Saeed Taji Farouky on The Land of Common Disgrace

By Eleanor Lu and Lydia de Matos

FILMING IN PROGRESS––BY ENTERING YOU CONSENT TO BE A PART OF THIS DOCUMENTARY PROJECT

Printed on a sheet of A4 and affixed to the window, these are the words that greet you at the Fishtank Workshop. A few feet away, on the pavement, a small chalkboard affirms ‘OPEN TO ALL!’

A film set is usually a controlled environment, but here that control has been surrendered. In the middle of the small studio sits a plywood structure, a witness stand that was built the day before. Around it, the usual suspects: camera, lighting and sound departments. But there’s a crowd of observers too: a makeshift jury for the makeshift courtroom.

Perched on chairs or sitting cross-legged on the floor, we chat, share food, share stories: the difference between friends and strangers is, at moments, barely perceptible. We might not be members of the crew, but somehow each of us has become a component of the set: ducking out of the way of a boom pole, making room for a change of camera angle, passing equipment along until it reaches the person who needs it.

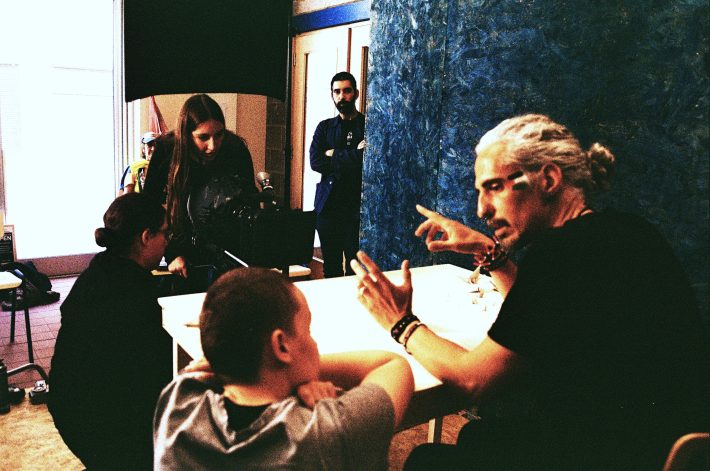

Then a call goes out for quiet on set and the chatting turns to anticipation. We may not appear in the frame, but our presence feels as necessary as those speaking to the camera. We are here to bear witness. Each person who sits in front of the camera is an activist who has been arrested for taking part in pro-Palestinian protests. Over the six days of Open City 2025, these activists, alongside the project’s crew and members of the public, built recreations of the rooms in which they were detained and questioned by the state. Watched by the small audience of passersby, festival goers, and friends, they presented versions of those moments. Part re-enactment, part re-imagination, the scenes evolved in real time. Details from the interviews were altered to subvert moments of powerlessness. The project’s director, Saeed Taji Farouky, read opposite the activists, playing the part of police officer or judge, engaging in a back and forth with them between takes to adjust the dialogue. By the end of the week, the sets had been torn down; the Fishtank Workshop became an empty room again. In around a year’s time, The Land of Common Disgrace will be a finished film, but over the course of Open City 2025, it was a theatrical, participatory, collective act of resistance and education.

Farouky’s practice spans filmmaking, journalism, education, and curation, always with an eye to radical, ethically conscious, alternative forms of storytelling. We sat down with him to discuss his most formally divergent work yet.

Lydia de Matos: Usually at a film festival, filmmakers present finished works, and the festival is a moment of transition, a handing over of the film from the filmmaker to its audience. With The Land of Common Disgrace, you upend that relationship. What’s on show isn’t a finished work; it’s not even a work-in-progress, in the traditional sense of an unfinished object. It’s the process itself. How did that come about?

Saeed Taji Farouky: Last year I programmed a few events for Open City. There were some screenings and discussions, but there were also three participatory events. One of them was an extension of this militant karaoke that I’m experimenting with, Kanafani Karaoke; the second was an invitation for people to tell the story of a film they were never able to make because of the occupation, and the third was a performance lecture related to architectures of occupation and my grandfather. And those, for me, were more exciting [than the screenings], because I’m very inspired by Third Cinema, and the idea of making and exhibiting cinema as a political act. How can you recreate the circumstances of, say, Latin American Third Cinema, where just meeting to watch The Hour of the Furnaces was a subversive act because it was illegal? And then, on top of that, you are talking to people around you about how to develop better strategies for resistance, so the film itself becomes an act of resistance and about building better strategies. I’ve always wanted to figure out how to extend that into the present. But we live in a very different world. The Hour of the Furnaces is over four hours long, and they would continually stop it and have discussions. The whole event was a lot longer. We don’t really have that capacity to do that. We’re also not in the middle of a revolution, as they were then.

