Kamña’s Fire, Kina’s Calling

Kamña’s Fire, Kina’s Calling [1]

One must leave the island in order to see the island[2]

It is the time of fire. And Kamña wants to expand its blaze. The fire of Kamña is gunpowder, flame and fuel for an unbound fire that scorches the earth, that drowns villages, that decimates people. Kamña’s insatiable thirst still lusts to carve out deserts. Kamña wants meat, lot’s of it, red and bloody, sacrificing hordes of sacred animals[3]. Kamña fights in name of a diabolic God who wants nothing more than to be forever God, trusting that God and “mine” are one and the same thing. Since the “first contact” [sic] with Kiña, Kamña brought along the metal smoke, the epidemic smoke[4], the smoke of the bomb-that-burns-within.[5]

Kamña’s fire has no limits, no body of its own and wants to expand its blaze even beyond the “dismembering of immense areas of land – still today under the control of a small number of families since 1534 when the Hereditary Captaincies were established”, the first method of territorial dispossession used by the Portuguese Crown to seize the lands of Pindorama[6].

________________

1.“Kamña, a term that comes from kiñayara, the language of the indigenous Waimiri-Atroari people, self-designated Kiña, who inhabit the region situated on the left bank of the lower Negro River, in the basins of the Jauaperi and Camanaú rivers and their tributaries, the Alalaú, Curiaú, Pardo and Santo Antônio do Abonari rivers in what we call today the Brazilian Amazon. Kamña is the Kiñayara term to identify the non-Indigenous, as opposed to Kiña which means the people, our people, that is, the Waimiri-Atroari people.” (source: Egydio Schwade and Wilson C. Braga Reis, 1st Report of the State Truth Commission: The Genocide of the Wamiri-Atroari People (Manaus: Amazonas Truth Committee, 2012)

2.I’m grateful to friend, artist and researcher Poliana Pieratti who cites (in her own way) José Saramago’s book Tale of the Unknown Island (Lisboa: Caminho, 1997).

3.Environmental Minister Ricardo Salles refers to the felling of the Amazon forest as an asset for “letting the herd through” in reference to the project of terraforming the Amazon forest in order to make way for monocultural, agroindustrial and livestock estate farming.

4.Reference to an expression of Davi Kopenawa: “The smoke from the machines and engines is dangerous for the inhabitants of the forest. It’s a metal smoke, a pandemic smoke. We had never smelt such a thing before the white men arrived. We are different […] we have never lived, unlike the white men, in scorched lands and without trees, with machines running everywhere.” in Bruce Albert e Davi Kopenawa, A Queda do Céu: Palavras de um Xamã Yanomami, trad. Beatriz Perrone-Moisés (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2016), 309-310.

5.In June 1985, sitting on the sidewalk in front of the FUNAI building in Brasilia, in the company of two Waimiri-Atroari, one of them asked Professor Egydio Schwade: “What is it that civilized people throw out of airplanes that burns people’s bodies from the inside? And he tried hard to explain a fact that happened in a village where many peo”ple who were friends of his family lived.” (Source: Egydio Schwade, “Why did kamña kill kiña?, blog Casa da Cultura do Urubuí, May 15, 2011. http://urubui.blogspot.com/2011/05/2000-waimiri-atroari-desaparecidos.html.)

6.Pindorama is the name of the lands of the Northeastern coast of South America, according to its inhabitants in ca. 1500: the Tupi-Guarani.

Kamña is the master of unspeakable methods of disappearance – vanishing whatever it wants: rivers, peoples, forests, animals, bodies, students, activists, macaws, pumas, children, archives, museums, communities… All that stands in its way, Kamña makes disappear. Intoxicated with its latifundary Cartesianism, Kamña is unable to understand that, in truth, nothing disappears. Everything that Kamña makes disappear, eventually reappears, uprooted or unearthed. Everything returns to haunt it.

Chorus: And who is Kamña? Kamña is a sly beast. Kamña is a beast that tames. Kamña is inHuman. Kamña is unReasoning. Kamña brings inCivilization. Kamña is gunpowder. Kamña is rifle. Kamña is highway. Kamña is white powder that falls from the sky and burns within. Kamña is arson. Kamña is fire seen from above. Kamña is napalm. Kamña is tarmac. Kamña is easy rider[7] . Kamña is maxi (bomb).[8]

Kamña is us, inhabitants of this ever-expanding desert known as modernity. Yet Kamña’s primordial mythological drama[9] is to repeatedly face two of its most significant and noble enemies: the Forest and its inhabitants.

