A Carrier Bag Theory of Cinema

The opening voice-over of Carole Mansour’s documentary Stitching Palestine, written by Lebanese novelist Sahar Mandour, states after the credits: ‘Inside each of us, inside the map of Palestine, our stories were like threads that separate then come together when faced with the “knot” of occupation’. In counterpoint to the devastating homophonous double meaning – knot/not – the poetic statement sets out the film’s premise: that stories, embroidery, Palestine and resistance are one – and one, too, with cinema itself, as a mapping, narrative, visual and multi-strand medium that can carry these stories.

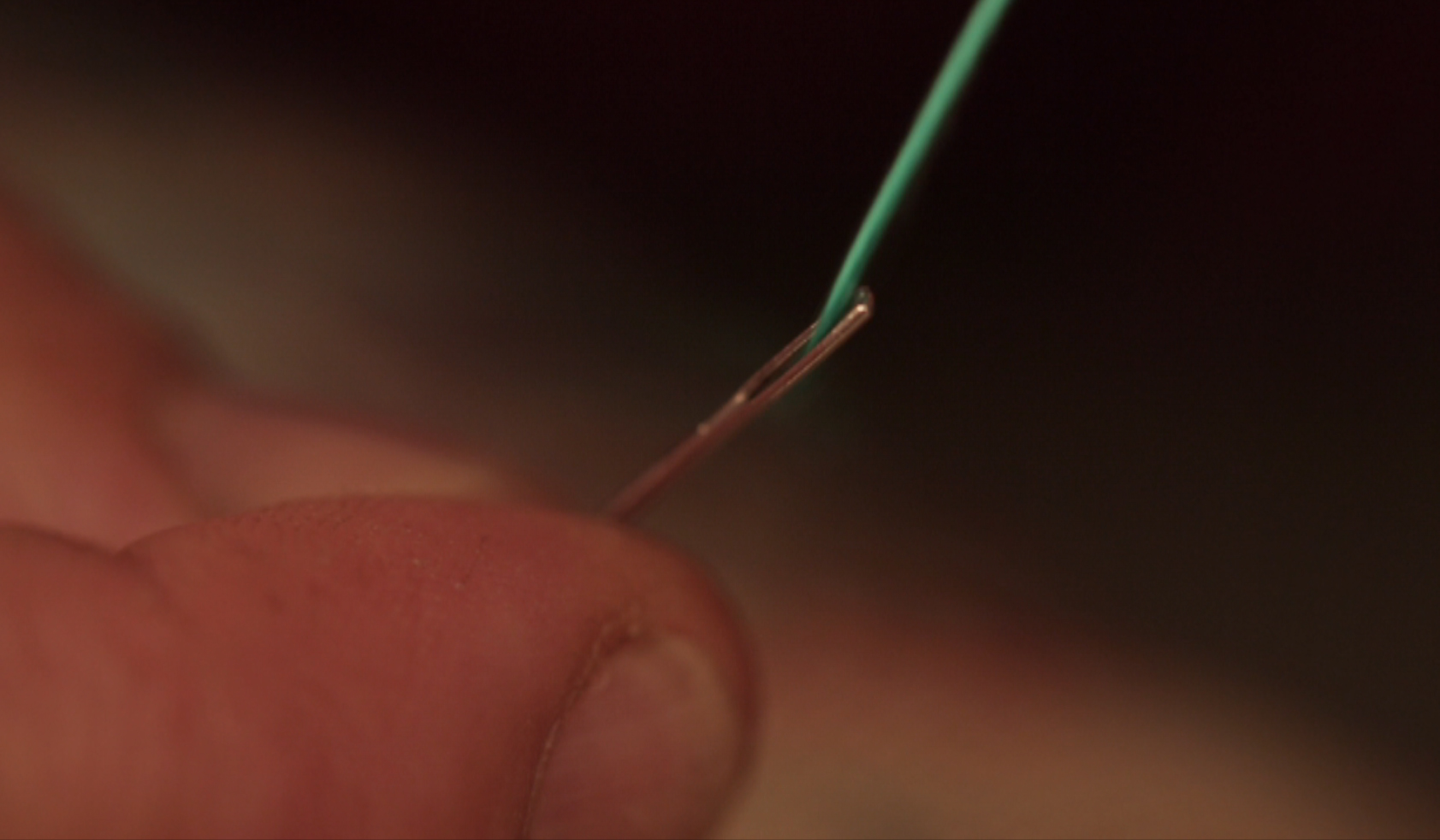

Textile art curator Rachel Dedman says, simply and powerfully, ‘tatreez – the rich Palestinian tradition of embroidery – constitutes more than heritage. Tatreez is Palestinian life. In its repetitive binding of thread to fabric, embroidery involved the very simplest of gestures, and is a practice that embodies resistance’.1 Mansour’s film shows this through repeated extreme close-ups of a thobe in process of being embroidered, from the cutting of dress fabric to the final act of removing the fine threads of the batting that enable the embroiderers to mark out their stitches with extreme precision. Mansour’s film, like her crafting subjects, shows its working, and in doing so invites us viewers to see cinema itself anew.