But there are ways to do it that I think are more complementary to the material conditions we’re living with now, particularly with regards to Palestine, which is always my focus: the material conditions in Palestine, but also the material relationship between the British state and the genocide in Palestine. So the first thing I did was to bring together a bunch of my friends who work in theatre, including experimental theatre, to ask: what kind of event can we do around a film that would activate people in that way? I was thinking of something like, for example, Zineb Sedira’s exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery, where she recreated one of the rooms from [Gillo Pontecorvo’s] The Battle of Algiers. I love the idea of building together. I love the idea of bringing an element from cinema out into the real world, where people can meet and organise. So we had this whole conversation where we came up with principles that the project would fulfill. Then I thought, okay, now I have to find the film that this outreach programme will work with.

The second layer came when I had to appeal my conviction for chaining myself to the front of an Israeli weapons company. And it was terrible; my barrister said it was one of the worst trials they’d ever seen, because I was constantly interrupted by the judge and the prosecutor. I was stopped from saying anything about the political context, the history of Palestine, even mentioning my own family. The judge said, ‘This is not a political forum,’ which I found also really offensive, because, in essence, she was saying, ‘Your family history is now politics and it belongs in another realm’. And what bothers me most is that I just acquiesced. When the judge told me to stop talking, I complied. I obsessively replayed those moments for weeks after; I couldn’t sleep and I couldn’t think straight. I was embarrassed. And the only way I could find to escape the shame was to imagine a different version of the trial. Because I’m a filmmaker, I play out scenes in my head all the time: so the judge said what she said, and then I would confront the judge, and it was very cinematic. It was almost like the climax of a courtroom drama: the judge is shocked, and the viewers stand up and clap, and I emerge a hero. That was how I liberated myself from this thing that was really oppressive in every way. It was a way of dealing with my own embarrassment, because I think of myself as quite radical, but the moment the state said to me to stop talking, I stopped talking.

I thought, what if we invite other people in on the act of imagining a better outcome for these trials?

LM: While the project is going on, you have a rotating audience. Did you have a particular idea of how they were going to interact with what you were doing? And did that end up being reality

SF: Honestly, I could not have dreamed of a better outcome. It was exactly what we all wanted from the whole thing, which is incredible. For me, I think the priority was to produce a kind of moment of liberation for the participants, which worked incredibly well. We did workshops with them so that they would get to know each other and be more comfortable. Some of them, like me, had this burning regret of either having said something or not having said something, or not having done something. And they were able to escape from that obsessive cycle.

The fact that it’s performed in public means that they are presenting this act of defiance to other people. That was also important. I don’t focus on the idea of individual ‘heroism’ for activists today. That’s not my priority. But I do think when you have doubt or fear, or when the conditions are just extremely soul-destroying, a sense of heroism helps keep you going. I don’t think it should be an individual’s motivation for taking action. We should disrupt the weapons supply chain because we have to end the genocide. But, occasionally, I need to feel good about myself, otherwise I wouldn’t carry on. You need people to look at you and say, ‘You’re a hero,’ and then, of course, you get embarrassed, and you say, ‘No, I’m not.’ But you take that home with you, and I think it’s important.

It was also important to me that the process that the state wants to hide be brought out into the open because, for many of the participants, the case was either thrown out or all charges were dropped. Some of them have taken out lawsuits against the police for unlawful arrest. Even listening to the charges, the level of absurdity is, on the one hand, shocking and, on the other hand, just hilarious. You realise this is just the demand to quash any kind of show of support for a liberated Palestine, and any kind of opposition to government policy. And because of the information we have from the inside, through the participants and their lawyers, you start to see that these are not isolated incidents. But the language that the state uses to portray people in a particular way, the use of terms like ‘violence’ or ‘terrorism’, the way the state has manipulated the meaning of those terms… I think it’s vital for the public to witness this, because this is how, brick by brick, the fundamentals of democracy in this country, the fundamentals of a free press, are taken apart.

One of the participants is a documentary filmmaker who was arrested for filming. I was arrested for filming. During the protest, paint was sprayed on a building, and they managed to characterise this, legally define this, as violence. These are things that make absolutely no logical sense. But for the state to construct a case, all of these things have to fit together. And then the rest of society and the rest of the judicial system has to acquiesce to this new definition of violence, or terrorism, which includes sabotaging Israeli weapons manufacturers, or a new definition of racism, where the state will portray this as an attack on a Jewish business, whereas that had absolutely nothing to do with it. So the project is also an attempt to blow the doors open on what is otherwise a secretive process.