*

breathe

*

________________

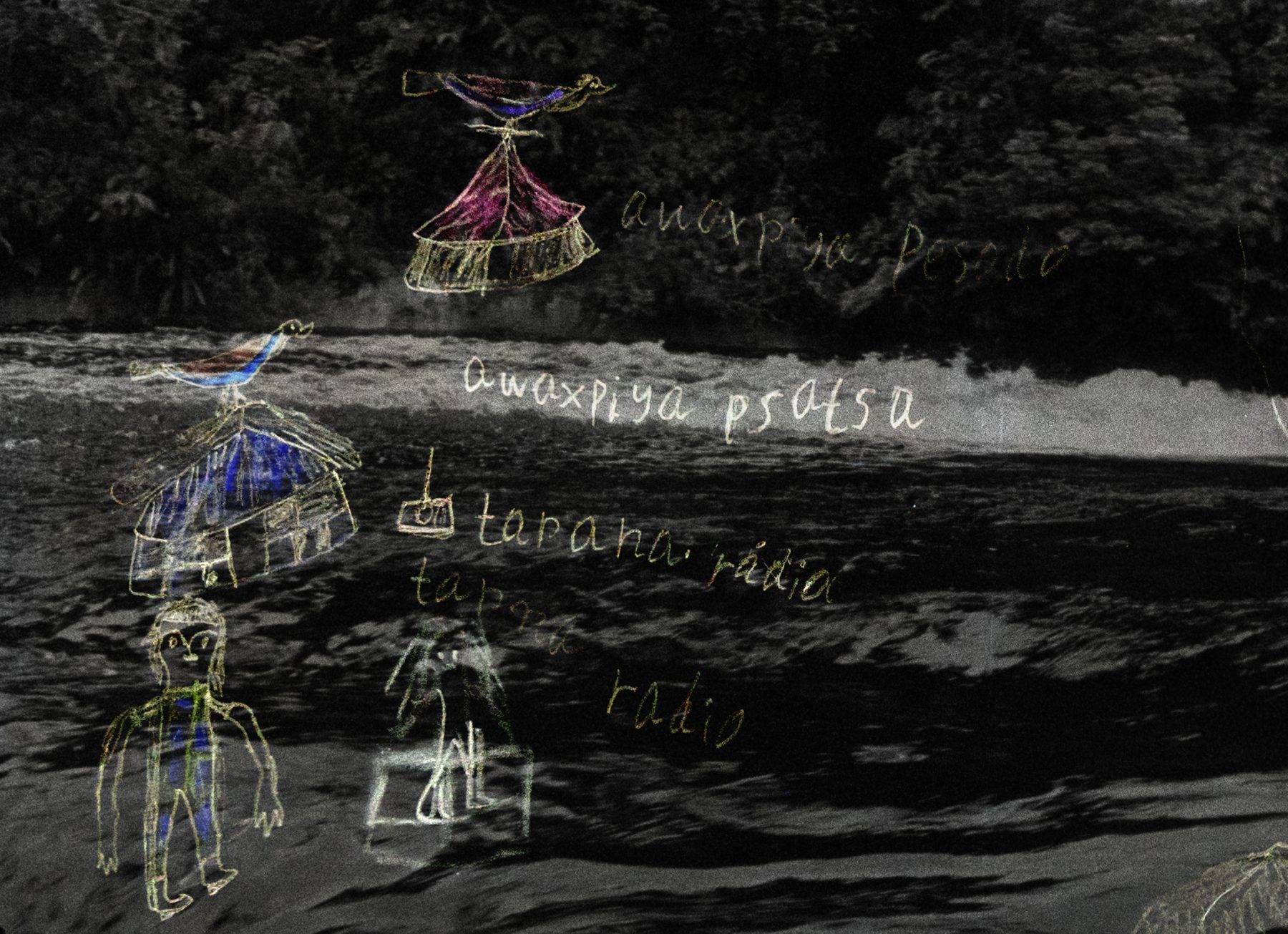

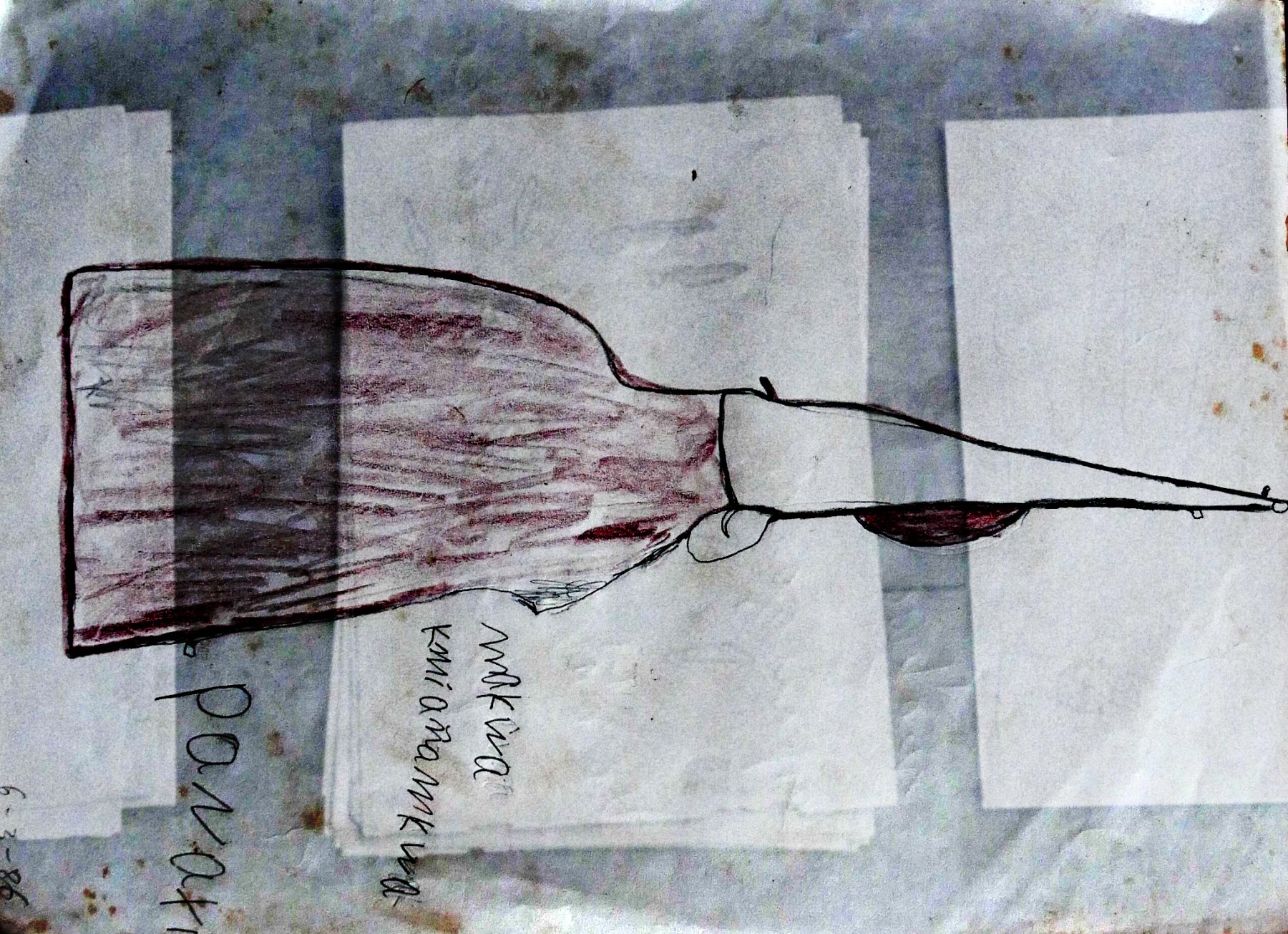

7. Benito, annotation to the Kiña drawing, Carona Fácil [Easy ride]. Escola Yawará, 1986 (Urubuí House of Culture archive).

8. Olindo Panaxi, annotation to the Kiña drawing, Homens com fuzil, bomba [maxi] e escondidos [Men with rifle, bomb [maxi] and hidden]. Escola Yawará, 25 de maio de 1986 (Urubuí House of Culture archive).

9. Kamña might well be described with one of the most complete cantos written in the life-work of my father, the composer, artist and thinker Guilherme Vaz who I re-transcribe here, allowing myself some additions: “The conservative society (of Kamña) is a mistake of the becoming of species and, simultaneously, the origin of all its mistakes. Without exception. Its capital objective is to avoid ecstasy. Knowing instinctively that it is inflexible, in nature it finds its greatest enemy. For this reason, it moves all the forces against it. As nature, by definition, has no enemies, this is its greatest audacity and its primordial mythological drama.” (Guilherme Vaz, “Três ventos, dois vácuos e uma espada [Three winds, two blanks and a sword]”. In Guilherme Vaz: uma fracção do infinito, ed. Franz Manata. Rio de Janeiro: CCBB, 2015). I would add that, everything being nature, the conservative society of Kamña emerges as something altogether supernatural.

