A generative archive

Kaba Tounkara (left) and Bouba Touré in the bed of the Senegal River, Somankidi Coura, Mali, 1977. Photo: Bouba Touré

The farming cooperative Somankidi Coura was established in Mali in 1977 by 14 people, all of whom had activist and migrant-worker backgrounds. They had first met in Paris at the Cultural Association of African Workers in France (ACTAF), a collective established to support ongoing liberation struggles in former Portuguese colonies in Africa and the migrant-workers’ movement in France, which was seeking better living and working conditions. Following repeated droughts in the Sahel during 1973 and 74, the group began to think of alternative economic and farming practices for the region’s villages. After taking up agricultural training internships in the French countryside, the workers then travelled to the Senegal River near the Malian city of Kayes, a crossroads of migration, in order to set up the cooperative. Local authorities, in agreement with the villagers of Somankidi, gave the group 60 hectares of land. The land was situated opposite an agronomic research centre housed in a former colonial plantation for sisal and a state collectivised granary built during the socialist regime of Modibo Keïta, Mali’s first president. Of this land, 25 riverside hectares were turned into polyculture gardens fed by a common irrigation system, while the rest was used alternatively for pasture (during the dry season) and farming (during the three months of hivernage, the rainy season). Somankidi Coura (meaning ‘the new Somankidi’ in Bambara), by now a village of 300 inhabitants, rapidly became a regional model for other migrant-return projects or local farming groups. The cooperative also cofounded the free Rural Radio of Kayes and a regional farmer network, two institutions ‘led by and for peasants’, with educational programmes held in different languages, including Bambara, Soninke and Fula.

