At Least 23 Worlds

A conversation between

Denilson Baniwa and Ana Vaz

24th of August 2021

São Paulo, Brazil / Lisbon, Portugal.

Ana Vaz: Denilson, I’m very happy and honoured to be able to talk to you. Thank you for your time and your open spirit. I’m thinking about our conversation today in shadow of your talk A mátria contra o Estado piromaníaco [The Motherland against the Pyromaniac State] organised by Jaqueline Martins Gallery with curators Mirtes Marins de Oliveira and Lisette Lagnado in which you develop a significant counter-narrative to the discourse of “heritage” loss due to the devastating and recurring fires in Brazilian public museums, collections and archives saying that from an indigenous perspective, the fires meant above all “the impossibility of rescuing stolen artefacts” — an essential dimension that goes beyond the very Western desire for preservation. So today I want to propose that we return to some of the issues you addressed in that talk and also to talk with you about cinema, about your relationship to cinema and video.

For The Living Journal we are working on the idea of sowing the seeds of a living journal that looks for a living cinema. We are looking for ways to dispel a particular frustration with traditional cinema as a perpetual form of estrangement from the world: cinema as a window. And so, we’re asking ourselves: how to imagine a cinema that brings us closer to the world?

We speculate that this “other cinema” already exists and was not invented in the 19th century, with the steam and steel machines of modernity, but, instead, we think that it has existed since we have told stories around the campfire, since the trees began to move. And while thinking about all of this, I receive your films and videos as a gift, as the rush of a river. I’m thinking of your very first video, Niterói: Águas Escondidas [Niterói: Hidden Waters[(2011), a cinematographic stroke of immense strength and simplicity. It’s as if the camera became an extension of your body, the zoom almost touches the waves. And suddenly, when we see Niemeyer’s modern art museum in Niterói, we understand the shock of modernity’s arrival as, in effect, a spaceship. This alien apparition seems to unfold throughout your work as a motif that haunts it. I thought it would be good to start our conversation with this: cinema and aliens. And to ask you simply how did cinema – if that’s what you call it – appear in your life?

“Contatos Imediatos de Terceiro Grau” [Close Encounters of the Third Kind], 2021, digital collage, variable sizes

Denilson Baniwa: I remember perfectly the first time I went to a real cinema; it was in 2005. It was a feeling that I’d never known or imagined. And I became addicted to the cinema! Before that, I’d already attended a more informal cinema screening, in 1999 or 1998, which was also a very powerful experience. During the political campaign for the election of the governor of the State of Amazonas, an open-air cinema screening – which was actually more of a rally – was organised in a central square in Barcelos, where I lived. That was my first experience of a potential cinema. And it lasted a week, I remember all the films… It was a real delight for the children, and I was there in the middle of it, also fascinated. I was very impressed by the immersive effect that a giant screen and loud sound can have on us.

I also clearly remember the first film that made an impression on me, Alien. In fact, it still leaves a mark on me today. I like to re-watch it and imagine multiple layers that may stem from it, specifically recently in a piece for ZUM Magazine about my relationship with the image. Because it was an extremely powerful experience: I was really scared of something that I knew wasn’t real.

Anyway, from those experiences grew a feeling of admiration, and I tried to understand what that process was all about. Particularly at the Communications Faculty, where I began to better understand some aspects of filmmaking. You spoke about conversations around the campfire… I think [Walter] Benjamin helped me to connect some things. Through cinema, through the act of telling stories in a different way, which stimulates the imagination and emotions, I began to see some things about my community in a different way. I realised that the old man in my community who used to sit and tell stories to the children sat in front of him, perhaps he was like a cinema screen telling us stories! In short, cinema, the visual expression of the moving image, has always been very important to my development.