It was the end of the dry season and the first drops of Amazonian rain were falling on the bonnet of the car. K. asks me: is there somewhere you’d like to stop and film? I reply: K, the only thing I really want to film is the (highway) BR 174, could we take a detour there? K. looks at me and laughs, you’re clearly not from around here, steps on the accelerator and says: The BR 174 is our only way there. Overwhelmed, I gulp and say: Then I’d better start filming now.

In the car, the radio broadcast comes and goes, just like the conversation with K. The rain thickens and silences all communication. The windows fog up and we can barely see ahead. The BR-174 extends over exactly 971km from Manaus to Boa Vista. The tarmac slashes, in vertiginous waves, through the Amazon jungle. It’s hard to hold the camera, each shot shudders with the road. The sound of rain overlapping the car engine is deafening. I take the microphone and place it on the bonnet.

Low clouds pass over the road, and open a glimmer of light. I take the cue to thank K. for the journey, the company and, most of all, for having managed to find Sr. Egydio. It took months of searching, trying in vain to reach him via the usual means of long-distance communication (phone calls, emails, online messages). No such luck. K. told me she only managed to find him because she grabbed the car and drove out three hours in the rain to Presidente Figueiredo[10], without a proper address, upon arrival she saw a red flag standing on a small wooden house and thought: this must the place. K. got out of the car and clapped her hands outside the house. And there he came, softly footed, at his gentle pace.