The repeated extreme close-ups that show us the tatreez expanding across the surface of the cloth, interfacing with the regular grid of the batting to create and yet exceed the geometric, gently give us guidance on the way to attend to the film as viewers, stitch by stitch, detail by detail. Jemma Desai speaks of this affinity for and attention to handmaking as a critical viewing strategy in her programmer’s notes on watching Yashaswini Raghunandan’s film That Cloud Never Left:

[Raghunandan] describes wanting ‘to make the film feel like a crumpled piece of paper with a wealth of stories inside of it’.

The description, less romantic than a portal, or a phantasmagoria, or a kaleidoscope, evokes for me the concept of jugaad, a Hindi term referring to the acts of creative imagination that play out in places of limited resource. The physical act of handmaking the kyakteki at scale – working the cane, the clay, cutting the plastic, wires, papers and film reels – requires multiple acts of jugaad.2

As we watch lifelong embroiderers, sisters Nazmiyeh and Jamileh Salem, work in extreme close-up it becomes clear that embroidery is not a delicate or genteel hobby: it involves precise attention to detail for nine hours a day, starting at 4 a.m, Nazmiyeh notes. Traditionally women would work for six months to produce a single thobe for a trousseau.

This kind of invisible handmaking, ‘acts of creative imagination that play out in places of limited resource’, is rarely regarded as art, and even less frequently given visibility within technological modernity except through anthropological nostalgia. In Stitching Palestine, by contrast, novelist and architectural historian Suad al-Amiry notes that traditional embroidery ‘could possibly be the earliest form of abstract art’, and its strong motifs within geometric frames are a source of inspiration for Modernisms’ refutation of naturalistic representation. Laura U. Marks makes a parallel argument in her book Enfoldment and Infinity: An Islamic Genealogy of New Media Art, where she traces the passage of what she terms aniconic art – ‘when the image shows us that what we do not see is more significant than what we do’ – from Islamic calligraphic, ceramic and textile arts into new media.3 Marks traces in fascinating detail the ways in which Turkish rugs influence fifteenth-century Venetian and seventeenth-century Dutch painting: not just as proto-colonial trade goods displayed for status, but changing the frame, perspective and figuration.4

Like translation, influence in visual culture goes both ways, rather than the unilateral dominant influence of Western figurative art as often assumed. Marks names this the ‘haptic transfer’, affirming the physical and sensory mode of influence, a movement toward density and sociality. In the film, Al-Amiry notes relatedly that tatreez is ‘like an oral story, especially in that every place has its own narrative’ – that is, that each motif is not purely iconic or static, but pictographic, condensing complex syntactical meaning, unfolding in time and space, into a single figure. As repetition and as narrative, tatreez comes into view as proto-cinema.

What does it mean to think cinema and tatreez together, not only and quite rightly as Modernisms but also as and with a winding thread of orature? Thinking about the Fates who cut the thread of life, and whose name comes from a word meaning ‘it is spoken’, Holly Pester notes in her performance essay on gossip that through…

the connection between utterance and handicraft, and the nuanced entanglement of gendered and colonised labour with unhallowed wisdoms, [t]he crafts of gossip and storytelling, the gendered cultures of speech… become entwined with labour; historically at the well, public laundries and spinning rooms; where the task of spinning yarn co-produces narratives – as well as a means of escape from the time-structures of work – converting the work-time into something other, but also embodied in the materials and apparatus of it.5

Laleh Khalili notes similarly in The Corporeal Life of Seafaring that, according to historian Marcus Rediker, ‘yarning’ as the act of telling long stories arises in English through ‘the language of seafaring developed in these sessions of ravelling and unravelling [ropes as “make-work” in the doldrums]… Like much else at sea, it developed as a way of negotiating quotidian life aboard a ship with others who do not speak one’s language’.6 Yarning as collaborative improvisation, like ‘haptic transfer’, are likewise ‘acts of creative imagination that play out in places of limited resource’, translation and cross-cultural influence from the grassroots for survival, of a kind that can only be carried in the body and memory because they rarely make into recorded documentation.

