulations also concern Algeria and it policy of co-production, Morocco which welcomed Senegalese films into its film laboratories, without forgetting the role of national ciné-clubs, places for screening of tri-continental films (Africa, Asia, and South America) or international festivals such as Khouribga, Carthage, or the Fespaco.

AA : Yes ! That makes me think of the CAC, the African Committee of Filmmakers. In 1981, Med Hondo, alongside filmmakers such as Haile Gerima or Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, took part in this organization whose mission was to promote African cinema in Africa and to fight against the distribution of Western and European devalued images in cinema. With the other members of the group Med Hondo sought financing for the translation of films in Arabic, organized the first international conference on cinematic production in Africa in 1982, as well as animating networks for intercontinental distributions. Sarraounia was screened in Mozambique, Niger, and Angola. Bicots-Nègres, vos voisins, Soleil Ô, and West Indies were shown in Mauritania. Having access to his archives decentralizes a western vision of cinematic exploitation and this is necessary.

LM : The non-film archives that you have at Ciné-Archives inform us about the circulation of works and allow us to learn a bit more about the way in which Med Hondo wanted to show his films, about his militantism as to including them in the industry of French cinema in order to remove them from the margins, as well as his fight for the development of an industry on the African continent… These archives also allow us to try to understand his desire behind all of these versions, like multiple iterations of a single film…

AA : Yes, it’s sometimes incomplete. For example, in the case of Bicots-Nègres, vos voisins, I know that the 2H40 version was also presented in Belgium at the time because a 35 mm copy is preserved at the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique in Brussels. In the paper archives, I have a document that indicates that the film was distributed as part of a program of films from Mauritania in 1981 and yet I’m not able to say if it was the re-edited version from the early 1980s that was shown.