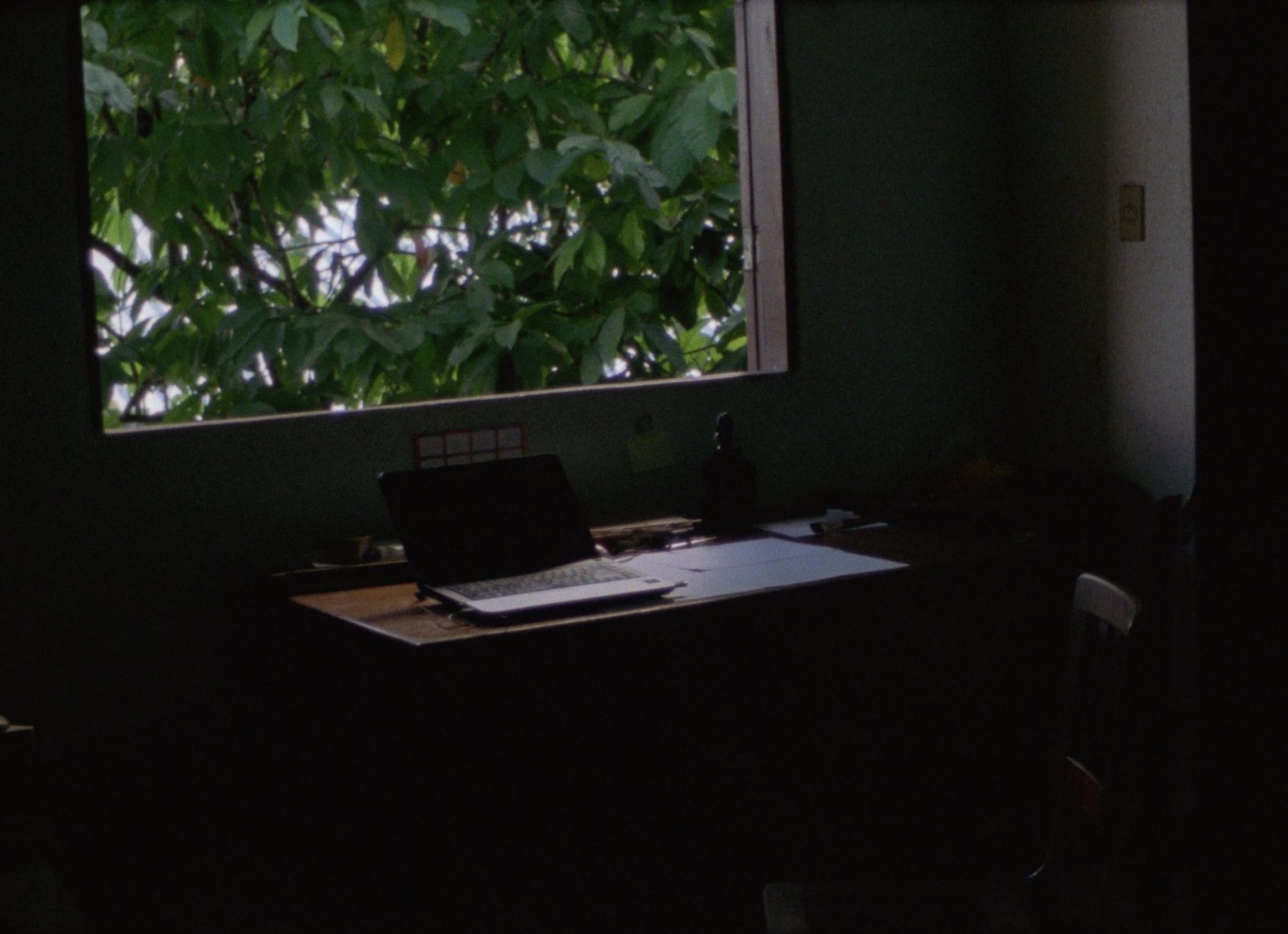

Indigenous rights militant and educator Egydio Schwade has lived for over 30 years on the margins of the BR-174. He has transformed his house into a house of culture called Urubuí, an homage to the river, that flows mightily parallel to the highway. It is in the House of Culture of Urubuí that over 3000 drawings are kept, made by the Kiña during an early experiment in bilingual literacy led by Egydio and his companion Doroti Alice Müller Schwade, in Kiñayara[11] – their mother tongue – and in Portuguese, a demand by the Kiña to defend their rights in the world-tongue of Kamña.

In the library of the House of Culture of Urubuí, books about beekeeping, permaculture, biology, critical pedagogy and Indigenous writing fill the shelves. On a nearby wall, painted green and faded by time and light, an expressive Indigenous face weeps over the BR-174, on a poster for the Movement to Support the Waimiri-Atroari Resistance.

Before we start the interview, a group of biologists from Minas Gerais arrives quietly, all dressed in white, as if in a research laboratory. Egydio and his son Maiká take them to a homespun cane chair, where extremely rare Amazon bees have made their nests. The scientists delicately open the cane with pincers and extract a miniscule yellow goo, which they deposit in a vial: eggs laid by the queen-bee.

On the balcony of the small wooden house, Egydio’s hands pull images from a small photo album: Here’s Doroti with our sons next to the Yawará school, they attended the school like almost all the residents of the village. Women, men, children and even babies participated. An indigenous child smiles in the foreground, behind her, two extremely fair children also smile next to a group of Indigenous children and women. In the middle of a forest trail, a group of Indigenous men, laughing, point their arrows towards Egydio’s camera. Here are the boys from the village playing with their bows and arrows during a walk. Kiña’s arrows pointed towards Kamña’s camera-eye. Here, a different Kamña, bringing not gunpowder, fire or weaponry, but coloured pencils, open ears, and sheets of paper.

________________

10. Ironically, the name of the city is an homage to the military ex-presidente João Figueiredo, despite his having rejected it after his inauguration in 1981.

11. The literacy praxis in Kiñayara meant the educators learnt the Kiñayara language and co-created a spelling standard for the Kiña language, until then an entirely oral language.

Egydio and Doroti Schwade were sent by the FUNAI (National Indigenous Foundation) to the Yawará village of the Waimiri-Atroari in 1985 to conduct with them a first literacy project, while helping repair the damaged reputation of public institutions in the region[12]. “After the success of the diretas já [Direct elections now] campaign[13], the winds of change were about. Everyone was dreaming of a new direction for official Indigenous policies”[14] writes Egydio Schwade, recalling their lived experience with the Kiña.

Arriving at Yawará, Egydio and Doroti brought with them years of experience in the struggle for Indigenous rights in the region, as well as Tact, Time and Listening. Inspired by Brazilian educator and thinker Paulo Freire in his already celebrated and fundamental Pedagogy of the Oppressed[15], the educators put in place first and foremost a common space for attentive exchanges with the community at Yawará, through a daily practice of drawing.

Paulo Freire’s method adopted by us placed the entire literacy process as well as the production of materials in the hands of Kiña. They produced the exercises on a daily basis, far from our eyes, in the village. Each following day, these were complemented and enriched by conversations and corrections in the classroom. Through this process, a sincere reciprocity was created, even though we did not yet understand each other in Kiñayara.

An indigenous girl wrote next to her drawing: “My mother did not teach me how to make a hammock”. The message, written telegraphically, was decoded in class: her mother had died of measles very young, after her father had been killed in the resistance struggle[16].

________________

12. Since the end of the 1960s, the various clashes with the Waimiri-Atroari people had already been the subject of public criticism directed at the regional government’s actions.

13. A civil movement demanding direct presidential elections in Brazil between 1983 and 1984, offering the first signs of a future transition from the military regime in Brazil.