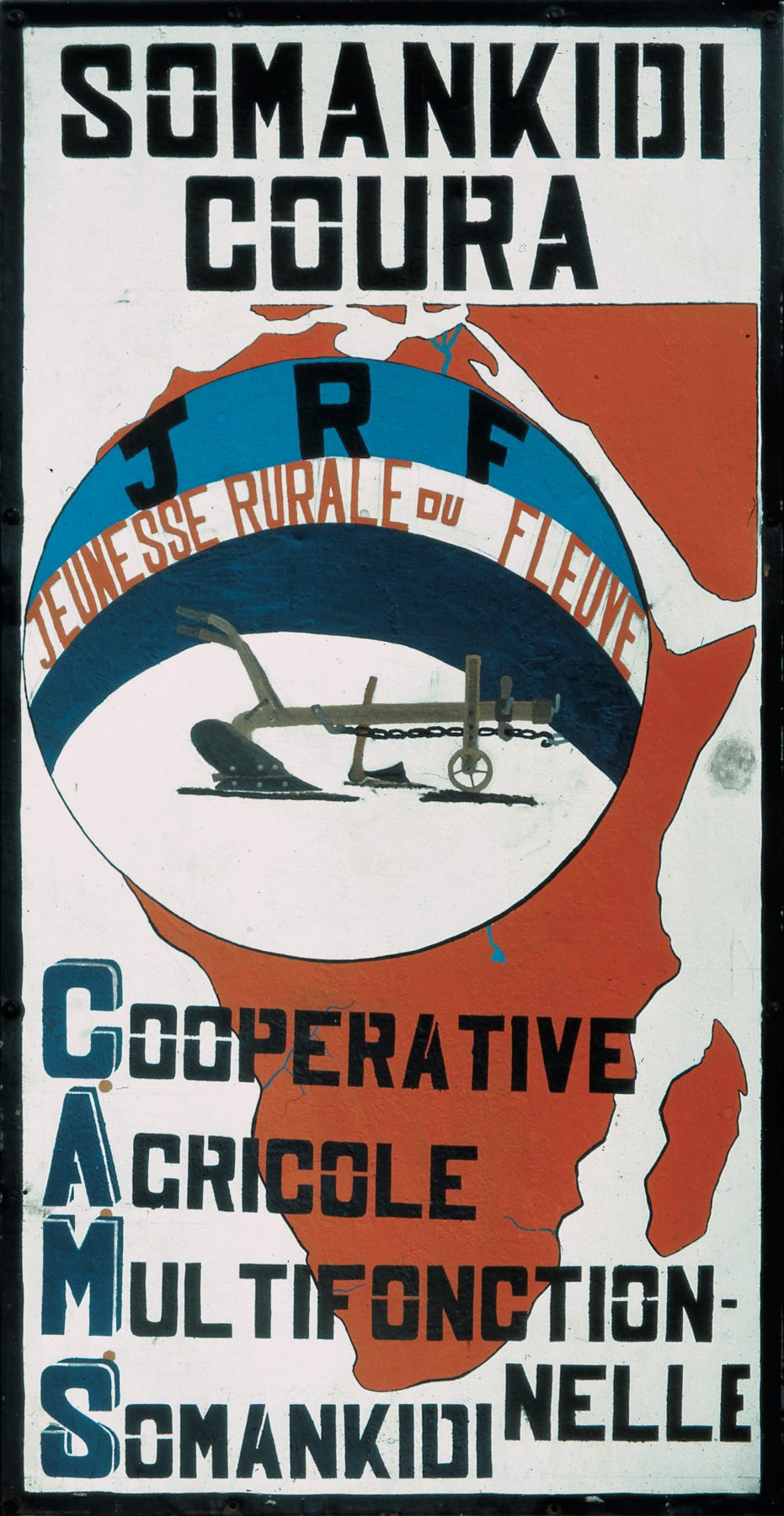

Billboard for the Somankidi Coura agricultural cooperative, 1980s. Photo: Bouba Touré