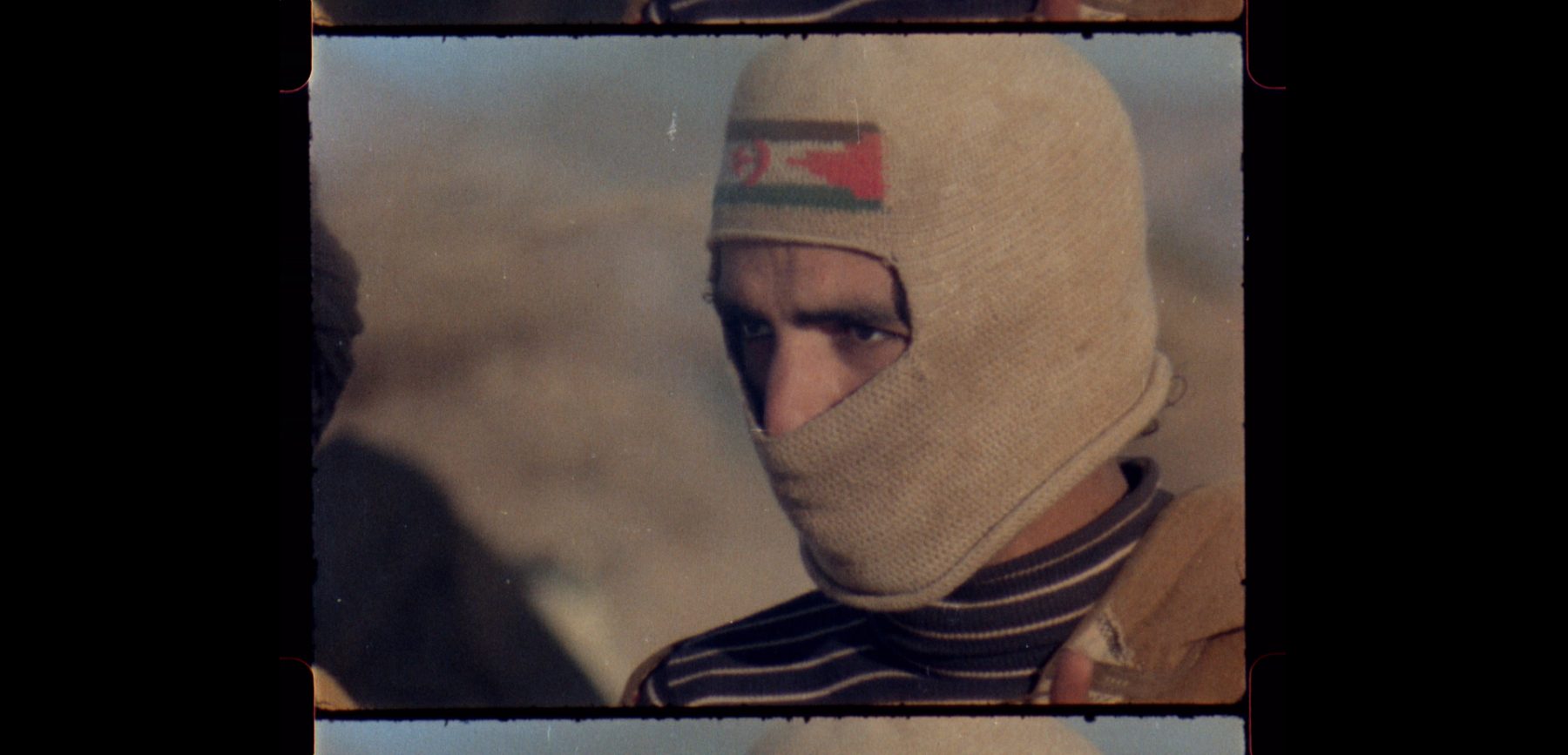

In any case, in my view the re-editing of this film indicates a desire to re-actualize the discourse and message of the film, to fragment it so that it could circulate again. And in fact Med Hondo made Nous Aurons toute la mort pour dormir/We willl have all death to sleep in 1977, a partisan film that follows the struggle of the Sahraouui people in the Western Sahara; he re-edited the film in 1978, which became Polisario, un peuple en armes/Polisario, a People in Arms, a shorter version, destined for a larger circulation in cinemas.

At Ciné-Archives I have the possibility to digitize 16mm film with our scanner. And so I’ve embarked on the digitization of the 16 mm negatives of Bicots-Nègres, vos voisins, corresponding to the 2H40 version, which was not the final version of the film. Even if the question of the version can be contextualized, the question of sub-titling remains. In the 1974 version, long sequences in Arabic, as well as other languages that I have not yet identified, are not translated in voice over, as opposed to the 1980s version, which is completely translated. In the paper archives at my disposition, I haven’t found any corresponding sub-titles. In consequence, translating these passages would certainly modify the intention of the author. I think that the question of sub-titles must also be asked concerning Djouhra Abouda and Alain Bonamy’s film, Ali in Wonderland (1976)[2].

________________

[2] Restoration and digitization 4K at the Image Retrouvée laboratory in 2021, in collaboration with Talitha – Rennes)