14. Egydio Schwade, Política Indigenista Oficial e Tentativa de Mudança, agosto 2020 (unpublished essay, sent by email).

15. Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy is described extensively in his emblematic work the Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1.ª translation into English in 1970, translated by Myra Ramos). The essentially decolonial method that Freire defends is based on the principles of collective learning with co-elaborations between professors and pupils, not as “receptacles of knowledge” but as active contributors in the making of a collective knowledge. Freire’s educational philosophy was used, commented on and activated by various independence movements, from indigenous rights to civil rights militants in the Americas, Africa and beyond.

16. Egydio Schwade, Política Indigenista Oficial e Tentativa de Mudança, August 2020 (unpublished essay, sent by email).

Paulo Freire’s philosophy adopted by Egydio and Doroti, could not anticipate Kina’s expression of the historical traumas they had experienced. The method became mostly a device for creating the conditions for exchanges to take place, by way of horizontality and improvisation, gradually eliciting the possibility to speak and be heard. The creation of this space “without fear of freedom”, is the essence of Paulo Freire’s pedagogy, one in which education is seen first and foremost as a “practice of freedom”[17]. In his own words:

genuine education is not made from A to B, nor from A over B, but rather from A with B, each mediated by the world. A world that overwhelms and challenges them respectively, producing visions or points of view about each other. Visions impregnated with anxieties and doubts, with hopes or hopelessness that entail significant concerns[18].

It is within this context that the drawings made by Kiña emerge as subjective, as much as objective expressions of their experiences and world as well as, unexpectedly, as a radical portrait of Kamña.

“What did Kamña throw from the airplane that killed Kiña? Kamña threw kawuni (from above, from an airplane), like a powder that burnt the throat and soon Kiña died.” With great caution, we sought from the start to hide our curiosity in relation to these questions. We knew we were under constant surveillance from those conspiring to cover up the crimes.

Searching the National Archives, I come across a series of documents from the SNI (Serviço Nacional de Informação, National Security Services) listing the names of Egydio and other anthropologists and indigenous militants like Darcy Ribeiro as participants in the Indigenist Pastoral meetings constantly surveilled by undercover agents . Egydio looked over the documents and breathed, unsurprised and untroubled.

“What did Kamña throw from the airplane that killed Kiña? Kamña threw kawuni (from above, from an airplane), like a powder that burnt the throat and soon Kiña died.” With great caution, we sought from the start to hide our curiosity in relation to these questions. We knew we were under constant surveillance from those conspiring to cover up the crimes[19].

Searching the National Archives, I come across a series of documents from the SNI (Serviço Nacional de Informação, National Security Services)[20] listing the names of Egydio and other anthropologists and indigenous militants like Darcy Ribeiro as participants in the Indigenist Pastoral meetings constantly surveilled by undercover agents[21]. Egydio looked over the documents and breathed, unsurprised and untroubled.