AV: It’s great listening to you, it leads me to think about the relationship that each of us has with this immersive technology that can be used for both wonderful and terrible things, this surface of light and glimmer that is cinema with its quasi-hypnotic effect which can inspire fear, joy, and lead us to share something with beings who are not really there, but in some ways are…

DB: These characters, above all in the fiction and sci-fi films that I like, I imagine that they’re like entities which circulate in the same world as us, but perhaps invisibly, extrapolating our world. I think that being able to imagine other worlds from the creative process of fiction is something incredible. I have always been really inspired by the process of going to the cinema, and films such as Star Wars, horror films… They are films which captivate your emotions.

AV: When you mentioned horror films, I immediately thought about your video Tamuia [2021] as a genre film, a horror film. The way in which you run with the camera, like a fleeing body, the images that tremble. Your films seem to play with cinematographic genres. And now, hearing you talk, I understand better your passion for horror and sci-fi films, a passion that I share. Genres and a certain irreverence towards genres seems permeates a lot of your work.

DB: For me, horror films, more than others – at least the ones I know – don’t reveal things explicitly. They’re like a peephole, they keep weaving a feeling…. I am thinking of some of the films that have been formative for me, like Nosferatu, Dracula, sometimes, due also to budgetary constraints, these films explore the scenery, the camera’s movement, and other tricks, without showing the villain right away. I really like to make the viewer start to try and imagine what’s not in the image.

AV: It’s true that in horror films we are kind of walking in the dark, it’s one of their great qualities. I believe there is something opaque and cryptic that’s very important to preserve in a narrative, a form of camouflage, of protection. And I feel this in the way your images are constructed, the messages are clear, but they’re never given all at once. You take us on a journey, meandering.

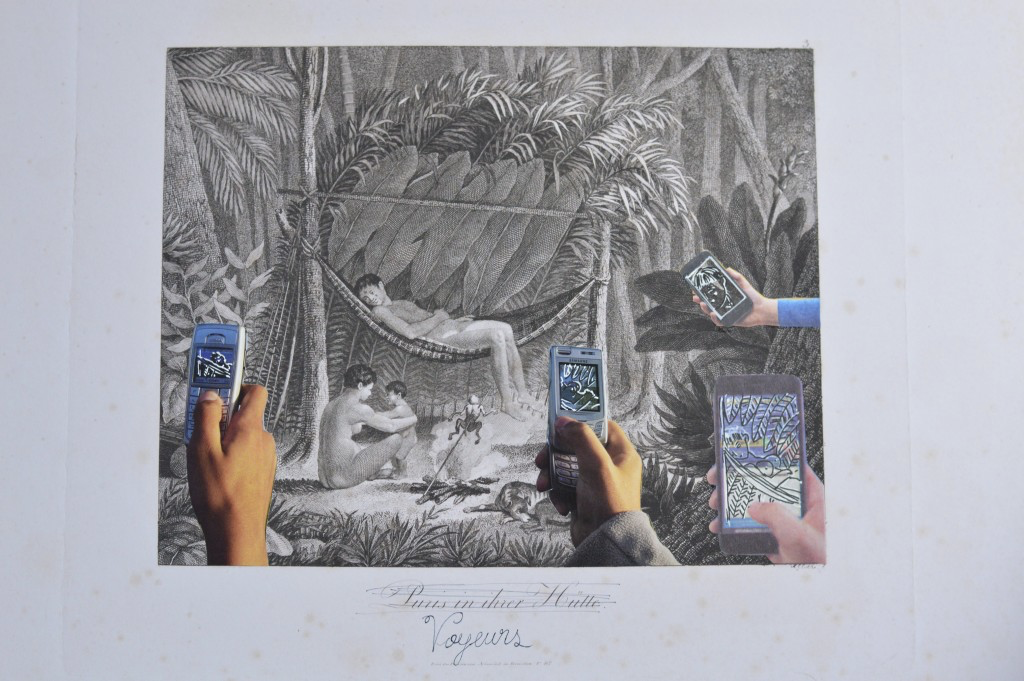

DB: I’ve now remembered the work Awá uyuká kisé, tá uyuká kurí aé kisé irü [Quem com ferro fere, com ferro será ferido/He Who Strikes with Iron, Shall Be Struck with Iron, 2018] which plays with these ideas about how the same tool can be used. Taking a selfie with a work of art, while the work of art is recording you at the same time. Who’s capturing whose image? The tool serves many purposes, but it can also be used as a response, as a confrontation. And of course, the most obvious, for a narrative dispute. Everything is explicit here, but it is not a violent confrontation. It is talking like this: look, there was a time when you used to come here and capture everything, but now we have learned how to use this machine, and we can also capture you.

