Conversation Piece

July 23rd, 10:01

Dear Olivier, I’ve been gathering thoughts and forms to start over a conversation we began back in 2018 under the spell and the title: Parler l’Ombre — as in to speak shadow, more than to speak from the shadows. It is significant that we chose to take out the proposition and move directly to the noun, towards the shadow rather than its representation. Particularly in regards to cinema, a cinema of the shadows would be one that rejects the tyranny of light and embraces the imprecise borders of the shadows as an accomplice. More than a conversation, Parler l’ombre has become a way of being and making. Here is an extract:

If we consider cinema to be an art of sight, an art dependent on light, then a cinema that refutes the Lights (and its “Enlightenment”), must reconsider what the cinematic machine is capable of doing beyond casting of light as the privileged form of representation. Unlike what is traditionally believed, I like to think that cinema is not only an art of sight but rather that other dimensions of our sensorial apparatus are in motion alongside its engines. Experimental cinema, frequently cast in the role of misfit to so-called narrative cinema, has historically explored the medium’s shady margins and transformative strength in re-shaping our relationships with space and time as well as with the bodies that we co-inhabit these dimensions with.

I would like to take Starhawk’s Dreaming the Darkas a means to consider what Filming (in) the Dark may be. Starhawk’s Dark[1] can be taken as the nebulous matter that puts us at risk, that has no form (yet), no identity, nor shape – all that was rejected by the Modernity of Light. The Dark is not a space nor a figure, neither an ideal nor ideology, it lives in secret and is whispered only in specific conditions, by specific bodies, in situations that elicit and confirm the spiritual dimension of being. It cannot be everywhere as it is always dependent on a somewhere. And it seems that it is precisely this dimension of the “nebulous matter that puts us at risk” that troubles the order of those who trust the Light. I would go so far as to say that it is precisely the fear of risk, inherent to being alive, that has risen the prison walls of modern life.

We could think of the colonial massacres in the Americas or even the witch hunts in Europe as crusades against those who reject the Light, who reject the extermination of risk, who are not reigned from above, but rather from below, whose land does not belong to them but rather who belong to the land.So for me the idea of filming (in) the dark entails a rejection of the all seeing eye who sees from above, who grants meaning and names, rather it knows that a camera is a perspective and hence a body that can only see partially and is traversed by what it films because it is there. And because this translation of being there is so difficult and imprecise, there is always a cryptic dimension to the films, as they cannot make explicit something that is as subtle, tactile and situated as being in the presence of.

To film (in) the dark or mettre en récit l’ombre would beg us to untame our sight in conjunction with our other senses, our capacities to see and to sense, to prolong the experience of presence or, in the words of Rosi Braidotti, to “rethink the corporeal roots of human intelligence”[2].

Three years have passed since we wrote Parler l’Ombre as a conversation. Yet, a great part of me is still there. Trying to sense, to be attentive to rather than merely seeing. The nebulae of the present hour is thick. It is July 2021, the year already forecast to be the second greatest on record for carbon emissions. Wildfires ignite everywhere. Torrential rains flood even the quietest cities in the European fortress. Thousands of swimming bodies risk their lives coming to the shores of this very fortress. Meanwhile, a global disease, as viral as the system it attacks, kills and sickens thousands of human bodies every day. And yet the only common dream seems to be immunity, nothing else. On the radio, the national health service asks for “people to avoid risky situations and be aware of risky behavior around them”. The most direct translation of any sci-fi novel describing an authoritarian planet that transforms people into police agents. Again, the fear of risk, raising the prison walls of modern life.

After speaking with you today about The Living Journal I noted: Western systems of representation have alienated us, separated us from the body and hence from the earth. A return to the body is a return to the earth. My father, Guilherme Vaz, whose music and thinking you know so well by now from my films and our conversations, used to say that the West has not yet encountered what it calls Art. Rather, it avoids it constantly. I think the true manifestations of we call Art exist in the vibration of the living, beyond any representation.

tbc,

ana

________________

1.Starhawk’s Dreaming the Dark: Magic, Sex ¶ Politics (Boston: Beacon Press, 1982) is a political treatise based on collective and individual practices that entrust the spiritual as a fundamental element to political thinking. Searching to undo forms of political oppression through “Power-Over” relationships, Starhawk situates a feminist and abolitionist philosophy in which thinking and making are equivalents — a philosophy woven from within circles of collective rites as tools for emancipation.