The final aim is to get people together meeting and talking. I don’t know how successful it was for those observing, but, to me, it looked exactly how we wanted. It created its own little ecosystem, where someone would show up one day out of curiosity, become friends with one of the activists, and then come and build with us the next day. And they would leave with a different perspective. It could be that they learned something, that they’re inspired to take action themselves, that they have a different respect for people they otherwise thought to be criminals. Or it could be as simple as having learned how to use a drill. That’s useful, that’s a skill. It was also about creating these networks. If there’s another emergency, suddenly those people might be willing to stand at the barricades with their comrades. That takes time. That’s more than just organising: that’s about trust, about love. Being in a room with someone, building something, laughing, making mistakes – that’s how you build love and trust. There’s a lot more to it than just the practicalities of how many people you can get out on the streets on any given day. No, it’s: if I see you in trouble, do I love you enough to put my life at risk to save you? That’s what we need to know today.

Photograph by Charles Kristofferson

LM: Back to the idea of manipulation that you brought up… Coming to watch for a while, I noticed interruptions, both on the part of the judge or barrister, and technical interruptions when, for example, microphones stopped working. You just mentioned being interrupted while in court, and the way that it almost forced acquiescence. In retrospect, the interruptions in the performance feel like a microcosm of that larger manipulation. Was that purposeful?

SF: Normally, the judge will do everything they can to allow every person to give their testimony unbroken. For example, testimonies should not be scheduled 15 minutes before lunch break. They genuinely want to give people continuity. It’s also because the art of being a barrister is forming a narrative, especially in a protest case where it’s all about belief. It’s not really about establishing facts, it’s about my beliefs. My narrative is that my grandfather was disenfranchised, his land stolen, and he was sent into exile. He was also arrested for resistance against the British occupation of Palestine. And then our family home was turned into the Israel Institute for Biological Research, which is the centre of biological and chemical weapon development in the country. There’s a very clear continuity between my family history and me taking action. So, by law and by morality, I should be allowed to establish that continuity. I wasn’t. The courts usually break at four and the judge decided to begin my testimony at about quarter past three, knowing that it would not be finished by four, so she intentionally disallowed me from having a continuous testimony. Then the added manipulation from her was that I wasn’t allowed to speak to my solicitor. Normally, in a trial, at every stage, you’re talking to a solicitor asking, is this working? What new strategy can we try? But I wasn’t allowed to speak to my solicitor for 12 hours – overnight – which is very unusual. She had clearly done that intentionally to break my ability to give some logic to the event. So I understood this as a secondary layer of oppression the state is applying to pro-Palestine activists.

How do you recreate that in a film? One way, of course, which is very common in trials, is that, as I’m playing the prosecution, I just interrupt. But the other is that we interrupt the creation of cinematic narrative. Narrative in cinema has this tendency… it’s like the Hitchcock quote: ‘Film is real life with all the boring bits taken out.’ There’s almost a demand for cinematic narrative to be logical, linear, deterministic. The demand is that you write a narrative in which, at the peak of act three, you reach a conclusion that’s quite satisfying. But we’re living in a world where there’s no more logic, right? Genocide is one of the most inconceivable, illogical things. What I’m seeing today are probably the most bewildering scenes I’ve ever seen in my life. I cannot fathom this level of cruelty and sadism. So why should I make a film in which logic applies, in which A leads to B in a way that’s predictable?

For some of the participants, there were breaks [in their trials] that are difficult to represent in a film. Film is always an act of translation, we just needed to find a material way of doing it. This is what I love about film, that we can talk intellectually about it for years but, at some point, if we’re speaking historically, there was a camera with film in it and there was a photochemical reaction. So you always have to figure out how you physically translate this sense of, let’s say, broken mental continuity, and make it physical. And so, for me, it was always about breaking the technical perfection of film, because the project in general is a comment on the construction of truth in cinema. We wanted to break that constantly.

LM: Does that influence how the set was designed? It has the shape of a courtroom, but it’s lacking all of the details. It’s plywood and hessian.