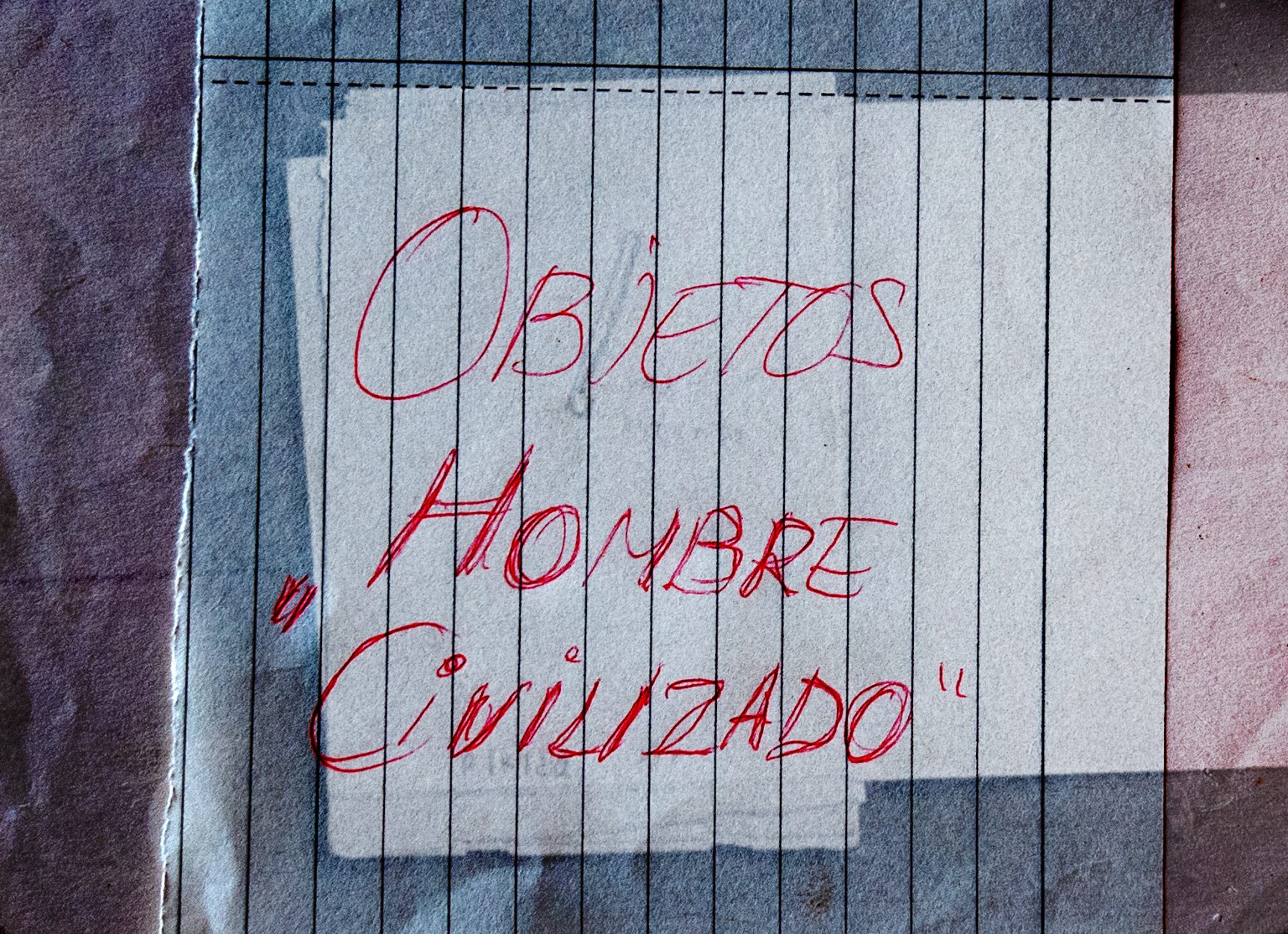

Following Paulo Freire’s method, the literacy process was conducted with the autonomy of Kiña. They began with drawings, which they mastered brilliantly. From the drawings they extracted letters, and from the letters, phrases and finally small texts, in their mother tongue. The exercises were carried out in the village. At school, they were displayed publicly, commented on, and enriched in viva voce. From this process, all the richness of their territory emerged: animals and plants, their vision of the world and how everything was celebrated in their festivities and rituals. Their history, of course, also came up – Kiñayka = the History of our people. Practically all of them were youth or children, all survivors of very recent massacres. And so they began to reveal what the military had done to their people, during the construction of the highway BR-174, tearing up their territory. And, at the end of the class, almost always the same question: “Why did Kamña = “the civilised” kill Kiña = our people? Apiyemiyekî?” = Why?.[22].

Next to a Kiña drawing, drawn with strong lines in black, leaf-green and sky-blue, we can see two malokas (indigenous houses), two red-skinned men and two hoes in purple and black, accompanied by the following annotation:

Tikiryia[23] disappeared

Kamña arrived

Taboka[24] arrived

Tikiryia disappeared

Why?

*

breathe

*

________________

17. Paulo Freire, A Pedagogia do Oprimido (Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1987).

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid

20. A State outfit created following the 1964 coup d’etat to survey and punish civil society, copying the North American CIA model

21. I’m grateful to the researcher and curator Ana Pato for her considerate sharing of these documents

22. Egydio Schwade, Política Indigenista Oficial e Tentativa de Mudança, agosto 2020 (unpublished essay sent by mail)

23. “On the left bank (of the Camanaú River), southeast of the Criminosa Waterfall (Urtanuna in the Kiña language), where the mining company Mineradora Taboca (belonging to the Paranapanema business group) is located today, at least nine indigenous villages have disappeared, according to a study by Father Calleri, in October 7, 1968, during FUNAI (Fundação Nacional do Índio / National Indigenous Foundation) flyovers. These groups were known to the Kiña as Tikiriya. ” (Source: Egydio Schwade, Wilson C. Braga Reis, 1st Report of the State Commission of Truth: The Genocide of the Wamiri-Atroari People (Manaus: Amazon Truth Committee, 2012), 12.

24. Taboka or Mineração Taboca S.A., a company “that rakes the soil of the Waimiri-Atroari to extract cassiterite, the main source of tin, a mineral used in the manufacturing of food cans”. The company has been operating in the region since 1978, extracting not only cassiterite but also tin, niobium and tantalum. (Sources: Ana Paula Rocha, The Great Wall between Kamña and Kiña, blog Plurais. Https://blogplurais.wordpress.com/2017/10/20/o-grande-muro-entre-kamna-e-kina/, last access 4 November 2020. And the report on Mining in Indigenous Lands in the Brazilian Amazon 2013 (São Paulo: ISA Instituto Socio Ambiental, 2013) 19, 31, 37.

During my 57 years of militancy for indigenous rights, this was the question that most silenced the depths of my heart, writes Egydio, in an email following our interview. Kiña’s drawings and their questions became a channel of communication, if not of therapy, about the violence of Kamña. Through gestures, words and silences, Kamña’s violent genocidal methods were articulated throughout the literacy experience.

In 1986, less than a year after this experimental pedagogical project had begun, Egydio and Doroti Schwade were expelled from the Yawará village.

At dusk on the 4th December, 1986, I had just spread over a hundred drawings of animals made at the school, all over the floor and table of our little house. We were surrounded by most of the village: boys and girls who would choose the drawings for the first book to be published by the Kiña. It was then that the FUNAI car pulled in. It was the person in charge of the Waimiri-Atroari reservation, coming to order our expulsion. We only had enough time to hurriedly gather our things and board the car. It was already getting dark. When I bid farewell to the Tuxaua[25], crestfallen and sad, all he said was: “Egydio, you, Doroti and CIMI, weak just like us!”[26]

As we reached the end of Egydio’s steadfast and quivering account, the dogs were barking and lunch was ready to be served. The account asked for silence. K. looked at me and said with her eyes: I think now it is time to breathe, let’s leave Sr. Egydio to rest. Yes, of course.

K. and I went to get a coffee and tapioca on the edges of the city, on the banks of the Urubuí river. Absorbed by the intensity and speed of the river, silence settled between us. Nothing was stronger than these waters, the low reverberations of their flow. No alphabet, all is language.

*

Kiña’s Calling

menyayakî henya? henya kepate

‘Do you see?’ ‘I see it!’