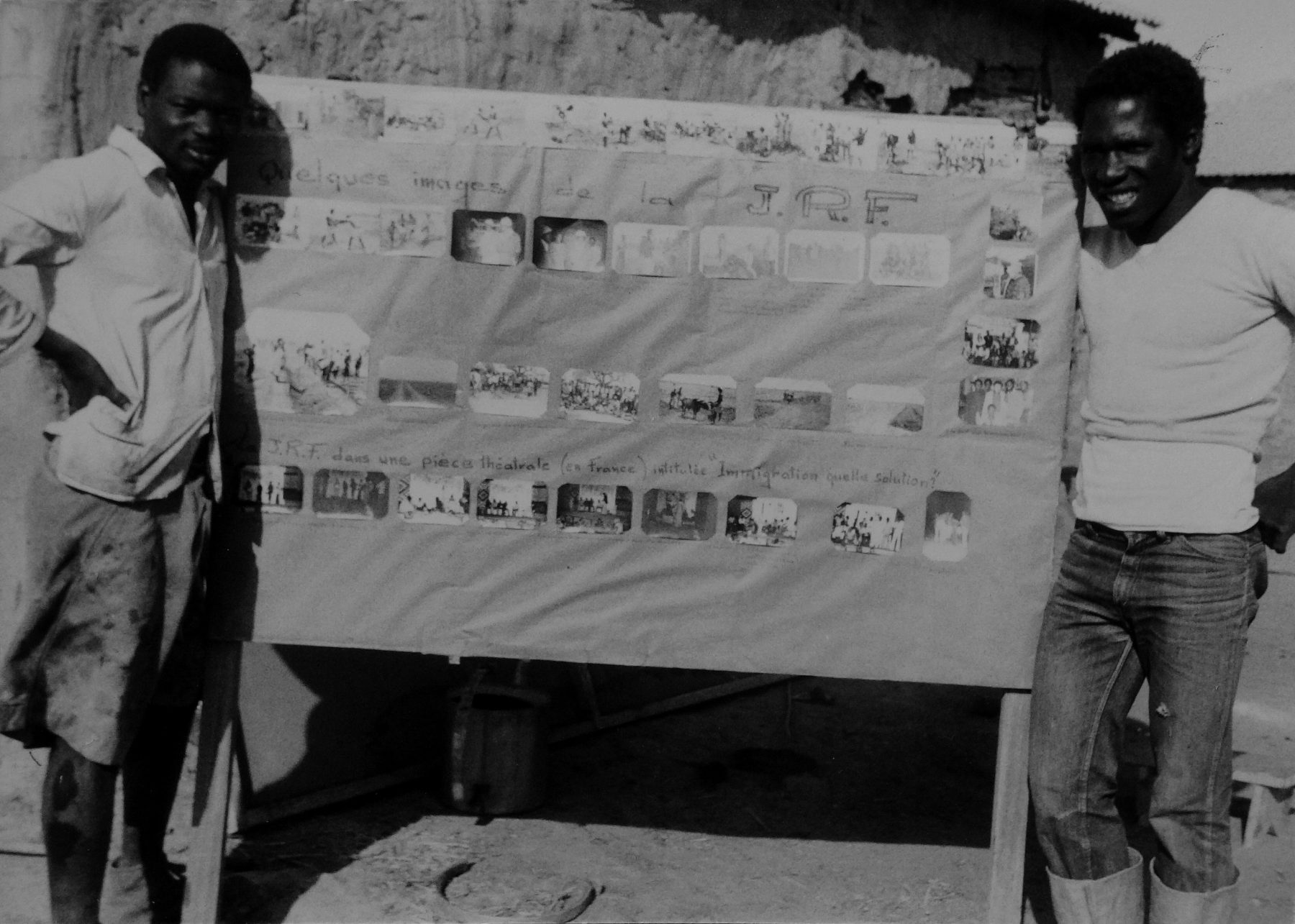

Documenting migrant workers and other sans-papiers struggles were early items on the agenda of collective cofounder Bouba Touré, who during the 1970s had begun photographing his foyer (migrant- housing block) in St Denis in France. Later, working as a projectionist, he met filmmaker Sidney Sokhona and participated in the making of Nationalité: Immigré (1975), which dealt with struggles in the director’s own foyer, rue Riquet, in Paris. Both Sokhona and Touré were influenced by the films of the French-Mauritian director Med Hondo, and their work sits in dialogue with members of Cinelutte, the filmmaking group born of May 68, and other similarly militant filmmakers whose work focused on migrant-worker struggles. For this generation, it was about claiming a position within the worker movement and activist cinema, but with a specific agenda and specific claims, in a dreadfully racist and neocolonial context (this was only a few years after the Algerian War), and to connect to the ongoing anti-imperial and anticolonial liberation struggles on the African continent and elsewhere. ACTAF may have been a cover for militant activities in support to the liberation struggle in Angola, Mozambique, Cabo Verde and Guinea Bissau, but we should not forget the role of culture in those fights. For Maoists from the French petite bourgeoisie aiming to follow the precepts of the Cultural Revolution or from Front Culturel (a cultural and political movement denouncing Senegal president Léopold Sédar Senghor’s neocolonialism), even for political leaders such as Amílcar Cabral, culture and agriculture were understood as political tools for liberation. As these struggles intersected with a learning process centred on image-making and cultural activism, Somankidi Coura’s members grew to reflect on the circumstances of their own exploitation and the means for imagining new futures. Inspiration came in forms set out in cofounder Siré Soumaré’s book Après l’émigration, le retour à la terre (After emigration, a return to the land; 2001); from another Sokhona film, Safrana (1976), a speculative fiction that envisioned the group’s settlement in Africa; and from the play Immigration: Which Solution? (1976), performed in migrant-workers’ dormitories by members of ACTAF and contextualising the proposed return to Africa.

The story of Somankidi Coura comes down to stories of displacement, and their subsequent unfolding into a movement of thoughts: forced migration from countryside to city, from south to north, the colonial capitalist production regime following in the wake of slavery; followed by a repositioning through self-education and political activities in France, in relation to liberation struggles and Pan-Africanism; to a militant and pedagogical return to the south and the rural, facing climate disruption and neocolonial conditions.