SF: We wanted it to be rough. First, it was based around people’s ideas and memories, so it’s not supposed to be a perfect recreation. There were elements of participants’ experiences that we had incorporated, whether in look, in size, in texture, or colour. The whole thing is like a memory. There was no script for them to memorise, for example. We would come up with a scenario, but then we would only really run through it just before filming, because nobody wanted it to be acting. We didn’t want it to be a performance. There always has to be something missing or something incomplete, or something slightly rough or unstable about it. For me, the most exciting thing about film is that you can bring the instability you get through live performance into the filmmaking process.

Eleanor Lu: I want to ask more about space and architecture. This project is a part of the militant architecture group AK48. Last year at Open City, you did a spatial performance lecture. In the past, your works were mainly filmed on-site and set construction was less of a focus. You seem to be moving further away from conventional filmmaking, and towards the creation of space and, through that, the building of bonds and communication between people. Could you talk a bit more about this newly founded collective and how that shift in your filmmaking practice came about?

SF: I think the simplest answer is that it’s an act of desperation. I can’t go on making long-term projects that are about symbolism, or sort of arthouse, gentle films when there’s a genocide against my people, and this government is complicit. I was in the middle of developing another fiction film and I lost patience with the process. We were also getting rejections that were clearly politically motivated, so it was so disheartening that I just put it aside and moved onto this very quickly, because I really needed something to put all of our rage, our desperation and our fears into – but also our desire to laugh together, and to be surrounded by people that I trust and love. So that’s the main reason why I’ve moved into this different mode.

I’ve always loved the kind of work that we’ve made, and the way that people work forces people to act in a way that maybe they’re surprised by. I mean, I think in particular about Tania Bruguera, a Cuban artist who does audience participation installations. There’s a piece of hers that I saw in 2008, I think. In it, the visitor walks into a room that’s completely black and you can hear people walking on a platform above you, and then, every once in a while, this bright light comes on, almost like a flash, and you hear guns being loaded. And that’s it. It just goes on like that; the guns never fire. But I just remember walking in, and this is when I wasn’t deeply into any kind of conceptual art, but I was so affected by it. I was terrified by that sound, first of all, but so excited by the fact that a piece of art could make me feel like that and make all of us feel like that, because there were also strangers in the room with me. And then she did a piece at the Tate Modern called Tatlin’s Whisper, where she got police horses and policemen to do some of their crowd control exercises for the people sitting in the Turbine Hall. She said what she found most surprising about it was that almost everybody just did what the police told them to, even though it was clearly an art piece. There’s no risk of arrest, no risk of anything. But again, it’s pre-emptive acquiescence – just the image of a policeman on a horse raises fear. So we do what we’re told, even though we shouldn’t. Those two works really blew my mind, in the way that something so simple can teach us so much about ourselves and how you can also have a bit of fun, because, at least with Tatlin’s Whisper, it’s sort of silly, the conditions are quite strange. I’ve always been interested in bringing that kind of performance and level of emotional intensity to film, but it’s only now that I’ve become more comfortable with doing things live, with aspects of performance. It comes with spending a lot more time with friends who do theatre and music and dance rather than just film. A lot of those elements are incorporated.

With the architecture collective, we’re still trying to decide on a name, but the idea came about like this: there’s a lot of academic research into oppression, oppressive architecture, and particularly the architecture of the occupation of Palestine. There are groups that reflect that academic approach, so they’ve done the analysis. Then, of course, there’s the architecture of occupation itself. What there isn’t is architects who are building resistance. So, in other words, if architecture and urban planning more generally is used to control us, and even used explicitly to crush liberation movements, how do we do the opposite? By which I mean, how do we build something that interrupts that system, or an architecture that might also be a form of resistance or a form of liberation? The inspiration came from the fact that, in Palestine, at least by Israeli law, if something is built with permanent materials, like brick, you need a court order to remove it. Whereas if something is temporary, like a trailer, the police can just come in and take it away. So, very often, when Palestinians are defending their land from settlers, they will creep in overnight and, under the cover of darkness, very quickly build a room with brick so that it becomes a permanent structure. So I thought, okay, this is architecture that’s directly challenging the occupation. How do we do that here? That’s kind of at the heart of the idea of this collective.

EL: So that’s why you invited people to build the set together?

SF: Yeah. Because we’re taking the architecture of the police interview room and the courtroom and turning it into an act of liberation rather than an act of oppression. That’s also why the day in between the two sets was probably, at least emotionally, the most important day, because we were taking everything apart. The participants built this police interview room together, they did their scenes, and then they got to tear the whole thing apart. That’s very powerful. The last day was the most cathartic because we got to take the whole thing apart for a second and last time, turning it into pieces of wood and delivering it to a friend who’s going to build something else with it.