2.Rosi Bradiotti, Patterns of Dissonance. A Study of Women in Contemporary Philosophy (New York: Routledge, 1991), p. 219 as quoted by Silvia Federeci in The Witch and the Caliban (New York: Autonomedia, 2014), p. 15.

August 2nd, 8:30

Hello Ana. I’m getting back to work again after a few days dealing with the side effects of my vaccine. Last night I wrote poetry until very late. It’s the only form of writing I do at night. I think it corresponds to that very particular moment of semi-consciousness, of letting go, that suits me. In the very difficult times we’re experiencing, it’s a form that has naturally come back to/in me, to move beyond frustration and also as a way to do something with anger. Poetry is a cinematic gesture that is both very simple and radical. It allows you to create worlds with an economy of means and to work with rhythm, montage, energy. It offers powers through bareness. For me it is an act that is not separate from my theoretical work, where I’m always trying to find a way to speak by inventing at the same time a personal way of speaking. When you write in French, as I do, there is a sort of necessity to introduce a certain speed into the text as a way to explode the meaning, the weight of the language, and to produce sensations by means of accidents, musical and chromatic collisions. Because without them, French aims for a much too specific precision in which we clearly feel a structure of violence and power, where naming participates in an epistemology of capture – in the past I’ve explored the act of naming as an act of colonial possession, by starting with my family name which, as for most of the descendants of slaves in the Caribbean, is a name written by an owner over an African name and is thereby a naming destructive to kinship and descent – naming as production of forgetting, as traffic of other possible Histories. Additionally, the French expect others to speak their language well and have an enormous difficulty understanding when it is spoken with an accent, for example. I would say that when one speaks a French that is not from France, not anchored in the territory, the very soil in fact – which is a rather common phenomenon for languages that have accompanied the expansion of large modern empires. Most of my foreign friends take this relation the French have with their language as a form of snobbery and idiotic pretension. This is not necessarily wrong, but it may be a bit more than that. I think that French is also a language conceived of as a moving fortress, a very solid architecture. It is a sort of well-guarded institution and is thus necessarily difficult to inhabit; the language knows only how to impose itself on speakers. I link this relation to language with the French universalist obsession that leads to the idea that whoever is not from here (France) must integrate him/herself; in other words, to adapt oneself to the architecture rather that inhabiting it actively, or allowing oneself to produce it towards the self and for the self. I think that through poetry I sometimes manage to experiment with a way of inhabiting this aggressive and pretentious architecture, to deconstruct it, to chip away at it and thus reach a liveable space. I dream of being able to create a poetic theory that is based not just on ideas, but also on rhythmic forms of language that can bear personal witness to this fight with and in the French Empire of the mouth and the hand. A theory that allows us to feel what the experiences of certain forms of life – that of the working classes, or of the exile in particular – do to language. But one that also produces a place of hospitality and play, in other words a space that allows for distance, movement, and breath. To reach this, one has to make oneself a foreigner to the language. And it is for this reason that “non-hexagonal”[3] French-speaking communities (European, African, Caribbean, for example) are essential to ensure that the language leads to other inhabitable places. This is what Achille Mbembé and Alain Mabanckou call “abolishing the frontiers of French”[4].