Khalili’s etymology is a useful reminder that yarning in both senses is subaltern labour that is not always gendered but always marginalised, a way of navigating a world in which one is always at sea, at the mercilessness of power. Cinema is rarely associated with either utterance or handicrafts, and is repeatedly removed from the ‘nuanced entanglement of gendered and colonised labour with unhallowed wisdoms’. Reading tatreez as orature as cinema as modernisms as haptic transfer as translation brings the labour and exploitation that undergirds industrialism, including industrial cinema, back into the frame – and adds a soundtrack of whisper and lullaby, protest song and gossip, folk tale and protest speech, running as and within the thread, inseparably.

Feminist textile historian Elizabeth Wayland Barber observed thirty years ago in her classic Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years that while it ‘is no longer possible to know most of the details of prehistoric women’s lives… among the textiles, on the other hand, we can find some of the hard evidence we need, since textiles were one of women’s primary concerns’.7 In an interview in Stitching Palestine, lawyer Mary Nizzal Batayneh extends this further, implying through her parallel narrative of her legal career and embroidery that tatreez is a form of deed in the legal sense, as well as an action: each motif is a documentary claim to a specific place and its living history and culture. To sew it is to know it. Auto-ethnography comes to fulfil a similar role in liberation movements, of staking a claim through intimate visual patterns, what writer Adania Shibli calls the ‘minor detail’ of subaltern knowledge that is overlooked and dismissed by dominance culture and thus survives in quiet urgency.8 Indigenous cultural studies scholar of Seneca descent Michelle H. Raheja termed this reclamation of ethnographic film conventions ‘visual sovereignty’, noting that this formulation:

offers up not only the possibility of engaging and deconstructing white-generated representations of indigenous people, but more broadly and importantly… intervenes in larger discussions of Native American sovereignty by locating and advocating for indigenous cultural and political power both within and outside of Western legal jurisprudence.9

Filming the doing (deed) of tatreez inscribes a further legal claim (deed) to the villages, towns, houses, groves, roads, farms, cities, and sacred spaces of Palestine, one that displaces a focus on instruments of international jurisprudence in the liberal world order. Instead, Mansour’s camera becomes a needle and the screen a textile carrying and knotting the marks and motifs of indigenous land stewardship.

Viewing is invited as in a sewing bee: as an act of collaboration that may extend into curation, further stitching the claim made by tatreez and the documentary – that of Palestinian indigeneity and land stewardship – into realisation by viewers: double-knotting the resistance. In Mansour’s hands, cinema (re)learns to be a carrier bag, that literally handy piece of wearable infrastructure proposed by Ursula K. Le Guin as a narrative (un)structure in her essay ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’ – not that fictiveness is important in the stories that Le Guin imagines being gathered in.10 Rather, she contrasts the linear, monomaniacal, rigid weaponised binarism of dominance culture’s obsession with truth/fiction objective/subjective with the generous and generative carrier bag approach of the oral storyteller who may salt her account of today’s finds with yesterday’s dreams, songs, folk tale fragments, jokes, ethics, recipes, guidance, prayer: additional and complementary realities that, like tatreez, stitch a complex set of spiritual-legal claims to lived and living land, a constant remaking of the responsibility of here-ness. In conversation with Oglála Lakȟotá musician Kite, renowned Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar, writer and artist Leanne Betasamosake Simpson notes:

I would definitely see Song as ethics and I love how integrated it is, even till this day in our community: inevitably, there will be a prayer, a song, a joke and a story. And I think that’s a beautiful embodiment of an ethical practice that is not a set of laws on paper, but it’s relational, and it’s living and it’s embodied.11

Witness the couples in Jumana Manna’s Foragers (2022) moving like living needles through brush and bush, weaving human lives reciprocally into the wild herbs that have lived with and through Palestinians for millennia. Foraging, like embroidery, is a subaltern craft, a method of mapping with the body that can only be read by those in the know. Foraging is a story just as – in Le Guin’s canny account – a story can be foraging; like tatreez, it is a legal deed, a documentation of transhistorical relationship and responsibility. Like tatreez, foraging ramifies with orality, and Manna’s film shows those arrested for and charged with foraging staging their defences in Israeli police stations, jails and courtrooms, giving them a hearing through storytelling (the film is dramatized but presented as documentary) where no hearing can usually be had. Rather than a crime, foraging becomes its own defence, evidence of the illegality of the occupation – the film is a legal document through its hybrid status as non/fiction, and simultaneously, because of that status and its foregrounding of orature, an act of healing.

Speaking about the use of matte painting and back projection rather than CGI to create the post-collapse future seen in her short film Pumzi, Wanuri Kahiu comments that the return to craft techniques was influenced by indigenous Kenyan craft: ‘We already have a tradition of tapestries and functional art and things like that, that loan a backdrop for films’.12 The film reflexively draws attention to the textile-based matte painting when the protagonist Asha wraps herself in a worn wax-printed cloth that she salvages from a dump, eventually using it to shield the maitu seed she is carrying, and then as burlap when she plants it in the sandy soil in the hope of water whose co-ordinates she has been sent in a dream.