EL: I want to pick up on how the idea of architecture you’re talking about isn’t just physical, it’s mental. When you’re inside a courtroom, how the whole setting might make you feel like you have to act a certain way. While you were filming, you had a script, but you would revise it after each take, consulting with the participants. Is that also a manner of regaining control over the process?

SF: Yeah, I mean it’s not really a script, it’s a kind of outline of the scenario. But this is something I learned from Kanafani Karaoke. That was where we took this very famous interview with Ghassan Kanafani, who was the spokesman for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and people signed up as though it was karaoke, playing the part of him in this kind of reproduction of the interview. Then they’d switch and play the part of the interviewer, and the next person would come in. So it’s also about creating these new friendships, right? Because we might be sitting across the table, we don’t know each other, but suddenly we act out a scene together.

Particularly in a country like Britain, explicit, radical political talk is very discouraged. I was shocked, for example, by people being interviewed on the BBC and saying something very straightforward – that Israel is an apartheid state, saying it with force, or saying with conviction – and then seeing how nervous the journalists get. The journalist has to say, ‘Well, hold on a minute, that’s a very contentious term, and I have to add that Israel will challenge the use of that term.’ This is not a country that respects direct, radical political speech. So that means most people are extremely uncomfortable asserting themselves in that way. And, because of the political climate, most people are very uncomfortable saying the word ‘resistance’ right now. Of course, for good reason, because you could be arrested, right? They’re uncomfortable saying the word ‘genocide’, because we’ve been told over and over again for the past 18 months that it’s a terrible word, that it’s extremely offensive. So the outcome of this project was people rehearsing the use of political language, which is important. You’ll need it if you’re arrested, or if you go to court, or if you’re having a conversation with your friends, or if you’re showing support for your friends who are in jail and you’re doing a speech in front of a prison. Whatever the case may be, we need to practice that speech. So what we’re doing by repeating a scene over and over again in the courtroom is also practicing those forms of resistance, so that when somebody says to you, ‘But what right do you have to sabotage a factory? There are ordinary working people there who might lose their jobs’, instead of feeling defensive, you know exactly what you’re going to say, and you say it with conviction. You know, I think the whole era of trying to convince people nicely is over, at least for me. And I think that’s an important break in this culture. It’s a very important moment where suddenly we as a political movement care less about convincing the masses that we’re right and more about simply doing the resistance ourselves. But, for a lot of people, that takes rehearsing, takes practice.

LM: Does that come into your practice as an educator? Setting up something like the Radical Film School, which is a space where people can practice making films in a radically political way. You’ve created a structure in which people can learn how to do that and become comfortable doing it.

SF: I think Radical Film School is adjacent to that concept of practice or rehearsal; it’s about exploring the things that keep us from speaking our minds or speaking honestly about politics. I mean, there’s this very English concept of propriety where it’s considered rude to talk about politics. Okay, but you know, it’s also rude to commit genocide. In many ways, the state relies on this. You’re constantly made to think you’re on your own. In other words, you may be fully confident of your political position, but you’re told you’re a tiny minority of radicals, and most of the country thinks you’re abhorrent, that your behaviour in general, in terms of mainstream society in England, is exceptional. This is not what most people believe. You’re constantly made to believe that. So, one of the outcomes and benefits of this kind of project, or Radical Film School, is people who have been made to believe that their entire lives are now in a room with 16 other people who see the world the same way they do. That kind of action, direct action, is not a mass movement. It doesn’t need hundreds or thousands of people on the street, but it does need at least a small and very committed, very trusting group of people. When you have that moment where you look around and see you’re in a room full of people who also see the world that way, and who understand that this is right, even if the state is telling you it’s wrong, that’s a very powerful moment of realisation.

It’s also about confidence in the way you express yourself through your work, but the other thing it does is demonstrate that you can start to create your own institutions, because the idea that you’re alone is also the idea that there’s no home for you or your work. And that may be true. We were talking about neoliberalism – certainly there’s the neoliberalisation of the art world and venues have absolutely betrayed the basic principles of an art venue by saying a piece of funding is more important than opposing a genocide, which I find deeply offensive. So now four or five students come together, they run their own art venue, and that becomes a place where you can show the work.

All of these things have to have a practical framework around them, and that’s why, when you put people together and they start to plan, they can implement that sort of practical framework for resistance in different ways. Like I mentioned before, if I know that you’re going to be there when I’m released from jail, I’m going to feel a lot safer about confronting the state.

EL: Where does this pull towards architecture come from?