“Awá uyuká kisé, tá uyuká kurí aé kisé irü” (quem com ferro fere, com ferro será ferido), 2018, acrílica sobre tecido, 1,60 x 2 m

AV: I’m glad you’ve mentioned this work, which, initially, was from where I wanted for us to begin. It’s an immense work, not only because of the clarity of the message, but also because something very powerful emerges from the fact that you mention iron. I can’t help but think of iron as something that the machines themselves are made of: photographic or cinematographic machines are made from this material extracted from the earth. So, for me, this work is also about extraction, the extraction of an image and how image in Western culture ‘has become a synonym for conquest’, this is something you mentioned in your talk A mátria contra o Estado piromaníaco. And of course, cinema has historically been complicit with this form extraction as conquest, a part of the colonising project. For example, the Lumières organised expeditions all over the world, making images as trophies in a constant and violent separation between those who film and those who are filmed.

So, keeping this in mind, Quem com ferro fere is a work which punctures the history of cinema. My question about this work is around the relationship between the image and the wound, that is, in the sense that the image also wounds. And so I ask myself and you: what does an image in the restorative process? Can we still think of images as instruments of repair?

DB: I think everything is possible. Something I’ve thought about a lot is a talk by Ailton Krenak who – during a phase in which I was working very aggressively, with a need to speak out – gave me a kind of “pull on the ear” and advised me to rethink the ‘conditions of apparition’ as being something important for creating potential alliances. Because not all of the white world is the enemy. I kept thinking about this, and also about his talk on affective alliances. I’m now thinking that what the construction of the image manages, or could manage, to do, could be based on these affective alliances. For example, this meeting of ours, which as a Baniwa person[1], I don’t believe is random: at some point in our lives our affects crossed, it could have been just that one chat and each of us could have decided to go their own way. But we decided instead to have a conversation. Together, we could maybe create restorative images, or perhaps more than that, we could construct images that re-open badly healed wounds, which is also a way of healing. We are so used to seeing images that are plasters stuck on top of wounds, sometimes it is important to take the plaster off and treat the wound with antiseptic or stitches, reconstruct the healed scar. And, that is only possible together. I think it is important to construct images that are not necessarily restorative, but that are important in the process of reparation.

________________

1.The Baniwa are indigenous South Americans, who live in the Amazon, in the border area of Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela.

AV: Absolutely. I’m moved by your words. This is a topic that affects us since we know that we carry these wounds and that we live in a society that violently wants to erase and hide these wounds. I say this from the perspective of being born in a modern city (Brasília) that has historically and symbolically wished to deny History through its own prophecy. Yet, I have always felt haunted by something that should be there and wasn’t. And so, for me, filmmaking became a way to dig up the ground in search of what’s been hidden, in search of the wound. And in this process, things begin to manifest without our choosing, since there are always elements, forces and narratives that need to manifest, and I agree with you that they are not at all random. That’s why I was very moved when, in the middle of your talk A mátria contra o Estado piromaníaco, suddenly terra preta[2] appears. And, for me, terra preta is a bit like that, an underlying layer of a restorative process. Terra preta is a library made of earth, the result of centuries and centuries of enormous effort to care for the land, what Ailton Krenak, quoting Chief Seattle, calls “treading softly on the earth”. It is difficult to capture terra preta as an image or representation, but it remains a living archive of pre-Columbian America. Meanwhile, we live in this age of fire, in which the world’s greatest libraries, which are forests, burn every day, as do museums, collections and archives. And in this time of so much devastation, it’s necessary to think beyond devastation… And terra preta seems to be a powerful element of this process of restoration and healing. After all, after the fires, all that’s left for us is to sow.