This carrier-bag animacy, where complementary realities are vivified through hybrid documentary forms and formal strategies as in Mati Diop’s multimodal Dahomey (2024), is visible as a decolonial innovation, a new film language emerging from reclaiming and resignifying Modernisms as a transnational, resistant and anti-colonial paradigm, a riposte to colonial capitalist industrialism. Mansour’s film is a dual riposte, itself, to the conventions of writing film history: on the one hand, it is a historicised reminder of how crafts develop outwith industrial, market-driven ‘innovation’ that is engineered, in both senses; and that crafts are themselves complex technologies that merit inscription into technological histories. Conventional film history rests on the assumption encoded in the infamous scene in Nanook of the North in which Nanook (Allakariallak) is startled by a gramophone; a scene that recalls the myth of the startled Lumière spectators that has itself been debunked by Tom Gunning.13 Allakariallak was not only observing and assisting with the Flahertys’ camera set-ups on a daily basis, but lived in a contemporary home and was familiar with a gramophone.14 Regardless of that, the Inuk of Ungava Peninsula in Northern Québec had long operated their own varied and changing complex technologies, adding guns and harpoon guns to millennia of using canoes, sleds, harpoons, ice-carving tools, and echoes.

Teófila Palafox Herranz, an Ikoots basket-weaver who was the first Indigenous Mexican woman to make a film,15 rips open the opposition posited between cinema and traditional crafts, between cinema as a signifier of technological modernity and Indigenous people as objects of that technology, in her comment during a round table on the Cine de Mujer movement.

I am an artisan, I hand-weave, and I express my way of thinking in my weaving. We work with our hands like a woman filmmaker does. I can explain myself with my woven material, and in my film, I can communicate with another person. This way I express how I feel. Through a film I wanted to say everything I feel as a woman, as an organiser of other women, because I represent a group of women artisans. I also think we need to be heard, and need to communicate with other people. That impulse makes us sense how to communicate using the medium we have at hand.16

‘Using the medium we have at hand’ resonates with the claims of Third Cinema and related DIY modalities, positioning the camera and the projector alongside other forms of resistant guerrilla expression from tatreez to graffiti.

‘Animating the Present’ by Abdel Rahman Al Muzain, painted in 1979 and published as a poster by SAMED in 1985, shows two women depicted in profile: the woman in the background wears a keffiyeh that flies backwards in the breeze and long plain robe, and points a rifle towards the right, with doves emerging from its barrel; the woman in the foreground wears tatreez-embroidered thobe, headscarf and slippers, and she points a film camera in the same direction as the gun.17 Resistance is multifarious, its dynamism coming from the broad and flexible analogies between print-making, embroidery, filmmaking, and armed resistance. While the parallel of the camera and the gun goes back beyond Third Cinema and The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966), the triangulation with textiles – the cross-stitched keffiyeh in the traditional fishing-net pattern, and the symbolic and iconic cross-stitch on the hems and placket of the thobe, including a large dove bearing an olive branch just below the hip – generates an energy that is at once gendered, a feminist critique of the narrow equation of camera and gun, and crafted, aligning print-making, painting, embroidery and filmmaking as interrelated artforms and containers of resistance.

Dalloul Art Foundation director Wafa Roz notes that ‘Influenced by his mother, a trained embroiderer, Al Muzain mastered the depiction of traditional Palestinian embroidery, or tatreez, which had also become a symbol of Palestinian resistance by the 1970s… his careful brushwork suggesting the tactile qualities of stitching and couching laid across the surface of the white linen fabric’.18 While the black and white print cannot show the brushwork, the monochrome graphic print uses its black-and-white geometries to evoke the cinema; there is a similar moment in Mansour’s film where singer Amal Ziad Kaawash is photographed such that her keffiyeh looks like a film strip: textile and film come together.

Across the bottom of the poster is a slogan presumably coined by SAMED:

The Palestinian cinema

Recording the past

Animating the present

Illuminating the future

While recent feminist critics have pointed out Al-Muzayen’s frequent identification of the land of Palestine with a female body wearing the traditional, rural thobe, a potentially conservative constellation, this poster pairs tatreez not with planting olive trees, but with the cine-camera that links past, present and future. To think of tatreez as cinema is to observe that, rather than a fixed nostalgia, it encodes futurity through continuity with past and present, being a technology that enables other parallel uses of ‘the medium we have at hand’.