The desire to produce traces, a memory of the migrant’s journey, was part of a decolonisation process, just as necessary as the deconstruction of the neocolonial form of agriculture and governance in rural areas, and the questioning of the role and practice of the peasant and herder within the liberation movement and society at large. These stories were mostly missing from national narratives, which often assimilated the ossified social classes and categories inherited from colonisation, or instrumentalised them, instead of attending to their transformation and moving forward. After independence, migrant workers were often considered traitors to the national project; peasants were given the role of protosocialist communities within the African socialist nation-state building, but were almost never consulted to define new agricultural programmes.

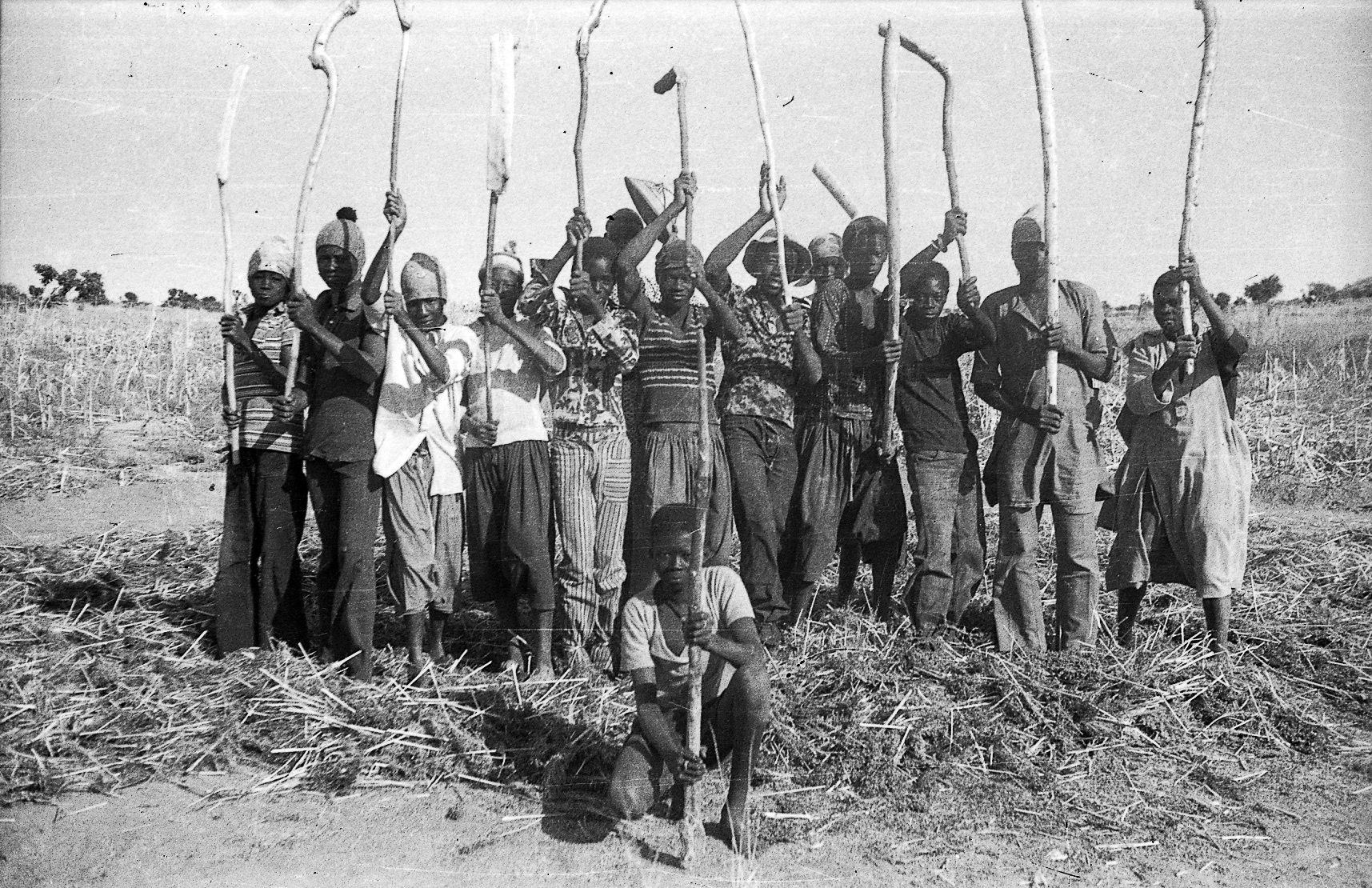

Preparation of the land, Somankidi Coura, 1978. Photo: Bouba Touré

Threshing the millet, Tafacirga, 1976. Photo: Bouba Touré

Seed nursery, Somankidi Coura, 1978. Photo: Bouba Touré

Gardens, Somankidi Coura, 2015. Photo: Bouba Touré

During the Sahel droughts, which brought famine and accelerated the rural exodus, ACTAF members, who were all from rural backgrounds in the West Indies or West Africa, recognised the necessity to reflect on the system that brought them to where they were and to take the problem at its roots. The colonial extraction of the soil, the monoculture cash-crop politics in many countries after independence and the exploitation of labour forces were understood to be at the origin of the Sahel famine, but also of their own journey as migrants.

There was an urge on Touré’s part to tell the history of the people of the Senegal River, peasants, fishermen or herders, Soninke, Fula or Bambara. To speak about the traditional family gardens near the river, and the millet and sorghum fields that did not produce enough to pay the colonial taxes. To speak about generations of kids who were sent to do seasonal labour (Nametan), to work on the peanut cash- crop fields sometimes a thousand kilometres from home to sustain their families; about the subcontracting of the herder population to harvest gum arabic for colonial trade companies, and the displace- ment of entire populations for forced labour in colonial plantations, product of the intense slave trade along the river. What could be done in the village to give people the opportunity to sustain themselves, to fight the drought when it comes and to think of futures other than forced migration to support their relatives?