________________

2.Terra preta [black earth], terra de preta de índio [indigenous black earth] or Amazonian terra preta is a compost of anthropogenic origin that was cultivated in pre-Columbian Amazonia by indigenous societies before the European invasion. Highly fertile, this soil has an unprecedented capacity for self-regeneration. Since the 19th century, studies on terra preta have disrupted the ethnocentrism inherent to the colonial mentality that sees the Amazon as a “virgin” and “wild” oasis unpopulated of complex agricultural societies. The presence of Amazonian terra preta in the forest contradicts this vile myth.

DB: Listening to some of the voices of our time, you realise the despair we’re feeling, because it seems that we don’t have the right conditions to redevelop, to rebuild some things. The fire at the National Museum was one of those moments of despair, I was in shock and I’m still mourning today. With all the meaning that goes with a fire. And thinking about this despair caused by the fires, the destruction, the government, the deforestation, all that, I remembered some Baniwa stories that describe other mythological fires that have already happened. Although hope is almost non-existent, since fire devours everything it can touch, even so, there remains a possibility of reconstruction.

For example, we can think about how a part of the forest is burnt to create a field, which is a technology of resistance and human survival. The terra preta is the sign of human presence in that place, layers and layers of soil that are the remnants of human occupation. Some 5,000 years later, knowledge is discovered that wasn’t even known to exist there. How can we imagine a reconstruction based on these traces, the ashes, the ruins? In the West, people have placed enormous importance on collections, thinking that the objects and knowledge would remain there forever. Too much trust was placed in this method of storing data, and then fire comes along and says: “it’s not like this, I’m going to burn everything down”. And terra preta is the opposite of that, isn’t it? A living memory, a library, a database that’s been alive for 5,000 years. With a different way of cataloguing, right? At the same time, it’s a chance to think about reconstruction. There are things we’re not going to recover, like the Marajoara ceramics, because fire destroys everything. But through the metaphor of the terra preta, we can find the means of reconstructing other ways of narrating history with layers of ash, twisted metal, earth, burnt wood.

AV: It’s really meaningful to think that these Marajoara ceramics were themselves made of earth, right?

DB: Exactly. Speaking of cinema, the tripod used to be made of wood, iron is extracted from the ground and becomes a machine, glass is also sand: it’s a whole process of exploration-reconstruction. And the possibility of return, which can happen both in images and recordings, as the material itself can always return to nature, nature can take it back.

AV: Returning to its original form though never remaining the same. Thinking about this, and coming back to the alliances that we were talking about, zones of contact between “irreconcilable people” as my father would say, I’d like to share one of his reflections with you. He was a composer and lived in the Amazon with the Zoró people, from whom he learnt a lot. He wrote a text called Nós somos o coyote [We Are the Coyote], which has been a guiding star for me for many things, but also in regards to memory. The text is a response to a work by Joseph Beuys [I Like America and America Likes Me, 1974], in which Beuys encloses himself with an American coyote in a gallery in New York, for seven days, in order to see through the American coyote. Regarding the work, my father writes that the piece will always be incomplete until when the American coyote is taken to Europe, with all the precautions possible, and ‘the coyote would stand next to a museum or gallery, perhaps in Rome, and next to it would be the great white man who writes books, philosophy and operas, but who still doesn’t dance. The man who thinks that art is outside of him, in a painting, architecture or installation’. And he ponders that the ‘indigenous people of the Americas do not keep objects, only their spirit, their design. They can be remade indefinitely. Because of this, there is no indigenous museum capable of reproducing their symbolic world. There is neither a Stradivarius nor a single instrument that is real, but a way of thinking, an idea transmitted, which cannot be bought, only learnt. He ends by saying, “We are the Coyote, we, artists of the Americas”.