This relation to the French language of non-hexagonal communities has nothing to do with colonial injunctions and violence. It is what I call an emancipatory Relation – because I believe we must always specify the dynamic of a relation. And in this instance the clearest marker of this emancipation is the development of a form of autonomy. This shows, if it is necessary – and I believe it is – that autonomy is not opposed to the Relation, but rather and on the contrary, constitutes one of the conditions of rupture with the practices of a relation of innocence and privilege. And so I would like to find a way to verbalize a theory that could nestle precisely in the act of forming words with other words, a language within a language, in the breakdown of the sentence, the splintering of syllables, the hybridization of words and images, a language of presence. This is what Creole is – a visual language, a language of the experience of urgency that enormously condenses meaning into expressions that function as accumulations of furtive images. A language that moves swiftly, but by insisting, repeating, de-speaking and re-speaking, again and again permits the trace of a forgotten knowledge to rise up, like an accumulation of sediments and allows the form to appear without our ever being able to distinguish the moment when meaning is unveiled. Because it is never revealed at a precise moment; it is born of the entanglement of voices and frequencies. For me, this fragmentary and choral language is a tool for collective emancipation because it is always in a state of expectation, demanding a community. It has no proprietary, incomplete narrator. And so it turns its back on the romantic and heroic image of the solitary author and demiurge by opposing radical necessities and contingencies. This way of speaking in the collective cacophony – and the collisions of plurilinguistics – is a way of hiding meaning and of allowing it to come, to resurface through the (inter)play of successive readings and different repetitions. I write most often while listening to loops of music that are very repetitive but which incrementally are modified and become spirals. It is through this speed and this repetition that moves that I try to “break the language”.

If I digress a bit around the idea of language it’s because I have the feeling that it is playing a character and this character, this Body of reference, as in colonial universalism, is never clearly named. But it nevertheless applies an invisible law on our imaginations. I don’t want to enter into language the way one enters the room of the white Master. I break a window and escape with the rumour of French in the night. This is the place of language that I want to inhabit. This less travelled road is another way of evoking the forms of irreverence we’ve already spoken of and their importance as possible refusals of consent, engagements towards the living.

________________

3.In the french oversea territories, the “french european” territory is called “the Hexagon”

4.Achille Mbembé & Alain Mabanckou, Playdoyer pour une Langue-Monde : abolir les frontières du français in La Revue du Crieur, juin 2018, p 61-67, Editions Médiapart-La Découverte, Paris.

16th August, 10:02

Olivier, a few weeks have passed since our last correspondence. I have tried over and over again to begin writing back to you until I realised that after so many years of being in a kind of exile from my mother tongue, it is becoming increasingly difficult for me to express myself in any other language rather than the one that was transmitted to me as mother and tongue. The one which was passed on to me already deformed by several waves of rupture and transformation of the imposed colonial languages in the Americas, or more precisely in the lands of Pindorama[5], which we still sadly call Brazil.

You speak of French as a fortress language, but I would say that the whole of Europe and all its languages are immense fortresses defended and erected by the imposition of its Invasion Idioms. Giant walls enclosing Europe’s History as if this History had not actually been written everywhere but here. A people who look too much into themselves and fear the other, their constituent other. Constantly quoting their authors, commenting on their battles and invasions, disputing whether something is said this way or another, decorating their cities in ode to assassins.

I have never been able to understand the meaning of the daily fights in which people face each other to defend their language: “this is not how we say this”, “here we speak this way”, “this has to be pronounced that way”, etc., etc. Where I come from Invasion Language is made and remade daily with might and invention. When something otherworldly is pronounced, it is a cause for celebration. This is how new linguistic expressions are invented every day, deformed arrangements to escape the tyranny of Invasion Language. We, in the Americas, have been forced to look at Europe with reverence, but the reality is that this is not natural for us. Irreverence is perhaps the greatest characteristic of Pindorama.

You say you don’t want to enter a language as one enters a White Master’s house, but I tend to think that no one wants to enter any language under the law of the Casa Grande[6] (Master’s House). This is why languages are not invented in palaces. A language is invented by speaking, by feeling the rhythm of a tongue with the tongue, the music of the words in the body, the resonance of sentences on the feet. A language is perhaps innately geographic as it is also made of winds, rivers and highways accelerating or delaying the curve of the tongue. We learn to speak a language the way we learn to step the ground. This is where it begins: on the foot rather than the hands. A language is to be danced with feet and heaps, not marched[7] with stumps upon the earth. Yet, language will always be in delay in regard to the rhythm of life. And this is its greatest quality: delay and imprecision.