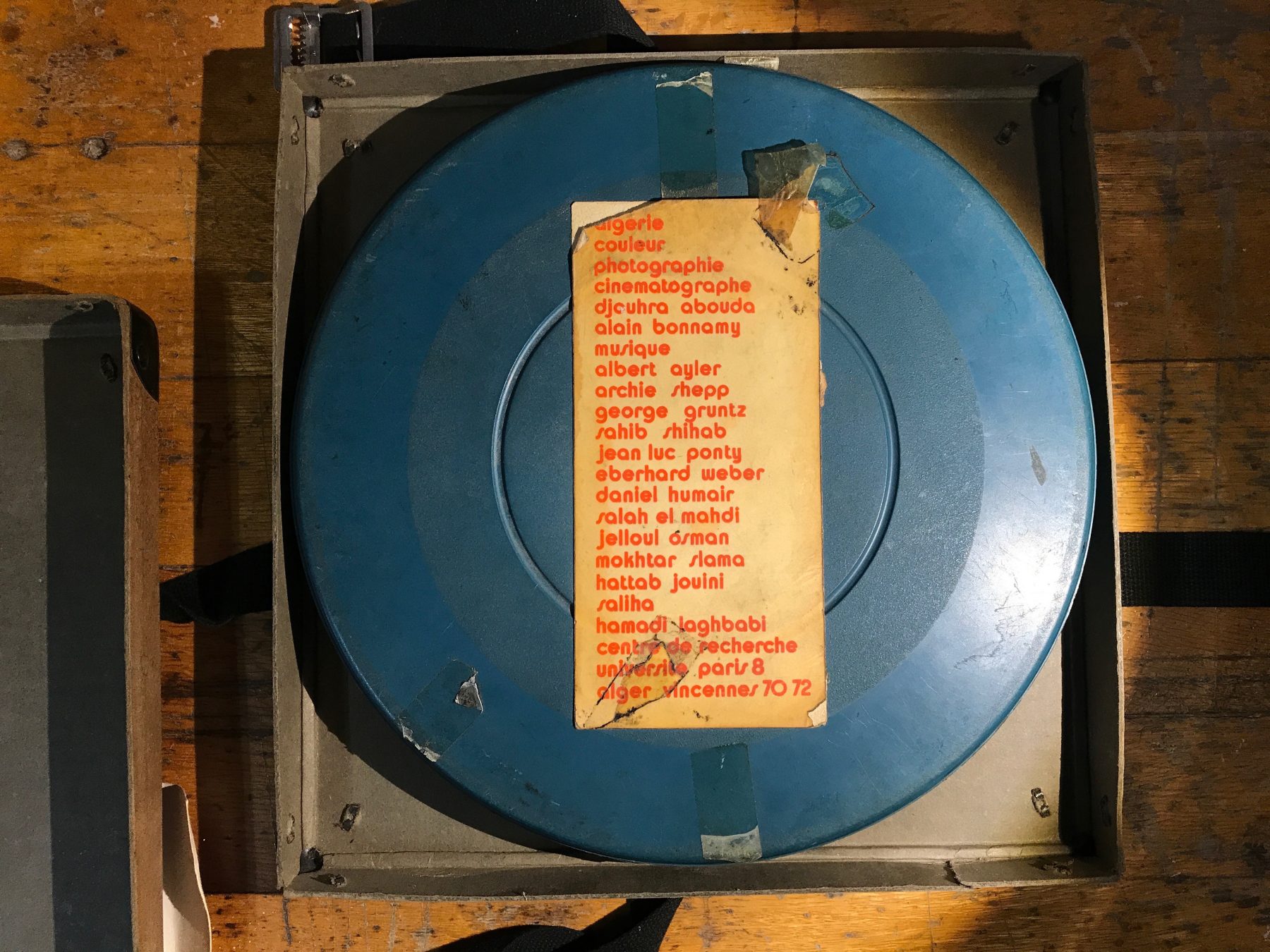

LM : It was an important question all throughout the process of restoration. Incidentally, we’ve just spoken again with Djouhra, after the latest screening, because certain dialogues, which she deems to be very important, are inaudible or only understood with difficulty (due to diction, accent, expressions used, etc.). This could seem regrettable. Some subtleties escape us. Of course we haven’t subtitled the film, in simple respect to the original oeuvre, for the objective of restoration is not to propose a more legible experience of the film, but to reconstitute as closely as possible the first intentions of the filmmakers and work itself, as it was at the moment of its creation. And Djouhra Abouda clearly indicated to me in our interviews that it was a question of a politically partisan stance, the decision to not subtitle the French of this Algerian immigrant worker. But I ask myself about another choice (all choices are made in agreement with the filmmakers, of course) – we did nevertheless subtitle the part in Arabic, as well as the song at the end in Amazigh, while in the 16 mm distribution copy that was with Alain Bonnamy, there were no subtitles for these sequences. Dhouhra didn’t remember the reasons for this, maybe budget issues, but it reminded me of the aesthetic and political positions of Med Hondo. Not subtitling entire passages.