During the six-month agricultural training organised by members of ACTAF in the Marne, South of Paris, participants learned bits of peasants’ history in Europe and witnessed forms of highly mecha- nised intensive farming and the pollution caused by the use of ferti- lisers and pesticides, as well as a system of entangled debts in which peasants were doomed to become workers for the agrobusiness. There was not much that could be applied back on the banks of the Senegal River, but the training enabled a longstanding network of solidary and partnership, and furnished a realistic assessment of the work and resilience that would be required to settle back in Mali.

The return wasn’t a return to an origin, to the home village of anyone in the group, but was chosen as a crossroads of migration, near a sort of ‘archaeological’ site of agricultural infrastructure that contained the historical layers that had first forced the exodus, the legacy of slavery and colonisation, and the incompleteness of independence in the countryside. The return enabled different systems of knowledge to emerge, other speculative fictions to be imagined – especially around modes of cultivation and the building of infrastructures to decolonise the technoscience fiction of development politics and farming. The experience of the cooperative to this day is a story of the creation and creolisation of farming technologies and practices within the requirements of permaculture to enable a region to sustain its ecosystems and provide people with food sovereignty, and to integrate the migration economy into the making of new futures.

Consequently, the image-making around the farming cooperative was all about escaping the persistent, paternalist, racist, colonial gaze present in the fabric of the working class, in the media coverage of the Sahel droughts or even within the ‘third world’ movement in France. It was about experimenting with forms of liberation and transmission through the making of militant photographic and moving- image works and their circulation, the production of theatre plays and communiqués, parties, screenings in the foyers, even blood drives. These contexts allowed new speculative futures to emerge. The aim of the archive project, Sowing Somankidi Coura, a Generative Archive, was first to acknowledge and recompose a ‘ciné-geography’[1], an assemblage of films, documents and cultural and militant productions that had vanished or became invisible due to the precarious conditions of their existence.