________________

5.Pindorama is the Tupi Guarani name for the lands on the southeastern shores of South America.

6.Casa Grande was the designation of the colonel’s headquarters in sugar cane slave labour plantations in colonial Brazil.

7.I thank friend and colleague Ephraim Asili for this great analogy of how in Europe dancers tend “to march” to techno music rather than curve around the innate and subtle polyrhythms of the original Detroit beats.

18th of August, 10:00

A poem precisely, from this world that does not want us.

Whatever

The matter

Of the sky

Whatever

The thickness

Of the ghost

Glide

The night

Doesn’t want

Us

You could say

That it’s

Bad luck

Life

Empties

And looks itself

In the eye

Naked

Glide

The night

Whatever

The texture

Of the light

And the years

And the stars

Whatever

The expansion

Of the universe

Doesn’t want

Us

So

Whatever

The fire

Between your hands

Petroleum

Burning

Underneath

The gaze

Treasure

Yellowed

By acid

Whatever

The mineral

Blue

And the explosions

Underground

The Earth

Doesn’t want

Us

Whatever

The depth

Of the abyss

The fish

Whose bones

Are bared

Shine

Even more

Than our

Old artificial

Stars

And the elastic

Mass

Of the ocean

Doesn’t want

Us

So plunge

Into the heart

Of the fire

Pray then

To the unnamed

Planet

The wild

Sun

And the wayward

Particle

Pray then

To the magnetic

And ageless storm

Doesn’t want

Us

Doesn’t want

Us

Whatever

The paleness

Of the living

The transmissions

Of the eye

Never

Dry of lithium

On the surface

Of fluorescent

Pools

Sulphur

Devours

Oxygen

And the air

Always

Hotter

Does not

Want us

Not

Us

August 21st, 20:00

A few kilometres north of where we live, the prospection of lithium shows the signs of an industry ready to pursue its sole activity: extraction. An English mining company, uncannily called Savannah, is ready to begin drilling the soils of Covas do Barroso to prospect for lithium, a mineral integral to the production of batteries for electric cars. Lithium has become the new white oil (sic). In a completely false effort to re-think energy sources and produce “clean energy”, lithium-powered batteries are thought as a means to electrify “clean” and humming cars that do to disrupt the calm of European esplanades. Moving from oil to lithium seems to help the bad consciences, the petrol-stained hands of big polluters to believe in salvation, yet again. The same system with a new face. From petrostates to electricstates in a Frankensteinien effort to vivify a system in self-induced coma.

There is nothing but extraction as the modus operandi of this disenchanted West. Extract rare earths, extract lives, extract stories, extract from bodies, debates, identities, cultures. All that it sees it extracts all the while fooling itself that it can still save, order, master and control just about anything. The salvation rhetoric of the West is the opium of its addiction, not religion per se — robbed from the dimension of the spiritual — but rather the religion of extraction, the religion of civilization, the religion of control, those are the true opium of the

20:20 Another timeline replete with images, sensations, sounds and ideas that seek for a way out. Another nascent film on the surface of the screen. But how to have out if the modes of reception of these thoughts-made-cinema continue to be the fast-paced film festivals, the egotistic competitions, the vain circuits of exclusivity in encounters made from within the cool distance of an uncompromising viewing. It is hard to keep believing and feeding this tired machine of a cinema always at a distance. How to receive and fabricate a cinema of the near? A cinema of, for and with the living?

21:21 There is another cinema taking place for a long time outside of the window frame of the screen. Meanwhile, the inhabitants of the cities have been too busy to attend these daily screenings.