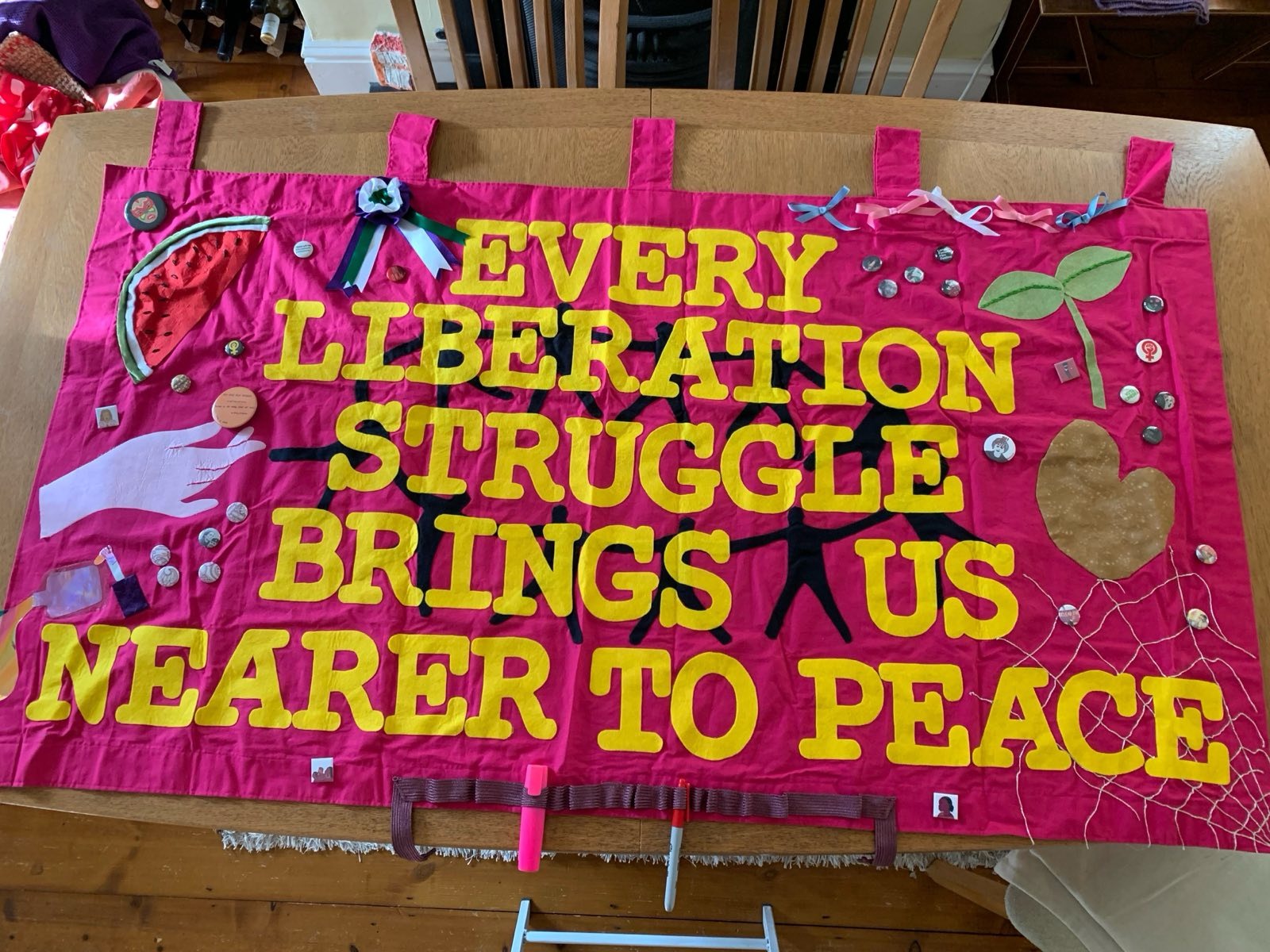

It was this seeing this poster as part of the tatreez exhibition Material Power: Palestinian Embroidery, curated by Rachel Dedman, at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge in October 2023 that inspired Club Des Femmes, the queer feminist film curation collective of which I am a member, to make our first ever cinematic banner as part of a screening programme. Club Des Femmes frequently handmake film ephemera such as zines, badges, programme notes and readers for our programmes, and in our live and digital programmes film is always part of a continuum that includes live performance, conversation, and political activism. We have been programming, writing and researching around the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp since 2014, and when we were invited to be part of Tate Britain’s ‘Women in Revolt’ exhibition in 2024, we wanted to echo and expand the exhibition’s own ‘Greenham room’ with attention to the continuity of feminist anti-war, anti-colonial and anti-nuclear activism and filmmaking.

