Descola / Unschool

According to the anthropology of Amazonian peoples, beings in their multiple forms – humans, plants, rain, thunder, objects or minerals – have their own characteristics and ways of seeing and being seen. The human is only one more member of a web of relations and not the privileged point of view over other beings. In this sense, every perspective is made from a body: to see is to be somewhere.

“The camera is the body” is a collaborative project that aims to question the centrality of human vision – the privileged sense of our sensitive apparatus – through experimental cinematographic experiences and devices that incite and work our multiple senses: touch, hearing, intuition, other ways of seeing, hearing, guiding and being guided. Here cinema is not a form to be reproduced, but to be (re)invented. What do we see? Who sees? What is seen? With whom do we see? What other sensitive potencies do we want to cultivate beyond vision?

“The camera is the body” is also a practice and philosophy that grounds a multitude of interactions and forms in my work in cinema, writing and critical pedagogy. In this case, during one school year, the project accompanied a group of high school students at High School Dom Dinis (Chelas, Lisbon) through film screenings, debates, free forms of interpretation, sensory activities and the production of the collaborative film “13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” (2020), screened at Open City Documentary Film Festival in 2021. The pamphlet and interview presented below in a printed trace of our collaborative project and includes an interview made by students Vera Amaral and Mário Neto about our collaboration.

– Ana Vaz

Interview

Dom Dinis School, Marvila, Lisbon, 2020

M: Hey Ana, now that we’ve reached the end of the workshops, here are our questions for you. To start with, what was your vision for the initial project?

A: It’s funny to talk about “vision”, since this was the word that our whole year’s work was mostly focused upon. Actually, my “vision” was quite different from what we ended up doing. To start with, the project was based on the concept: “the camera is the body”. My idea was to think about how we could, as a group, imagine a new camera or a new way of filming based on, and through, the body, from corporeal, sensory experiences. I’d suggested to the school that we should create a partnership between the multimedia and robotics departments, so that we could co-create some kind of device that would help us explore the relationship between the camera and the body.

However, I started to realise through our workshops that it wasn’t optics in the technical sense that interested us, but rather a way of looking, being, and living in the world… Basically, a critical and collective philosophy on the gaze. I remember when I said: “It doesn’t have to be a new camera, it can be another way of filming”, I saw everyone breathe a sigh of relief. So, it seemed very natural to me to abandon the initial idea and explore this other abstract, unfamiliar, and delicate direction that we have been very slowly getting to grips with over the last few months.

M: You’re right, it was a natural change. After this change, do you think the project has met your expectations? Like, is it going in a good direction?

A: It’s strange talking about expectations, since, very often, expectations have a tendency to create authoritarian attitudes, with no room for transformations or surprises. What happens is that the reality always ends up being more powerful than our desire. If I really wanted to meet my expectations, I might have been frustrated when we decided to abandon the initial project. But bearing in mind our project’s philosophy, I’d say that this type of attitude would be the exact opposite of what we were aiming for. We spent a good part of the year talking about all the problems linked to the violence of a certain kind of human society — western, rational, colonising — that always seeks to domesticate, tame, control what they call “nature”. If I wanted to make a project that was only about my own expectations, I would be, in a certain sense, reproducing what we’ve been trying to challenge.

However, I never imagined that we would reach July 2020 in the middle of a worldwide pandemic, which stopped us from continuing our face-to-face workshops, which forced us to work remotely and make cinema over Skype – something completely antithetical to my desire to work with cinema as a corporeal and in-person artform. I think it was an unexpected year for all of us, but these challenges also strengthened our collaboration.

M: I think the quarantine might have helped a bit, it gave us more ideas, we looked at things differently.

A: Do you think so?

M: Yes, I think so. Do you think it helped or hindered the situation? Did it change something or nothing at all?

A: I think you’re right, that there was a certain degree of focus when quarantine began. As we’ve discussed several times, many people were not even able to quarantine: the “invisible” workers who continued to work, people who live on the streets, all the inequalities of the world we live in became even more blatant. But for us, those who had the “privilege” of being able to quarantine, it is as if this sort of suspension of “normal” activities, this moment of pause, also gave us a degree of concentration and an awareness. And I feel that for us, the few of us who persisted with the project, it was as if suddenly the ideas that we were working on in a very abstract and conceptual way became very concrete.

I remember the moment when you, Mário, said in the video you made: “Yeah, but the world goes on, right?” Actually, for one part of the human species things “stopped”, but we humans do not live alone in the world. We spent the whole year talking about this, about this separation between nature and culture, between humanity and the world. And suddenly the pandemic reminded us that we’re not really alone, that we contaminate one another, infect each other and live together. So yes, I think there was an interesting turning point at that moment.

M: So… did you like working with us?