August 23rd, 10:11

You know, I find that it’s very difficult to talk about extraction in the domain of culture and art without finding myself trapped by the expression of ownership. How do you protect forms of fragile life without recourse to ownership? This is the difficulty that minority cultures find themselves in currently, faced with the double violence of cultural appropriation. On the one hand, their lives, their images and their presences are exploited like resources – which colonial capitalism follows in another way, seeing in all things possible resources whose exploitation must be maximized. And on the other hand, preparations are made for the trial of those who try to resist in the name of a lack of openings to the Relation, which has become the fetishistic mantra of a practice of accumulation by the North, feigning ignorance of the violence of the dispossession and toxicity it imposes on others. Here again, the minority Souths and those of the Global North, those who don’t do what is expected of them, are condemned to be treated with condescension and must accept this endless feeling of falling behind on an agenda that is falsely benevolent and progressive. The Relation in question not lacking polarity and the Body of reference from whose perspective we are required to think having simply a new way of fabricating its centrality, by pacifying social relations and the teachings of History. The fatal skill of capitalism thus pushes all humans to demand forms of ownership simply to survive, even indigenous populations for whom this very idea of separation from the living is inconceivable and ridiculous. This is something that has been much in my thought these last years. I tried to cut myself off from the toxicity that it introduces in us, following Isabelle Stengers and Philippe Pignarre’s idea on capitalism[8] as sorcery without a sorcerer that literally acts through bodies. What is experienced as interpersonal problems is in fact often the expression of systems in confrontation across different bodies. It is very difficult to pierce the surface of these quarrels in a narcissistic world where everything is brought back to the person. But we must make the effort to dismantle this diversion in order to name these tensions which bear witness in fact to forms of resistance against systems of appropriation that are profoundly integrated into the social and professional habitus of the West. Habitus that destroy collaborative spaces by individual desire of extracting the symbolic benefit and maximal material from any situation and this through the act of ownership, of signature.

From this perspective, contemporary art scenes in particular, if they have managed to create formidable spaces for the mise en relation of transnational bodies of knowledge – probably much more than cinema, whose industry is also largely attached to principles of crass ignorance – must also learn to consider themselves as problematic zones and spaces where conflict is possible and even desirable. This as means to promote the co-existence of multiple ways of composing (with) bodies of knowledge and multiple spaces to move towards. And thus to be able to choose to move from the living towards the living as a possibility of symbolic human practices. The ownership and morbidity of metaphors can no longer be the only – fatal – outcomes for art. Potentials remain to be explored by re-associating the artistic act with a profound ecology – a decolonial ecology. It seems to me that these possible directions for the practice of art and cultural forms must now find their place in schools. Because schools are places both problematic and essential. We need now to break there the cycle of transmitting strategic recipes and to open ourselves up to other forms of experimentation: empirical situations of culture that are larger and that interrogate the politics and poetics of reception, the powers of trouble and the appearance of places. And it goes without saying that all of this calls as much for new methods of pedagogy as for new forms of critique.

Disengaging from assignations without looking for positions of ownership is a bit at the heart of the exercise of presentation/dissimulation that I tried to express in my first essays on de-speaking cinema. Fleeing the scene of capture of Western documentary cinema to hide something by saturating the scenes of the visible and the audible, by literally rendering them inoperable as proof. It is therefore a “flight by remaining there”, the production of a scene of living representation rather than consenting to a morbid extraction. I have the feeling that the cinema that interests me now must produce specific opacities that are the fruit of active practices of delirium and hallucination, an aesthetic of trouble that resists imitation through the veritable engagement, the presence, that it demands.

________________

8.Capitalist Sorcery: Breaking the Spell, P. Pignarre, I. Stengers (Auteur), Andrew Goffey (Translation), Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2011