CDF collective member and textile historian Jenny Clarke’s banner ‘every liberation struggle brings us nearer to peace’ (2024) features three motifs that relate centrally to the programme’s focus on Greenham Common, all of which combine in Tina Keane’s single-channel video and twelve-monitor installation, In Our Hands, Greenham (1982–84). The outstretched hand on the left of the banner recalls that the images Keane shot at Greenham are vignetted within the framing hands of Keane’s colleague Sandra Lahire, through Chroma Key superimposition; two of those images are the famous circle dance on the base itself (evoked by the silhouette figures linking arms in a circle), involving protestors breaking in through barbed wire, that took place on New Year’s Day 1983, a ritual that itself evoked the huge Embrace the Base protest a few weeks earlier, one of the largest-scale protests ever to take place in the British Isles; and the spider web in the bottom right corner that is repeated in Keane’s video and became, in Greenham women’s art, an image of ecological resilience, interspecies connectedness, feminist DIY story-telling and art-making. As spinning, the spider’s webwork relates reflexively to banner-making as a craft practice at once labour-political and feminist that was prevalent at Greenham, drawing simultaneously on the supposedly domestic labour of embroidery and the long history of union and association banners carried in marches. The programme title and banner phrase was found by CDF member and feminist curation historian Selina Robertson on a 1984 photograph in the Rio Cinema Archive, capturing signs at the Hackney Women’s Peace Camp in front of Hackney Town Hall.19

A banner is at once iconic and representational, and a moving challenge to narrow definitions, linear narratives, and the policing of meaning. We were aware that we were hanging a banner in Tate Britain in the middle of ongoing court cases in the UK against pro-Palestine marchers who had featured iconic emoji of parachutists and coconuts on protest signs; that is, in a moment in which DIY punk political protest strategies of salvage and repurposing as critical speech were under threat of being criminalised. While the banner evokes Greenham, it includes iconic images of a watermelon slice and a green shoot in solidarity with Palestine and pro-Palestine protestors, making a case (as we did in our November 2023 newsletter), for ‘solidarity with generations of feminist activists for peace and against colonialism, militarism and the arms trade, stretching back to the international protest of Greenham Common and beyond. We continue the tradition of Women in Revolt by supporting screenings and actions for Gaza and Palestine’.20

Appliqued banners are unusual presences in film spaces, and even in visual art galleries, where they are rarely hung as art, perceived instead as both crafted and politicised. By hanging our banner at Tate Britain, even for one evening, Club Des Femmes joined a line of feminist artists and art historians who have contested that exclusion from visual art – and made explicit the linkage between feminist experimental cinema and other forms of creative practice for resistance: and specifically how embroidery and textile arts as moving and mobile screens carry a history of direct opposition to militarism and occupation.

This sets up an uncanny echo with a niche thread of sewing in film theory and history: film theorists Jean-Pierre Oudart and Daniel Dayan borrow from psychoanalyst Jacques-Alain Miller the term ‘suture’, which he uses briefly to refer to ‘the relationship which enables the subject to be represented by a signifier’.21 For Oudart, this offers an explanation for film viewing’s soothing, all-encompassing and absorbing fantasy space, with the viewer ‘sutured’ by conventional Hollywood editing into the diegesis as the child self is ‘sutured’ with the mirror reflection in order to enter signification. For feminist filmmakers, this term became a site for intervening into early psychoanalytic film theory, which positioned a universal white, straight, cis male viewer as a universal term. In Annabel Nicolson’s Expanded Cinema performance Reel Time from 1973, a sewing machine stitched a long loop of black-and-white film that then ran through a 16mm projector. The classed and gendered history of the sweated clothes trade and piecework shapes two crucial UK feminist films of the 1970s, documentary The Song of the Shirt (Sue Clayton and Jonathan Curling, 1979) and experimental film Thriller (Sally Potter, 1979), themselves stitched together by having scores by composer and bassoonist Lindsay Cooper.22

Feminist filmmakers pick up the dropped stitch of psychoanalytic film theory – and in doing so, an artisan filmmaking re-emerges with a feminist materialist labour politics, a craft of make-do-and-mend, kitchen table compilation. This valuable, if short-lived, intervention insisted on an embodied cinema emerging from long histories of making with the medium at hand, by hand. At the same time, it obscured the original term that inspired the intervention. Miller borrowed ‘suture’ from psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, who had an abiding fascination with Surrealism, and its association with Lautréamont’s famous image of modernity’s juxtapositions: the marriage of an umbrella and a sewing machine upon the dissecting-table. But it is the dissecting-table rather than the sewing machine that underlies Lacan’s suture: he trained as a medical doctor before qualifying as a psychiatrist. His only known period of medical practice was at Val-de-Grace military hospital in Paris during the Nazi occupation. Lacan’s sutures were military medicine, stitches administered to bodies that had both experienced and dispensed violence.