A: How could I not? Maybe the word ‘like’ isn’t strong enough, considering all the hurdles and learning processes that we faced together. I think that the effort it takes to build anything is never just for fun, is it? It’s also a challenge, a hurdle to overcome, so I feel that much of this joy that we ended up feeling was also the fruit of mistakes, frustrations, of moments of uncertainty that made this joy grow into something bigger. In other words, we not only learned to see each other in a different way, more intense and sincere, but also to share a critical way of thinking and vocabulary, a collective attitude that after a year of work we now recognise. And I think this is beautiful, because it’s something I can’t teach you: it’s not a book you will read, nor a test you will pass. It is a slightly more intuitive understanding of what we went through, which… which is beautiful. It’s joyful and unexpected, I think that is also the beauty of the project.

M: It’s true that we grew a lot during the project.

A: Did you feel so as well?

M: Absolutely.

A: What do you feel changed?

M: Practically everything: our ideas, perspective, our vision of things. Even more so with the situation that we are living through. Everything helped my development. Did you feel the same thing?

A: Yes, I think that it was a challenging year with a lot of growth, in many ways, not only because of the pandemic being this final big turning point in our lives. But also, because our coexistence intensified and transformed my perception of the city of Lisbon, by meeting people I would never have met if it wasn’t for this experience. And this was very impactful, meeting you, the school, the neighbourhood.

M: Now moving on a little, how would you describe the film we made? I mean, we can’t say exactly because we haven’t finished it yet, but from what we’ve shot and produced so far.