August 25th, 10:01

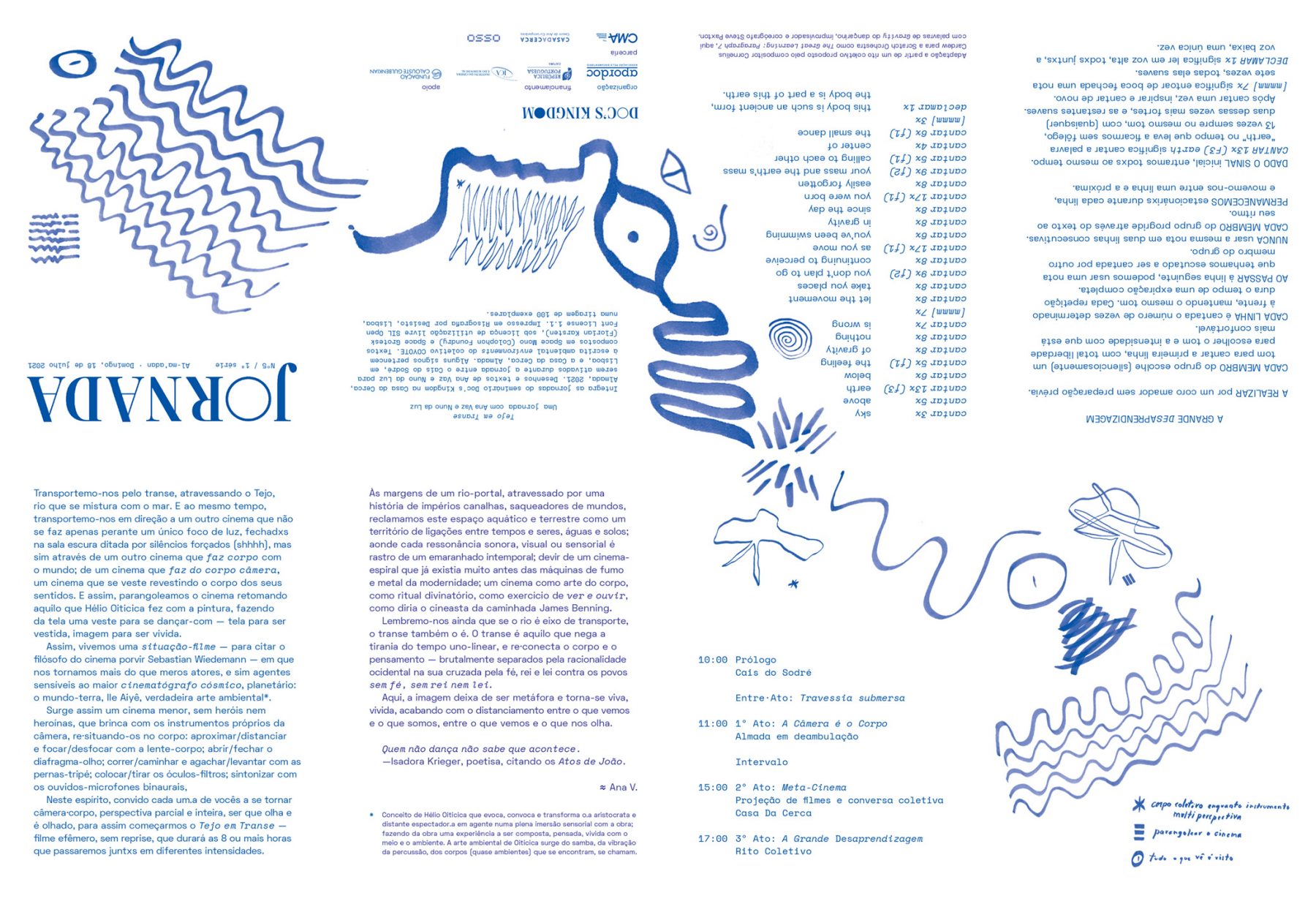

Thinking of our conversation, I wanted to share an experience with you. A few weeks ago, Nuno (da Luz) and I proposed a film journey starting at Cais do Sodré in Lisbon going into Almada, on the other side of the Tejo (the Tagus river). This was a proposal and provocation for Doc’s Kingdom[9], who since the pandemic have begun hosting daily journeys in which different practices are brought together questioning what cinema can be, how it can be made, how it can be shared. Tejo em Transe was the name of the journey we proposed (the title is a play with Glauber Rocha’s Terra em Transe). Here, rather than alluding to Rocha’s entranced cinema populated by deranged politicians in maniacal trance, we called upon a different trance, one as subtle as the simple act of walking a territory together in silence. A cinematic gesture that calls for a different cinema, a cinema made from and with a collective body, a cinema without authors.