I think it is curious that he considers it “impossible” for an indigenous museum to exist, I’d say that it’s impossible that the museum form could ever contain the memory of the living world. It leads me think that things can be transmitted, but not sacralised, as they transform endlessly, and for that we need the body, life, movement as a means of transmission, don’t we? Perhaps we need the body much more than screens or walls.

DB: I’d love to read your father’s piece. Recent indigenous production perhaps centres around this very point of translating that which cannot be literally translated by displaying an indigenous object in a museum. Contemporary indigenous artists are like shamans who manage to create movement between worlds and find ways to communicate in other non-traditional ways. I can’t answer for all peoples whether an indigenous museum would be possible. But from my Baniwa origins, there is an interesting story I’d like to tell you. Once, a Baniwa elder was taken to a museum in Pará, he got there and started talking to the objects as if they were his relatives. And indeed, they are. He talked to the objects as he’d talk to a human. So, I started to think more about what the objects represent. For example, your father is a musician and a good example to illustrate these issues with and understand why Baniwa musical instruments cannot be held prisoner inside a gallery. Each Baniwa instrument is a living part of those beings who invisibly coinhabit the world with us. For example, the japurutu flute is the femur of a Baniwa entity. When you play this instrument, you’re using that bone to reconstruct what that entity made at the beginning of the world. After the ritual dance with the music, the instrument is returned to the river, where it is kept. So, in fact, they are living instruments, instruments that are parts of bodies that materialise in a world that we live in and cohabit in a material, physical way. But when they’re returned to the river, they go back to being invisible spirits. Based on this, I can’t imagine a Baniwa museum, really. Because imagine I take one of these flutes and leave it locked up in a display case, far from where it lives, without returning it to the river, it’s as if I’d left the Baniwa entity in the river with one leg. [laughing]

These objects are alive, they are part of other bodies, which only lend themselves to us because they want to dance with us. So contemporary art is like a different way for this being to transit worlds. It’s like cinema: an actor or actress lends their body to make something invisible come alive.

AV: Beautiful story. It’s true that there’s something ephemeral and temporary about cinema as an experience as well, something that can only exist in specific conditions. Watching a film in a specific cinema, or in the open air in Barcelos or in an underground film club is always a different experience. It’s never the same film, it’s always the result of the ‘conditions of apparition’ (to go back to Ailton Krenak) of these images.

I often say to my friends who programme cinema that this concept of a film premiere is a fallacy, for each viewing is always a premiere, a film is always only watched once, in a specific place, with the people who are there, and with whom emotions that go beyond language are shared. This is something very powerful with regard to cinema. Cinema allows us to see with wider or smaller eyes, changing our perspective. We can think of it as innately animistic: transforming our relationship with the different dimensions of time and space. I also think cinema is a great way of performing, rehearsing how we hold on to memories.

I don’t have any way of not mourning and being extremely outraged about the loss of films, those that burned in the Cinemateca and those that will possibly burn in other fires. But there’s something in that sorrow, as if fire were the absolute end, which also seems sort of reductive, because I believe that everything comes back. So, what can we do? Maybe we have to re-record them, remake the films, create other versions of the films that burned from the corporeal memories that we hold of these films. I’ve remembered how you evoked the entity of Yebá Buró, of her relationship with memory. You said that, for the Baniwa, there are at least 23 worlds and Yebá Buró is the entity of memory, the entity that created this world from her memory. And so, we live in a world that is the memory of another. This is really beautiful.