Each step raises technical, aesthetic and political questions. The film must be reconstituted as well as its intentions, forms, and movements. Restoration, far beyond technical labor to recuperate damaged images, is this work of investigation, restitution, and recirculation of films. For this last stage, elements of communication concerning the new distribution of these “restored” films may completely smooth out or erase their history, removing all matter (in the fashion of restorations that don’t take into account the graininess of the film) and all complexity, “myth”-ifying the film or reducing it to mere affairs of censoring or even utilizing a vocabulary of discovery, as if the film were a lost treasure that had been found by pure coincidence. Whereas its descent into oblivion finds its place in systematic policies of invisibilization of non-dominant cinema. The film will be called “rare”, “unique”, “censored”, “disappeared”, “lost”, “rediscovered”, without any additional explanations. This over-utilized vocabulary participates in the erasure of the complexity of a film’s history. As if the non-existence of Mostafa Derkaoui’s film in the History of cinema was due only to policies of censorship and repression in Morocco. As if the interest garnered by the film today was due only to a purely fortuitous rediscovery of the film. When in fact its disappearance as well as it reappearance both exist in a context of domination in the political histories and the histories of form that are deemed appropriate to consider. We must be vigilant when considering this vocabulary in order to avoid reproducing patterns of domination… This, too, is restitution.

Screen shot of the digitization file of the 16 mm copy of Ballade aux sources (Med Hondo, Bernard Nantet, 1965) © Ciné-Archives

AA : I agree with you, considering that the films are rarely seen, if not forgotten, even though they were produced in France. Yes, in the case of work on the filmography of Med Hondo, the term “restitution” makes sense. It makes me think of Ballade aux sources (1965), the first film co-directed with the photographer and journalist Bernard Nantet. It’s a film that is part of Med Hondo’s filmography, but for which I have no trace of circulation. The only 16 mm film copy of this oeuvre (which was on inversible film, and so no negative) is in bad condition. For the moment, the audio tape of the film is in too poor a condition for us to be able to utilize it, or recuperate data. In the documents at my disposition, Med Hondo has communicated little about this film. However, the themes it takes on and the quality of the film offer sufficient reasons that push me towards wanting to work on its restitution. As of now, I have digitized the film, which runs 31 minutes, in several stages. The next step is to have the audio tape assessed.