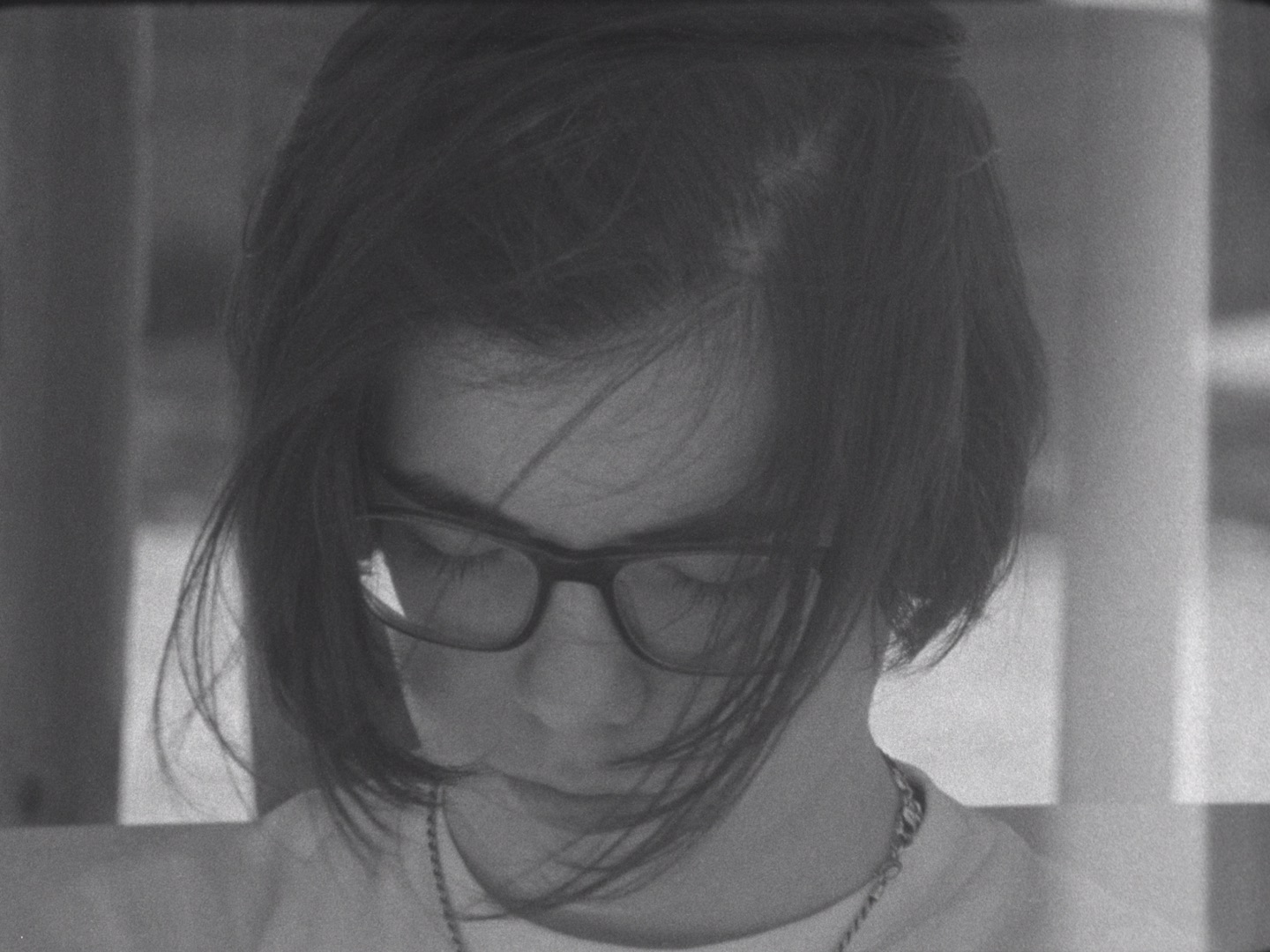

A: Like you said, it’s difficult to describe, but the word that most comes to mind is: groping. And groping in a sort of darkness. We’ve just finished a semester since filming and now, at the beginning of editing, I see myself again in these sensory exercises we did at the beginning of the year: walking with my eyes closed. I feel like I don’t have any control over the film, it is the fruit of energies and contributions that come from you and also from Paula [Nascimento], who was with us throughout most of the process. What I am sure of is that it is the fruit of a process that I would call, not without humour, positive contamination, between the diverse worlds that were shared here: the intuitions, sensibilities and reflections of Mário, Vera and Paula. I still don’t know what it will be like, but I am beginning to have a sense of what it might be. And the only thing that comes to mind is an idea of an imaginary and ephemeral community. The portrait of exchanges that have happened: corporeal, lived, uniting ways of seeing and very specific experiences. It is a film that I could never have made alone, that’s for sure.

M: It’s the collective.

A: That’s it, this ephemeral body that has traces of us all. What about you, what do you think? How would you describe the film before it exists?

M: I think that the film can be everything, it can be many things, but it can also be nothing. Because it’s still very rough, it still needs polishing when it comes to… – what do you call it? – the editing. We’ll try to help, with some sequence, image or even audio, and we’ll see. But I’m very happy with what we’ve achieved so far. I think the film will be very interesting to watch. And to listen to as well.

A: Vera?

V: I agree. I don’t know, I think… It’s like Ana was saying, that there’s a bit of all of us in the material and everything we’ve done so far. And I think in the end it’s going to basically be just that: a collective of experiences and what we’ve shared throughout this year. And I’m also very happy about what we’ve achieved so far.

M: So, I think that’s it. It’s been a pleasure to working with you.

A: It’s been a pleasure working with you as well. Thank you for the interview and the questions, thank you for your persistence, for staying to the end. Like the teacher who came in here and joked, “Oh, you’re the resilient ones!”. And you really are. I really believe that, I think that word resistance is of great significance for us today, in this world in flames. We need to be resistant, not a blind resistance, but a resistance that seeks sensitivity and understanding, that seeks an awareness of how to inhabit the world – a re-existence perhaps.

Translated by Katy Carroll

High School Dom Dinis (Chelas, Lisbon) was created in 1971 and soon became a role model for public schooling in Portugal due to the way it responded to its social-cultural context with innovative schooling methods. To this day, the school continues to affirm itself as an articulated space capable of responding to contemporary teaching-learning models and current parameters of environmental quality and energy science. The school is recognised for its robotic and multimedia department allowing students to experiment with media and technology is sustained and focused ways. The socio-economic context of the school community is heterogeneous, welcoming the population of Chelas, Bela Vista and Olivais.

Vera Amaral (2002, Lisbon) is a student at the Escola Secundária Dom Dinis in Marvila.

Mário Neto (2001, Aparecida de Goiânia, Brazil) is a student at the Escola Secundária Dom Dinis in Marvila.

Paula Nascimento programmed the three editions of the Africa Festival (2005, 2006 and 2007) for the Lisbon Festivities, an event which brought a different attitude and vision of the music produced in Africa or with links to the continent. She was part of the Africa.cont team and, since 2016, she has been collaborating with EGEAC (a public organisation responsible for managing cultural actives in Lisbon), in the realisation of visual arts exhibitions and the production of music and performance in the context of their exhibitions. Paula intensely lives her Lisbon and the changes in cultural life recognising the marks of time in the streets and in people’s mentalities. Angola and Cape Verde are living histories of her family. Paula persists in the struggle to understand the world and to change the narrow vision of a culturally complex continent.

Sound artist, graphic designer and publisher, the work of Nuno da Luz (Lisbon, 1984) circumscribes both the aural and the visual, oscillating between the sonic exploration of places – in the form of performances and sound installations – and the production of books – through the publishing house ATLAS Projectos (in collaboration with Gonçalo Sena).

Ana Vaz is an artist and filmmaker born in the Brazilian highlands inhabited by the ghosts buried by its modernist capital: Brasília. Originally from the cerrado and wonderer by choice, Ana has lived in the arid lands of central Brazil and southern Australia, in the mangroves of northern France and in the northeastern shores of the Atlantic. Her filmography activates and questions cinema as an art of the (in)visible and instrument capable of dehumanising the human, expanding its connections with forms of life — other than human or spectral. Consequences or expansion of her cinematography, her activities are also embodied in writing, critical pedagogy, installations or collective walks.