The journey was conceived as a film in itself, a film made from within the trance of a day spent together, a film that could never be replayed. We began with a 2-hour collective silent walk in which numerous un·filmed films were made. All written in an unwritten choreography of bodies in space, of bodies driven by a mutual curiosity for this place and one another. At the end of the walk, Brás Antunes, a participant of the journey, shared the following thought: “Thinking of what we just experienced today, I think of Rocha’s Terra em Transe, of that moment in which the lead character screams: The people are not guilty, the people are not guilty. Here, I want to say: the body is not guilty, the body is not guilty”. What for Rocha was a reclamation of “the people”, for Brás and for us was a reclamation of the body as ‘the roots of a common intelligence’ that cannot be bought, nor taught, only transmitted through a certain poetics of relations[10], one that is never subjected to reason alone and evades scientific knowledge as the privileged form of knowledge. This poetics would be in and of itself a form of knowledge that knows poetry as an art of forging relationships to/with/in the world and with/alongside its inhabitants. Something that Aimé Césaire would describe as “feeling the pulse of nature, of life and also of history”[11].

In the late 1960’s, Hélio Oiticica moved away from painting fully aware of the limiting experience of looking into a framed painting hanging on a white wall. His Parangolés[12] became paintings to be dressed, danced with, lived with. It is 2021 and it stuns me that cinema seems to remain radically untouched. The same instruments for the same experience. I am interested in looking for other ways of making and sharing a cinema of/with the living — images to be lived rather than merely seen, to paragolé the experience of cinema. A cinema that can exist outside of the black box of cinema theatres. A cinema of the feet, rather than one of eyes and hands.Tejo em Transe was a beginning — or, in your words, Olivier, a rehearsal — towards a simple choreography for another kind of cinema, a cinema of the body, a cinema that is not simply a window or screen into the world.

And as we have already spoken this other cinema has existed long before the so-called invention of cinema in the 19th century. A living cinema that has always already existed outside of the West. A cinema that was played and replayed around a fire, a ritual of attunement, a reparation of ailments; a cinema that performed stories, embodied tales; a cinema of transmission made collectively on the margins of a river. A cinema that in the words of Ailton Krenak elicits “the courage to be radically alive” and not “look away from the desert, but rather to cross the desert”[13].

12:00 Exterior. Day. The arid surface of the earth weights against the walking bodies of those who have decided to cross the desert, together, in a slow and soft pace. The ensemble has no chef d’orchestre, the raucous rhythm of the walking bodies reject any pre-determined script. There is no fixed horizon in the desert, only the walking. The arid wind blows where it wants. Fires ablaze in the middle of uneven circles kept together by raving conversations with no end nor beginning. Scarcity is what holds the group. No space for abundant gestures or attitudes in a desert weak of air or food. Minor movements reign conversations without words. One must hold onto their breath. A chaotic music of feet and mumbling. The desert sees no end. Screenings are held morning until night, a way of walking through the planes. Clouds of dust spell undecipherable mysteries. Riverbeds guide the path of the fugitives. The walkers know there is no disaster as they are inside it. There is no window, nor screen. Their eyes have shifted to their hands, their eyes have shifted to the feet.

________________

9.Doc’s Kindgom is a yearly film seminar dedicated to a surveying the works of film authors through small and immersive film gatherings in different locations in Portugal. https://www.docskingdom.org/

10.Edouard Glissant, The Poetics of Relation (Michigan: Michigan Publishing,1997)

11.Aimé Césaire in Sara Moldoror Aimée Césaire, Le Masque des Mots (1987)

12.As a response and in repudiation to what Oiticica would call the Bourgeois intellect, dance became a way out of the over intellectualization of Art towards an embodied experience of Art. The parangolés were wearable garments in the shape of capes made of various fabrics and materials containing messages and statements intended to be worn, danced with, lived with.