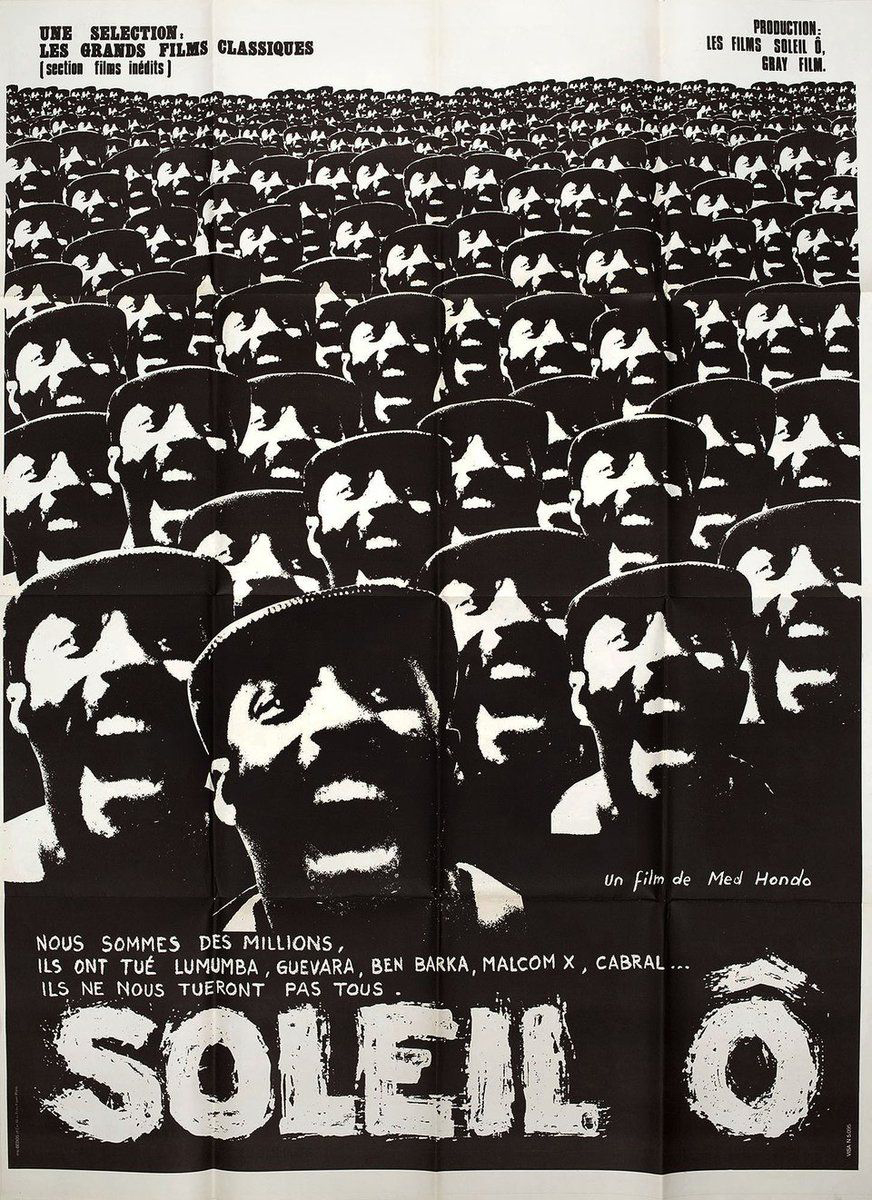

LM : And so you too, with your own tools, work on “restitutions” of Med Hondo’s films, setting them back in circulation, removing them from silence, and all this without necessarily passing through the prestigious film restoration laboratories? What I mean is that a film such as Soleil Ô benefited from a restoration program at the Cineteca di Bologna and the African Film Heritage Project (a collaboration between Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation, the FEPACI, and UNESCO). It’s magnificent, but despite the sheer immensity of the work done by their teams, it’s still insufficient. There are so many other films, short films, documentaries that are part of this history we’re trying to recover.

Screen shot of the digitization file of negative images of Polisario, a people in arms (Med Hondo, 1978) © Ciné-Archives

AA : I think that sometimes it’s possible to take a step aside, put yourself at a remove from the original inclination to digitally restore. Restoration is work that requires time, documentary research and expertise. Several stages lead subsequently to work on digitization in 2K or 4K, depending on means, and post-production in the presence of the director/s and/or cinematographer, in the best of circumstances and, at the end of this process, a return of the restored film onto analog film. All of this necessitates a substantial budget.

I digitize original 16 mm negatives using the tools available to me at Ciné-Archives. I try to make digital masters of films. In the context of a reduced economy, this is work that that allows us to have a digitized master of the film. The objective is to obtain, in the case of Polisario, un peuple en armes, which I’m currently working on, a screenable film that can be circulated and rediscovered. And yet, there’s no restoration work done on sound and image, and this must be contextualized when the film is shown because the quality and even the economy are not the same. At the end of November I’m going to be trained in grading at INA (Institut National de L’Audiovisuel). This remains a necessary professional step in the process of restoration.

Alternative models are being set up. For example, the restoration project for several of Jocelyne Saab’s films led by, among others, Mathilde Rouxel and Jinane Mrad, working with the Association of Friends of Jocelyne Saab, is stimulating. A series of workshops to train people in digital restoration of films in Lebanon and Marseille has been set up with the participation of the Beirut Cinémathèque and the Polygone Étoilé, a site for multidisciplinary creation in Marseille. The model of restoration projects for Moustapha Alassane’s Samba le Grand (1977) and Balufu Bakupa-Kanyinda’s Le Damier (1996), led by Amélie Garin-Davet for the French Embassy in the United States, opens up possibilities. A partnership set up between NYU and its department dedicated to film restoration, while the Institut Français, which manages the rights to these films, works on digitization of the films.

The restoration of films is part of the film industry. Even if this is necessary, it is also encouraging to find alternatives that link university research projects (in the case of Jocelyne Saab’s films, the desire to work with people concerned by these images) and concrete technical training. This is also what you have been developing for several years now, in Morocco in particular.