‘piapiakepa!’ – ampakepa yainîpî’

‘Do you see this?’ – said another parent of his.[27]

In the late afternoon, K. and I took the drawings out onto the veranda, light was needed in order to see the drawings. I tried multiple times, without luck, to pull focus on each of the sheets of paper. The photographed images seemed infinitely distant from the haptic reality of those drawings: pale pink in relief, almost tearing the macaw-blue, graphite powder, embossed alligator. Each stroke almost traversing the sheets of paper, such was the force, the intensity of the pencil against the image’s skin[28] — braille with no alphabet.

Kiña seemed to irrupt through the sheets of paper. Seeing, or rather touching those drawings seemed to be a way of seeing oneself through the eyes of another: watches, roads, cars, trucks, knives, machetes, radios: Kamña’s alphabet is spelled.

Now, Kiña’s drawings looked back at us. More than anything, they irrupted from the page towards touch. To see them really meant to touch them. Or, in the words of Didi-Huberman, “ultimately, seeing is only thought and experienced through touch”.[30]

Signatures of all things I am here to read, seaspawn and seawrack, the nearing tide, that rusty boot. Snotgreen, bluesilver, rust: coloured signs. Limits of the diaphane. But he adds: in bodies. […] If you can put your five fingers through it, it is a gate, if not a door. Shut your eyes and see.

If the drawings can now finally look back at us, touch us, it is because we have at last understood that what they narrate can not be expressed by sight alone. If Kamña’s fire is the fire of light that desires to see everything, reveal everything, Kiña’s subversion is a game of mirrors: I hold the pencil-mirror to paint your portrait, Kamña. What we see looks back at us.

*

________________

25. Kiña name to denote village leaders

26. Egydio Schwade, Política Indigenista Oficial e Tentativa de Mudança, August 2020 (unpublished essay, sent by email).

27. A fragment from the“myth of the alligator” transcribed by Egydio Schwade based on the description of a drawing made by one of the students at the Yawará School (1985/86). A recollection sent by email.

28. From Davi Kopenawa speaking to anthropologist Bruce Albert in reference to the printing of words in books, literally dead trees: “You drew these words and stuck them on paper skins, as I asked you to. They went far away from me. Now I would like them to divide themselves and propagate over long distances so they can truly be heard […] Unlike them (the whites), I do not possess old books in which my ancestors’ words have been drawn. The xapiri’s words are set in my thought, in the deepest part of me […] these words will never disappear. They will always remain in our thought, even if the white people throw away the paper skins of this book in which they are drawn […] They can neither be watered down nor burned. They will not get old like those that stay stuck to image skins made from dead trees.” in Bruce Albert and Davi Kopenawa, The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman, trad. Beatriz Perrone-Moisés (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2016), 64-66.

29. I’m grateful for the lucidity of researcher, writer and filmmaker Raquel Schefer who, in her essay on “Apiyemiyekî?” (published in the Black Canvas Festival, México catalogue), describes this dimension of a mutuality of perspectives in the encounter with these drawings. This reflection immediately summons to mind Georges Didi-Huberman’s precious book Ce que nous voyons, ce que nous regarde (no english translation)— a critical philosophy, if not a perpectivist one, of seeing.

30. Georges Didi-Huberman, O que nós vemos, o que nos olha, trad. Golgona Anghel e João Pedro Cachoppo (Porto: Dafne Editora, 2011), (my translation)

post script

A year after visiting the House of Culture of Urubuí, I was invited to talk about the research and making of Apiyemiyekî? (2019) as part of a virtual conference about archives, memory and subjectivity with a group of women researchers from PUC-RJ (The Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro). Four hours’ time difference separated us, though our respective computer screens gave us the illusion of being together in a small and engaged gathering. frutapao (the group admin) lets us know: we’re going to watch a few minutes of the film and then we’ll come back here to discuss it.

Opening scene: the winding highway BR-174 in black and white, filmed with a shaky camera, from within a car. K.’s voice irrupts from the image: Hi Ana, I wanted to say… I don’t know if your research goes beyond 1985 or not (the year marking the end of the military dictatorship in Brazil) but if it does, I think Egydio might have more to say about what happened and the consequences of it… Because it’s as if the dictatorship never ended for the Indigenous, and they are still at the receiving end of all this violence, this violent charge . At this exact moment a number of unknown profiles invade the group, with the following images: a young man films himself whilst a woman (who we can’t see) performs felatio out of frame, a young half-naked woman performs a choreography for the camera, two men humiliate another stretched out on the floor, pretending to “search him” and finally nazi parades, rifles, machine guns, pleasure-less pornographies and electoral slogans in green-and-yellow, whilst in the chat the same phrase is repeated over and over again: where is the man in this !@#$%& conversation? Accompanying the images, a deafening cacophony of sounds silenced any possibility of communication. Staggered as we were, it was impossible to carry on.

We reconnected later, groping for a way to describe, to find a name for what had happened. Trembling with words, a different alphabet was born. Stammering, unformed, delirious. In my notebook, I find these cryptographies ripped against the paper skin: resistance, struggle to keep on living, against the appropriation of life, body memory, the historical force of the river, delirium, haunting, river that invades the highway, a perfect uchronia.

After the cyber attack, I went out with a friend to talk. It was the end of the day and the sun was setting, enormous, knowing, whole. When I told him what had happened, he stopped and thought a moment and then said: but wouldn’t it be you – researchers of memory and the senses – who are the real hackers of Kamña’s latifundium? [31]

*

* *

________________

31. With thanks to friend filmmaker Ben Russel for this omen.

This essay was a commission for the project Terra Batida (edited by Rita Natálio, Margarida Mendes, Marta Mestre) a network joining artists and researchers around social-environmental conflicts in the Portuguese territory and beyond.

bibliography

Albert, Bruce e Davi Kopenawa, A Queda do Céu: Palavras de um Xamã Yanomami, trad. Beatriz Perrone-Moisés (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2016).