Dominant histories of cinema narrate it through and as progressivism: scientific experiment, technological innovation and market expansion. They often omit three far more violent origin stories: firstly, the Lumières’ status as factory owners surveilling their own workers and selling the images of their labour back to them like proto-Musks; secondly, what Fatima Tobing Rony calls, in The Third Eye, the ‘fascinating cannibalism’ of early silent attractions’ picture-postcard consumption and marketisation of colonised lands and peoples, which begins with the Lumières’ Train Station in Jerusalem, filmed in Ottoman Palestine in 1896, just a few months after their infamous first Paris screening in 1895; and thirdly, a battlefield in the American Civil War where a field medic noted that the oily, flammable substance in guncotton not only acts as an incendiary for rifles, but when it falls on the skin, forms a fine, flexible shield that can cover and heal wounds: a film, a second skin that offers healing. Cinema, from the start, is a pharmakon: a poison that can kill; and a medicine that can heal. It is a weapon that wounds and a wound covering. It is military technology and guerrilla improvisation. It is implicated in the industrial capitalism of the American North and in the struggle to end slavery. It is metallurgic extractivism and it is intimate fabric. It is the suture that holds together the paradoxes of late capitalism, an impossible tension.

In his dossier on suture, Stephen Heath notes that Chantal Akerman’s News From Home (1976) refuses suture as a patriarchal strategy of containment that is also one of erasure.23 Akerman’s refusal takes place through a counter-cinematic combination of long takes of New York with voice-overs reading letters to the filmmaker from her mother, a strategy that will be picked up by Mona Hatoum in her exilic film Measures of Distance (1988), in which the Arabic script of the artist’s letters to her mother is layered into the moving image.24 To refuse psychoanalytic suture is to refuse fictionalisation, to refuse to become an imaginary object for others to think with; Lacan defined the term as the ‘junction of the imaginary and the symbolic’, the site of lack. In this context, Heath connects suture to psychoanalytic resistance – a term that feminist counter-cinema will politicise. Stitching Palestine places the needle back in the hands of textile workers who press it against the resistance of the fabric to make their own cinema whose symbolic logic redefines how we see – and how we are asked to carry those images with us. Marks comments that ‘Contemporary art is aniconic when it consists of carrying out ideas and creating social interactions. These are not especially perceptible forms of expression: the image is the trace, effect, or document’– additionally, we could add, the carrier bag that both contains and shapes the social interactions and actions that come from carrying, collectively.25

Both translation and metaphor stem, at root, from the classical Greek verb meaning ‘to carry’ (pherein): to carry across. Tatreez and cinema figure each other as both translation and metaphor: that which carries across, carries between, freighted with more than meets the eye, with the underside of handmaking labour and the knots of historical resistance. Tatreez, finally, reminds us that cinema does not stop on the screen: like a thobe or a basket, it is portable, wearable, intimate. The carrier bag theory of cinema means we cannot let go of resistance, or leave the work on the screen – it is part of us, stitched and gathered in.

Endnotes:

- Rachel Dedman, Stitching the Intifada: Embroidery and Resistance in Palestine (Common Threads, 2024), 5.

- Jemma Desai, ‘Through the Kyatketi’, Alchemy Film & Arts, October 2020, https://alchemyfilmandarts.org.uk/continue-watching-that-cloud-never-left/

- Laura U. Marks, Enfoldment and Infinity: An Islamic Genealogy of New Media Art (MIT, 2010), 5.

- Marks, Enfoldment and Infinity, 85–87.

- Holly Pester, ‘A Charm of Powerful Trouble’, in Bodies of Sound, eds. Irene Revell and Sarah Shin (Silver, 2024), 144.

- Laleh Khalili, The Corporeal Life of Seafaring (MACK, 2024), 41.

- Elizabeth Wayland Barber, Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years: Women, Cloth and Society in Early Times (WW Norton, 1996), 23.

- Adania Shibli, Minor Detail, translated by Elisabeth Jacquette (Fitzcarraldo, 2022). In conversation about the book with Professor Nora Parr at Burley Fisher Books in October 2024, Shibli picked up on Parr’s question about a particular ‘minor detail’, the role of the spider in the first part of the novel – the only element that does not have an echo or repeated reference in the second part. Shibli described spending a long time watching a spider spin its net (her choice of words) during the early phase of writing the book, when she was living close to the bookstore in Hackney, and related her use of the spider, along with the book’s canine characters, to the significant animal presences in the work of atheist, pacifist, vegan medieval Arabic poet Abū al-ʿAlāʾAḥmad ibn ʿAbd Allāh al-Maʿarrī, known as al-Ma‘arrī.