This happened to be part of a broader tendency for the digitisation of amateur and militant archives by activist groups and researchers that emerged during the 2000s in France[2] and elsewhere building up what might be termed a ‘migrant radical tradition’[3] through the constitution of a radical archive. Sowing Somankidi Coura, a Generative Archive, via a practice of collaborative filmmaking, performance, research and publishing, aims to keep the collective’s spirit alive and to engage with the stories of translation, mutations and becoming of the archives in space and time. One example is our collaboration with Kàddu Yaraax, the famous theatre company from Dakar: in 2018 we organised a two-week workshop that used elements of the archives as a point of departure, alternating with Theatre of The Oppressed exercises and other improvisations set up by Kàddu Yaraax. This resulted in Xeex Bi Du Jeex – A Luta Continua, a theatre performance and a film: both a newly generated archive in itself and a possible container for the archives, like a calabash gourd or Ursula K. Le Guin’s ‘carrier bag’.

Madjiguène Cissé (centre), spokesperson of the sans-papiers of St Ambroise and St Bernard, at a demonstration, Paris, 30 March 1996. Photo: Bouba Touré

Demonstration, Paris, 30 March 1996. Photo: Bouba Touré

Demonstration with sans-papiers from Foyer Charonne, Paris, 1992. Photo: Bouba Touré

Ibrahima Camara (left) and Fodé Moussa Diaby stand by a billboard documenting the installation and performance of the play Immigration: quelle solution? on the first anniversary of Somankidi Coura, January 1978. Photo: Bouba Touré

Exhibition marking the 40th anniversary of Somankidi Coura, January 2018

Xeex Bi Du Jeex – A Luta Continua (still), 2018, a film by Raphaël Grisey, Bouba Touré and Kàddu Yaraax

The situation in France and in Europe for refugees today is significantly worse than when Somankidi Coura was established. During the 1970s in France, it was nearing the end of the Trentes Glorieuses – the 30 years of postwar promise and expansion – and the very beginning of the repressive migration politics, but one could still fly to France or take a ferry without being arrested. During the 1990s the sans-papiers movement exposed the racial capitalism at play, and public opinion was supportive. Nowadays the precarity of refugees in France, whether at Porte de la Chapelle in Paris, in Calais, or in the administrative detention centres is worse than ever, and the refugee crisis of summer 2015 never received the same support it had in Germany, for instance.

Rural exodus and emigration to Europe hasn’t disappeared from the Senegal River, but it is now less than in regions such as Sikasso, at the border with Guinea and Ivory Coast – perhaps the result of the multiplication and consolidation of local projects that may have received support from the diaspora, such as school, farming and health-centre networks. Nonetheless the situation has been deteriorating in the region. After eight years of civil war, a military coup and the yet unclear outcome of the transition period, state governance in Mali has almost vanished. This, in addition to the absence of peace negotiations in the north and the complete failure of a French military intervention and occupation, may well cause further expansion of the civil war to other regions. The effect of COVID-19 politics got the nickname of ‘Coronafamine’ in Dakar.

The informal economy, especially in cities, turned extremely precarious from one day to the next due to lockdown restrictions. Those who have had time to worry about the virus as such are the privileged ones. The COVID-19 situation, and the expansion of zoonotic diseases globally due to forms of farming and extraction capitalism on the African continent, reinforce the need for solidarity-farming networks and a variety of artistic forms such as Somankidi Coura to bring up narratives and practices that enable the dismantling of colonial structures.

Sowing Somankidi Coura. A Generative Archive, 2017 (installation view, Archive Kabinett, Berlin, 2017)

1. Kodwo Eshun and RosGray, ‘The Militant Image: A Ciné-Geography’, Third Text, vol 25, issue 1, January 2011

2. Historical examples of such are the work done by the association Génériques (odysseo.generiques.org), and by the Agence IM’média (agence-immedia.org)

3.ThinkingofCedricJ.Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (1983)