The Children of War (Jocelyne Saab, 1976) before – after digital restoration © Association Les Amis de Jocelyne Saab

LM : Yes, that was the case with About Some Meaningless Events, whose entire restoration project was conceived of as the extension of the very ideas of the film and its production, in other words in an engaged and participatory manner[3]. At the Archives Bouanani in Rabat, an apartment-film museum, transformed into an association of validation of cultural and cinematic history in Morocco, we’re working (as part of the team led by Touda Bouanani, daughter of the filmmaker Ahmed Bouanani) on the re-appropriation of Moroccan images and stories (collected by his family and beyond) by young generations and the preservation of these archives for future generations. Reactivating his archives is perhaps an attempt to restore them collectively. I think it’s essential to associate the technicians, practitioners, thinkers, and communities concerned by these images, as well as disorganizing bodies of knowledge and exploding frontiers as a way to better approach the restitution of the wish(es) of all these filmmakers, whose practices were often not limited to a single discipline. We can also mention the work conducted in an independent manner by Nabil Djedouani for 9 years now, with “The Digital Archives of Algerian Cinema”. In addition to his extremely precise research, collection, and documentation work (on line), he has just been trained in digital restoration at INA because he wanted to be able to contribute directly to this work that we have described as multiple. The films require particular sorts of knowledge and attention (this is the case with experimental cinema, militant cinema, but also of “third cinema”, as defined by the Argentinians Solanas and Getino in 1969 to describe this new decolonialized cinema[4]), and it is important that each person in this chain that constitutes the “restoration” share his/her knowledge. And it is even better when we work with partners engaged in the same struggles as those defended by the filmmakers. It was a pleasure to collaborate with the Polygone Étoilé in Marseille in particular.

________________

[3] Even though the restoration was led by the teams at the Filmoteca in Catalunya (Spain), this project was part of a years’ long research project, associating many filmmakers, artists, and intellectuals in Morocco at the Observatory (Art and Research, Casablanca), which organized several public sessions and encounters with the filmmaker, in particular in Casablanca neighborhoods, and this all throughout the process. Today the film continues to be widely shown, from Tangiers to Ouarzazate, in festivals and ciné-clubs, in particular thanks to the efforts of the critic Ahmed Boughaba.

[4] OCTAVIO GETINO et FERNANDO SOLANAS, VERS UN TROISIÈME CINÉMA, Tricontinental No. 3, 1969

Digitization of Djouhra Abouda and Alain Bonnamy’s film Algérie Couleurs at the Polygone Étoilé, Marseille, 2021 © Talitha

And so, yes, we are obliged to invent methods, especially since these restoration projects often do not respond well to established properties, those of national policies of preservation or those of the market for cinematic heritage. Even as the necessity, even the urgency, of rendering certain (non-aligned?) oeuvres visible sometimes makes itself felt. The real calls out to them, for what they open up in the thoughts and actions of the present, for what they will perhaps permit for our futures. This could be the urgency of looking at current events head on, the urgency of re-establishing forgotten histories, of establishing genealogies, to confront, to transmit methodologies of resistance, to reclaim heritages. And the film archives we’re working on have this particularity. They document invisibilized and marginalized histories, whether by their geography of production (from regions considered at the time to be peripheral) or their context of production, whether they were made in militant contexts or decolonial struggles. And we know that the patterns of domination in production, and then in narration, are reproduced at a time when policies of film restoration are in favor. The same thing applies to policies of conservation – which makes me think of the efforts of Aboubakar Sanogo (a member of the FEPACI in charge of the African Film Heritage Project), who proposes we rethink the whole apparatus of archiving, including the architecture of places of conservation. It happens to be, for example, that according to certain studies, traditional architecture, long de-legitimized by colonialism, would be more pertinent for the conservation of film. Which means reinventing and decolonializing the physical architecture of archives (and with it all associated methodologies). Here too, the physical (in this case the building structure) is political. “We come from the sun as Med Hondo said, Soleil Ô means we come from the Sun. The idea is to really capture that energy and create our own conditions for the labs. It is a whole ‘dispositif’ to use a Foucauldian term – the whole apparatus of archiving from the intellectual conceptual dimension to the physical infrastructure, exhibition and pedagogical.“ Aboubakar Sanogo [5]

________________

[5] Aboubakar Sanogo, interview by Mark Cosgrove, 2019, Archiving and restoring Africa’s film heritage: Visions and Challenges. www.watershed.co.uk/articles/archiving-and-restoring-africas-film-heritage-visions-and-challenges

poster for Soleil Ô (Med Hondo, 1970) © Ciné-Archives

________________

Translated from French by Liz Young