SF: I don’t know why I gravitated towards it. I mean, I love architecture. I’m fascinated by it. For some reason that I’ve never understood, I’ve had very profound experiences with buildings. And I’m also extremely sensitive about architecture, in the sense that a space can make me feel very uncomfortable – one tiny change can make me feel awkward or uncomfortable. When I enter a building, I’m immediately reading it and trying to understand what my relationship to it is. Do I like it? What do I like about it? Is it telling me where to go, or is it letting me find my own way? I’ve sometimes wondered if it’s because I have an incredibly bad sense of direction and spatial awareness. So I become fascinated by how people manufacture spatial awareness. There are buildings that I can read and there are buildings that I can’t read, and when I can’t read them, it’s extremely frustrating, because I get lost. When I have nightmares, they’re very often about being lost in a building, or a kind of Dario Argento thing where there are hidden rooms, or a building like the Overlook Hotel where the architecture doesn’t make sense. Then suddenly I think: okay, well, what if I were to build a space? How would I do it? How would I challenge all of these discomforts?

LM: There’s quite a strong affinity between filmmaking and architecture anyway, right? Because both forms centre so much around constructing space. You say you wonder what it would be like if you were to build a space, construct relationships between spaces, but you’re already doing it.

SF: You’re absolutely right. I have a sort of theory, or a framework, that I call architectural cinema. It’s kind of the flip side of Pascal Schöning’s Cinematic Architecture. He was writing about how cinema has influenced architecture, but I’m more interested in how cinema is a form of architecture, and how, exactly as you said, filmmakers are designing space and the relationship between spaces. Even something as basic as the idea that the plot of a film is also a plot of land: it’s an empty space that has potential, but it also has limitations. It’s not completely open. So it’s one of these things where, every time I find a filmmaker who studied architecture – and there’s quite a few of them – I suddenly notice all these patterns emerging.

EL: Coming back to The Land of Common Disgrace, how do you imagine the presentation of the completed project?

SF: I think I’d like to tour it, particularly the parts of it we filmed here at Open City. I think it’d be really interesting to go to cities in the UK where there are Israeli weapons factories and where a lot of people have been arrested for protesting. So, essentially, we would enact the same process, though without necessarily filming it. It would just be a sort of public intervention, bringing these idealised versions of the trial and the police interview into the public. For me, that’s a really exciting, quite renegade form of public theatre, confronting people with these really radical principles. Again, if I had just my activist hat on, I think what’s really important is to show people that all of these heroes of the resistance are ordinary people: there are students, there are mothers, there are pensioners, there are teachers, there are doctors, and all of them have reached a point where they can’t take it any longer, and they’re willing to get arrested for it. These are ordinary people in Manchester, in Liverpool, in Bristol. Some of them have already served time in prison, and they’re fine. It’s not a great experience, but it’s not the end of their lives.

LM: It comes back to what you were saying about Third Cinema.

SF: I think a lot about whether cinemas will survive, and if so, how? How can we help them survive? One of the ways, for me, is to turn the cinema into not just a space where you go to watch a film, but a space for a lot more, whether it’s performance or participating in something. I’m also interested in the potential for just a cinema screening, even, to be a space for organising revolution.

On a very practical level, people are busy. There’s no way you’d get 200 people in a room if I said: let’s talk about direct action. But if you came to see a film, you’d get 200 people in a room, and if they’re all interested in the subject of the film, now suddenly I can say: if you want to come talk to me about direct action, do that. After every film screening, it might be two or three people, and then six months later, I see one of them smiling on TV, getting arrested. That’s Third Cinema. That’s revolutionary cinema.

A lot of it is about confronting fear, because so much of the state’s power is in our willingness to relinquish any sense of resistance. The state expects that once you’ve been on trial and maybe served time in prison, you’re now afraid. But you’re going out in public and saying: this is what happened. There’s also a fiction to it, which gives it a level of protection. That’s one of the reasons I like things like karaoke as a militant form. If I had invited people to a reading of Ghassan Kanafani, due to proscription, we might have been raided by the police. But, if I call it karaoke, suddenly nobody cares. I’m realising that what I like about these projects, – the kind of silly part of it, because we need a bit of that – is actually offering a layer of protection. But with the recreations, what we’re saying over and over again to the British public is, ‘I’m not afraid. This is what I did. And in fact, I’m proud of it – not just not afraid, but proud of it’.

This interview was conducted during Open City Documentary Festival 2025 in the framework of the Critics Workshop with Another Gaze.