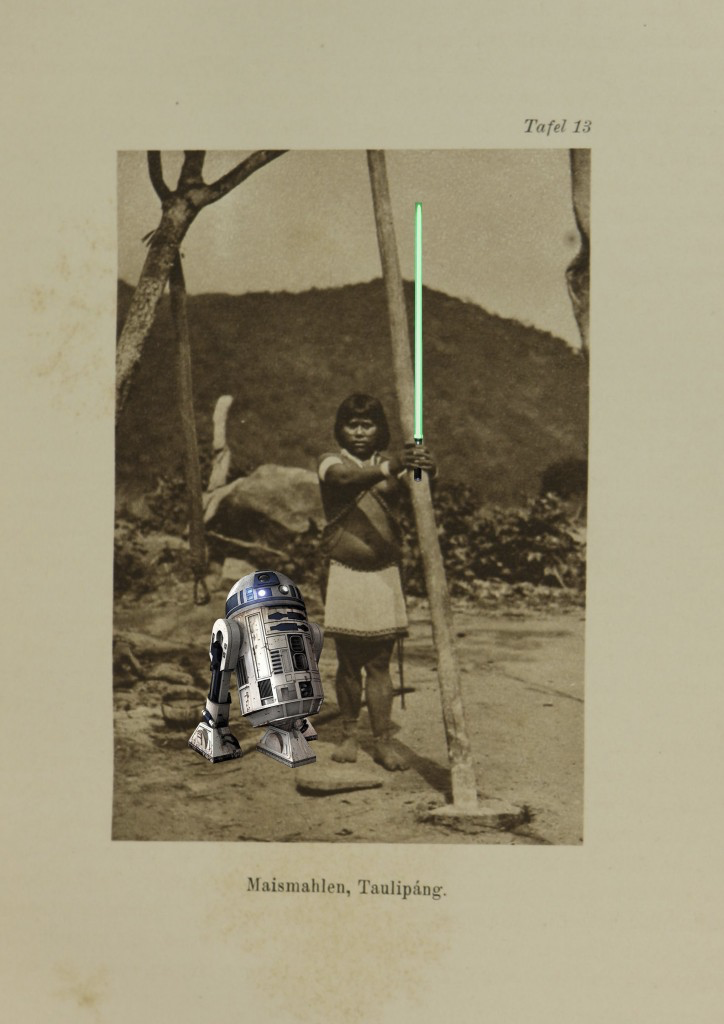

DB: [laughing] In fact, 23 worlds. Now I’ve remembered a trailer of one of these Hollywood superhero films, which talked about multiverses and heroes that travelled through them… And I thought “well, we’ve had this film script for a long time!” But to answer your question, I’ll use the example of another entity that, for me, seems to effectively illustrate this capturing of time and memory. I was at an event with a Macuxi friend, the area that the journal of Theodor Koch-Grünberg documented, which inspired Mário de Andrade to write Macunaíma[3]. And my friend was asked if it was cultural appropriation for Mário to have taken this Macuxi entity. To which he replied: “No, Macunaíma is a timeless entity, other-worldly, he can travel in time. He was in 2022 at the centenary of Modernism, and he saw us there, Indians amongst all the people. And he thought that this would only be possible if he allowed himself to be captured by Grünberg, and then by Mário de Andrade”. Yebá Buró and Macunaíma are entities that understand the time and space of things that happen very well. Sometimes, they allow themselves to be captured so that things become more amusing in another episode, perhaps. So that another direction is taken. If Macunaíma hadn’t let himself be captured by Grünberg and Mário, we probably wouldn’t be discussing contemporary indigenous art today.

Sometimes I used to get really upset with the anthropologists and ethnologists who came and started filming our community. In fact, it is a violent act, an invasion of privacy. Confronted with my rebellion, some old people said: leave it alone, maybe this will be of some use, even if we don’t yet know what.

________________

3.Macunaíma (1928) is a novel written by modernist writer Mário de Andrade which marked modern Brazilian literature through a caustic and distorted reading of the Macuxi myth describing the entity of Macunaíma.

“Voyeurs”, 2019, Desenho e colagem sobre impressão, 40 x 51,5cm

DB: Let me tell you the story of Ney Xakriabá. He decided to research the ancestral practice of Xakriabá ceramics, which nobody in the community knew how to do anymore. The truth is that the only information he found… was in the ethnographic films! He put together various film clips, to understand the type of earth or clay used, how fire was used, how they sculpted, everything. Now his family and community are making ceramics again, teaching others. Which is incredible. This is a turning point through the medium of cinema: it’s a right of response, it’s a reclaiming that rethinks a long history.