13.Ailton Krenak, A Vida Não é Útil (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2020), p. 116 (my own translation)

August 2nd, 10:36

I’d like to reproduce here the introduction to the text “Towards a de-speaking cinema (a Caribbean hypothesis)”. First of all because it is a text that we had the opportunity to read and discuss a first time with the collective Coyote in an online conversation in November 2020 and I like the idea that texts, like pieces of music, can be replayed, even remixed, in different contexts. They take on new resonances in relation to the material situations of each context. This is an important idea for me because it goes against the obsession with world premieres at festivals, which create such problems for us. For me, if we work on a situated context for presentation, the film is always seen for the first time, in that particular way, in that poetic texture, that political climate. The fact that works are not totally autonomous in terms of the context of their appearance, the manner in which all the gestures, presences, and shadows, the chemistry of the context affect what we see and what wants to appear, is absolutely not a limitation for me, but rather a living quality of art. There is an art and a politics of reception that, to my way of thinking, goes far beyond the logic of programming. It’s a way of building a habitable space for viewing. In this way I think the introduction of “Towards a de-speaking cinema” in the form of a collective hallucination clearly establishes a kinship with these films that you tried to invoke with Nuno through the shared experience of bodies in Tejo em Transe. Finally, there is a more trivial reason to come back to this fragment of text, and I wanted to share it with you. It’s both trivial and very significant. When I proposed the English version of the text to a performance and cinema magazine, the editors asked to make cuts so that it would correspond the available space in the magazine. I didn’t know how to do that because for me, the text created a path, an errant wandering toward certain disturbing feelings, and that path spoke eloquently, in part because of its very structure, of the doubts that had plagued me as I wrote the piece. It was a speculative act with a degree of delirium. For the editors, it was clearly a question of keeping only the parts of the text that in their opinion spoke the most directly about cinema and they immediately proposed deleting the introduction, which for me was the most obvious occurrence of the kind of cinema I was seeking…

A hallucination

Nocturnal flight. Cold feet in the humus and roots smoothed over by the thousands of footsteps that have caressed the once rough surface. He leaves behind him the lights of a dwelling to move into the unknown obscurity of a forest. Forever. He thinks, “I’m leaving forever.” He sees, he believes he sees. But he’s no longer sure of anything. Perhaps an arm, a hip, maybe a hand, a silhouette of leaves, or a twisted tree that runs. He doesn’t know where he’s going, he doesn’t know what he’s throwing himself towards. He has no words. He runs, feels, cries out. He is delirious and frightened. Something inside him is dying. He must lose his words. And he must find words, with a world that is there, before his eyes. He lets himself go. He licks his sweat, swims in his saliva and the oil of his muscles, strikes the skin of his stomach with broken tibia bones. His head is full of the sound of insects climbing up the optic nerve and sliding toward the moist surface of the eye. He no longer knows how to cry. Others are there like him, lost, haggard. Like him, they have left, they have removed themselves, untied, divested, stripped themselves of a life of repeating the gestures of death. Now, there is a new time. Now they do not know where to go or how to inhabit this time and this world with all that is there, intensely there. They do not know if there is a place where they could lay down their heads, a cool place where hands would lightly touch them cover them with mud, leaves, smoke. They cannot see each other, cannot manage to see each other. Their teeth clack and they tap on their calves. They see each other now by means of all the dull noises a body is capable of making. They discover all of their eyes, open to the surface of the skin, and taste all of their orifices. They reach with these eyes into the emptiness until they feel each other, for they cannot do it alone, alone they cannot raise up these first images of a cinema for the self. They touch each other now via the moistness of all their eyes, which are also hands, hips, buttocks, and necks. Huge drops of sweat in which a human could stand upright serve as magnifying glasses through which the infinite details of a night-blue vegetation can be seen. With no declaration, before the first words, they dance a swarm of hallucinations that rise up and cross through them. Caribbean. It could begin somewhere else. It begins everywhere in the peripheries of the visible world. On a European beach in the green dawn of the Mediterranean, where the living dead smoke a first cigarette without reprieve, in a far-flung suburb where black breath and sweat slide off the hands of the police, at the edge of a mine, open-faced to the sky, in a forest in flames where columns of minuscule beings march off towards nowhere and dive back into a dreamtime that the delicate eye of drones cannot see. They share a cinema of bare life, they hallucinate another life.

Olivier Marboeuf’s passages were originally written in French and translated into English by Liz Young.

Ana Vaz’s passages were originally written English and Portuguese. Translations are her own.