Kucinski, Bernardo, K.: Relato de uma Busca (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2016).

Didi-Huberman, Georges, O que nós vemos, o que nos olha, trad. Golgona Anghel e João Pedro Cachoppo (Porto: Dafne Editora, 2011), 11.

Freire, Paulo, A Pedagogia do Oprimido (Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1987).

Rocha, Ana Paula, O Grande Muro entre Kamña e Kiña, blog Plurais. 20 outubro 2017. https://blogplurais.wordpress.com/2017/10/20/o-grande-muro-entre-kamna-e-kina/.

Schwade, Egydio e Wilson C. Braga Reis, 1.º Relatório da Comissão Estadual da Verdade: O Genocídio do Povo Wamiri-Atroari (Manaus: Comitê da Verdade do Amazonas, 2012).

Schwade, Egydio, Política Indigenista Oficial e Tentativa de Mudança, agosto 2020.

Valente, Rubens, Os Fuzis e as Flechas: Histórias de Sangue e Resistência na Ditadura (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2017).

Vaz, Guilherme, “Três ventos, dois vácuos e uma espada”, in Guilherme Vaz: uma fracção do infinito, ed. Franz Manata (Rio de Janeiro: CCBB, 2015).

credits

Essay based on the research and making of the film Apiyemiyekî? (Ana Vaz, 29min, 2019).

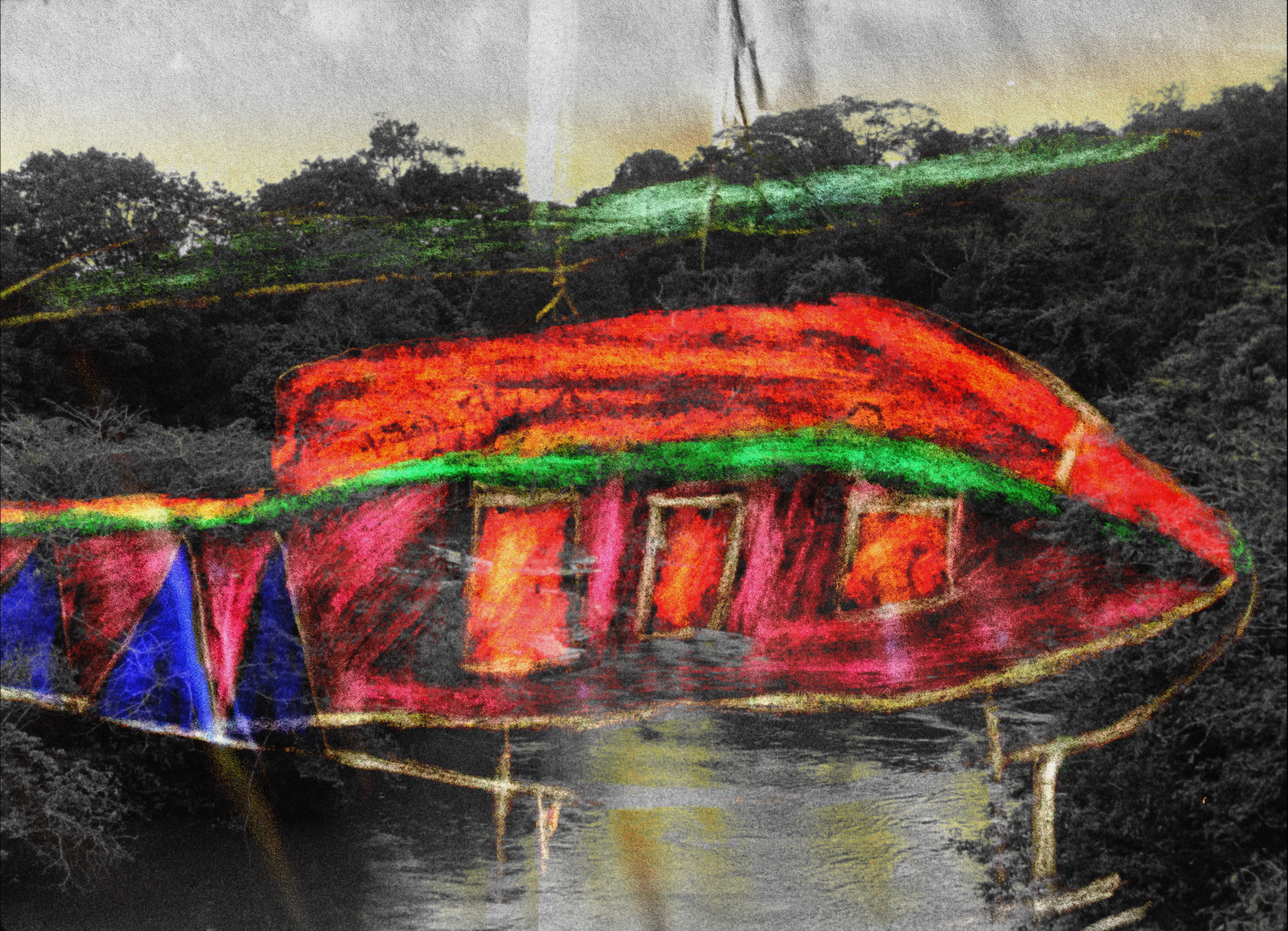

Image credits: Ana Vaz, Apiyemiyekî?, 2019. Fotograma 16mm transferido para HD, 29min.

Thanks: Grupo Lacuna Aberta (PUC RJ), Poliana Pierati, Ana Pato, Egydio Schwade, Ben Russell, Catarina Boieiro, Keila Serruya.