That’s why the burning of all these cultural institutions, from the one that keeps the Marajoara vases to the film archives, is so dramatic. Because when you lose those documents, you also lose the right to reclaim them. If we’d lost the films that Ney Xakriabá consulted, we would have lost the possibility and the right to reclaim them.

AV: Wow, that’s a wonderful story about the “possibility of rescue”. What impresses me the most is that often there’s an immense sorrow for the loss of libraries and museums, but there’s not an understanding of the possibility for life beyond the museum’s lifetime. When these images return, they’re autonomous forces, with their own agency, which are not limited to the choices of the person filming. Because there’s a belief that whoever is filming has control over the image, but this is a lie. Or that when we film, the person we film cannot look at the camera, which is another absurd rule of film schools. In other words, the West is always trying to tame images and to make them captive, and hence to tame the subjects and make them captive too. This is an essential dimension for thinking about the question of fire: that there’s a time beyond the time of the institution. Institutions are not eternal. As (Davi) Kopenawa himself says, the white man’s great problem “is that he thinks he is eternal, and only dreams of himself”. And in sake of the kingdom of One, breaks with the possibility of other worlds, leaving only the impression of a single world, always on the verge of apocalypse. An apocalypse that we do not seem to want to understand that we are already inside of.

DB: As I wrote in my article for ZUM Magazine, using cinema as a reference, the West has done so much that it’s afraid of the payback for everything it’s done, that’s why it creates these monsters that terrify human-like beings. Usually, monsters come from these wild places (King Kong). They’re nature’s answers to how much it’s been exploited (Godzilla, who was created from the atomic test). Or even from the outside, we’re so obsessed with going to Mars that we are also afraid of Martians coming here!

De Volta pro Futuro” (Back to the Future), 2021, Digital Collage, Tamanhos variáveis

AV: Wonderful eco-horror films!

DB: Totally! I don’t know if it’s part of an anti-ecological campaign. Generally, villains or monsters appear in response to environmental defenders or to nature itself.

AV: Yes, and always under a logic of salvation. I just remembered an iconic film scene from the most recent Godzilla, made in Japan after the Fukushima nuclear meltdown in 2016. In this version, Godzilla is more than one monster, he has three or four heads and multiple tails, and no one knows what the core of this monster is. While he brutally destroys roads, buildings, public transport, the whole of Tokyo, a group of politicians in suits locked in air-conditioned offices with several machines try to find technological solutions to what’s happening outside. I think this is a powerful metaphor.

DB: During the pandemic, somewhere in China, I saw images of flats that had been left empty where the decorative plants had practically taken over the building. I don’t know if you saw it, but it was impressive. Nature’s response, we just don’t know what it might be, because we don’t give it time.

AV: In your video “Ty Ty: memórias de beija flor” [Ty Ty: Memories of a Hummingbird] (2021), you describe life in the city and say: “today I wanted to dig between the cobblestones and sow a forest”. I feel that, with this film, you embrace the city as a potential future forest. Or rather, you don’t deny the monster. This film seems to me to be a great journey and synthesis about this possibility of loving the monster.

DB: Oh, Ana, if we create the monster together, we’ll take on the paternity and the maternity of the monster, won’t we? In this film, I talk about the bookshop, and what is the bookshop? Nothing but a big forest turned into stories, the books are parts of trees. The leaves of the trees, the pages of the books. And the book is the bark of the tree transformed into stories that enchant us, that touch us, that we share, from which we learn. And for bookshops and fiction to exist, we need trees. The possibility of reforesting so that our stories remain free. We still need what is natural. To become more like trees. To pick up a book and read under a tree. Learn from the trees.

________________

Transcribed by Catarina Boieiro

Translated by Katy Carroll