- Michelle H. Raheja, ‘Reading Nanook’s Smile: Visual Sovereignty, Indigenous Revisions of Ethnography, and Atanarjuat (The Fast Runner)’, American Quarterly 59.4 (2007), p. 1161.

- Ursula K. Le Guin, ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’, was written in 1986, first published in Denise M. Dy Pont, ed., Women of Vision (St. Martin’s Press, 1988), collected in Le Guin, Dancing on the Edge of the World (Gollancz, 1989), 165-171, and reprinted in Le Guin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (Ignota, 2019), 25-40.

- Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and Kite, ‘In Conversation’, in Bodies of Sound, 191.

- Wanuri Kahiu, quoted in Brendan Seibel, ‘Kenyan sci-fi short Pumzi hits Sundance with dystopia’, Wired, 22 January 2010, http://www.wired.com/2010/01/pumzi/

- Tom Gunning, ‘The Cinema of Attraction[s]: Early Film, The Spectator, and the Avant Garde’, in The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded, ed. Wanda Strauven (Amsterdam University Press, 2006), 381–388.

- Jules Caldera, ‘A Century in Cinema: Nanook of the North’, Film Inquiry, 2 September 2022, https://www.filminquiry.com/a-century-in-cinema-nanook-of/

- Art of the Commune, ‘Teófila, armed with courage, the first Indigenous woman film-maker in Mexico’, Chiapas Support Committee, 25 March 2021, https://chiapas-support.org/2021/03/25/teofila-armed-with-courage-the-first-indigenous-woman-film-maker-in-mexico/

- quoted in Annemarie Meier, ‘Cine de mujer. Individualismo y colectividad’, in Miradas de Mujer: Encuentro de cineastas y videoastas mexicanas y chicanas, eds. Norma Iglesias and Rosa Linda Fregoso (El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & University of California, 1998), 77; translated by Mar Diestro-D’opido and reprinted in Lo personal es politico: feminismo y documental, eds. So Mayer and Elena Oroz (INAAC, 2011), 108

- https://www.palestineposterproject.org/poster/animating-the-present

- Wafa Roz, ‘Bio’, Abdelrahman Al Muzayen artist page, Dalloul Art Foundation, https://dafbeirut.org/en/abdelrahman-al-muzayen

- Photograph available at: https://www.clubdesfemmes.com/events/cdf-x-women-in-revolt-tate-britain-21-feb-every-liberation-struggle-brings-us-nearer-to-peace/; Hackney Women’s Peace Camp: https://museum-collection.hackney.gov.uk/names/AUTH5763.

- Club Des Femmes, ‘Femmes du Monde’ newsletter archive, 8 November 2023, https://us9.campaign-archive.com/?u=1d272f20c8dc96484cf99fd3d&id=6806c9bce4

- Jacques-Alain Miller, ‘A and a in Clinical Structures’, in ‘Acts of the Paris-New York Psychoanalytic Workshop, 1988’, reposted on The Symptom, nd, https://www.lacan.com/symptom6_articles/miller.html

- Filmmaker Sue Clayton has provided online access to The Song of the Shirt via Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YZJMb0vSdFM; Thriller can be rented or bought on Vimeo On Demand: https://vimeo.com/store/ondemand/buy/86583?popup=true&r=.

- Fatima Tobing Rony, The Third Eye: Race, Cinema, and Ethnographic Spectacle (Duke University Press, 1996), 9.

- Stephen Heath, ‘Notes on Suture’, originally published Screen 18 (Winter 1978), reposted on The Symptom, nd, https://www.lacan.com/symptom8_articles/heath8.html

- Jacques Lacan, Le Séminaire, livre XI: Quatre concepts fondamentaux de la psychanalyse (Paris 1973), 107, quoted Heath, ‘Notes on Suture’.

- Marks, Enfoldment and Infinity, 5

So Mayer is a writer, publisher, bookseller, organiser and film curator. Their first collection of short stories Truth and Dare is out now from Cipher Press, and was long listed for the 2024 Republic of Consciousness Prize. Their recent books include A Nazi Word for a Nazi Thing, a book-length essay on queer films, bodies and fascism for Peninsula Press, and their most recent collaborative projects are Space Crone by Ursula K. Le Guin (Silver Press), The Film We Can’t See (BBC Sounds), Unreal Sex (Cipher Press), and Mothers of Invention: Film, Media and Caregiving Labor. So works with Silver Press, Burley Fisher Books and queer feminist film curation collective Club Des Femme